I'm Jo Erickson, a producer with Colorado Public Radio. I came to Colorado this past summer from Minneapolis, where I covered several police shootings.

When a Black man is killed by the police, there's an outpouring of grief and then public outrage. The list of Black men fatally shot during police encounters keeps growing. Sadly the solution doesn't seem to be on the horizon. Research from the Mapping Police project shows that Black men are disproportionately killed at three times the rate of white Americans. But I don’t need to tell Black folks that.

Unfortunately African Americans know this pain and trauma all too well.

In creating Systemic, I wanted to tell the story of people taking matters into their own hands in hopes of changing law enforcement forever.

I asked Black officers, activists and people who've lost loved ones to police violence to record their parts in this history. Though their methods and ideas are different, they share a common goal: To change the system and to stop Black people from dying at the hands of police.

Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Pocket Casts

⬇️ SCROLL DOWN

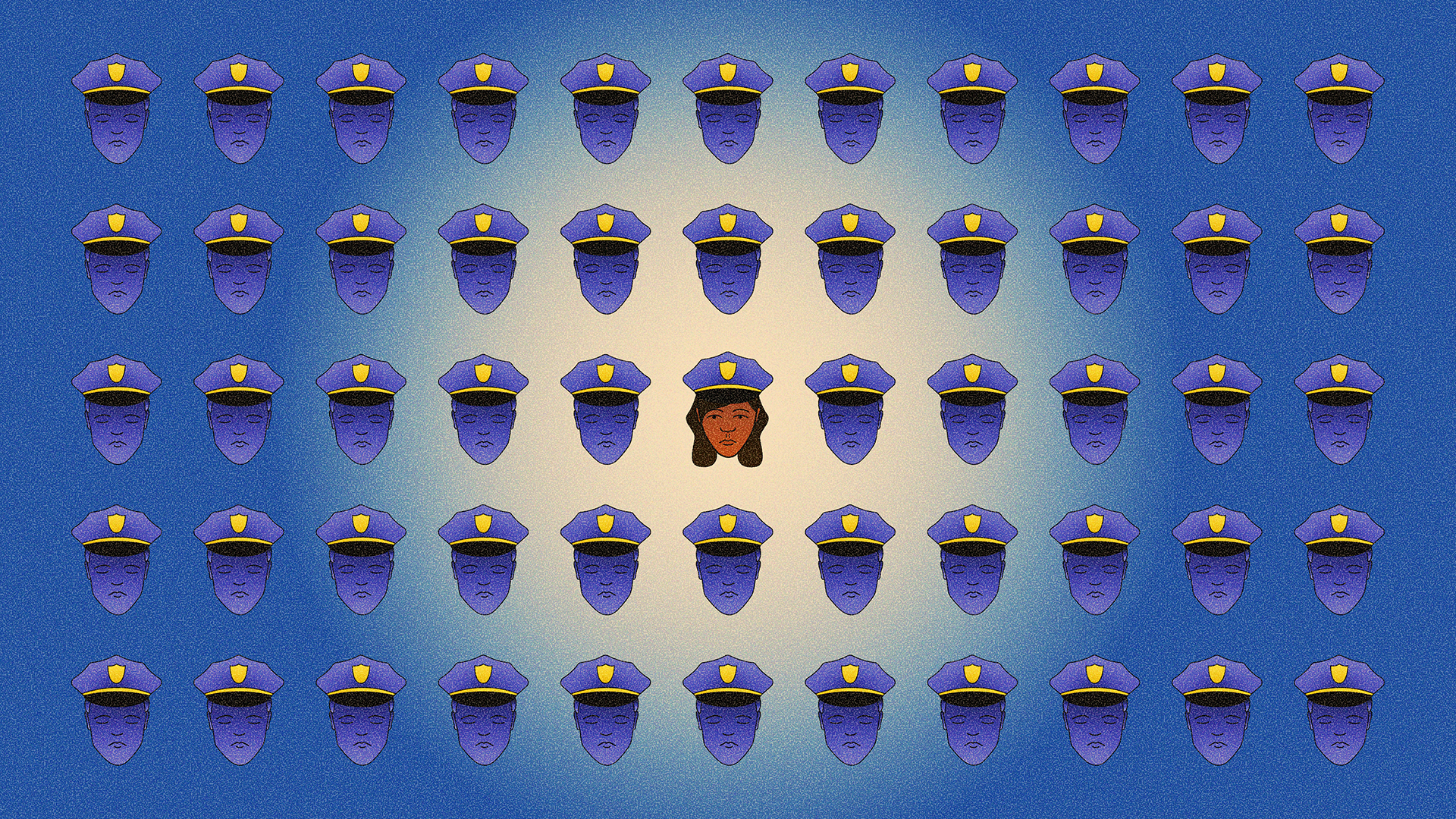

Episode 1: Black and blue

Rae Brown, 29, is a police rookie. She’s recently started as a patrol officer with the Maplewood Police Dept., in a suburb of Minneapolis/Saint Paul.

This is not far from where Philando Castile was pulled over in 2016 for a busted taillight — and fatally shot by police from another nearby suburb.

“I think that’s what sent me over with wanting to be a police officer,” she says, referring to the killing of Castile. She believed she could make a difference and save a life.

“I wanted to use this role as an opportunity to help kind of answer some of the questions that I had and potentially answer some of the questions that I know my peers and things have as well.”

Being a Black officer is difficult. They are often accused of having divided loyalties, where they must choose between being Black or blue.

But Black officers see their culture and different life experiences as a positive step toward a more inclusive police culture, where communities of color can begin to rebuild their trust in policing.

With just a little imagination, you could attribute this quote to almost anyone between about March 2020 and January 2021:

“Literally, in the back of my mind, I just think that this world is just so unfair and there’s no justice, there’s no equality, and just… some people get to do anything they want without any consequences.”

In this case, it happens to be something said by Michelle Reed, a deputy sheriff with the El Paso County Sheriff's Office.

A 10-year veteran, Reed voiced that thought into a recorder borrowed from Colorado Public Radio on January 7, 2021, the day after pro-Trump extremists stormed the U.S. Capitol in Washington, D.C.

Reed is one of several Black law enforcement professionals who spoke to me about changing the system to stop Black people from dying at the hands of police.

And about what it’s like to be a Black officer in a world still awaiting that change.

“I’m just a little concerned about what’s going to happen when I go out into the rural areas of eastern El Paso County where I’ve been seeing the Trump flags still waving in everybody’s yard, still hanging on the mailboxes, flying on the fences. And I just… I don’t know what’s going to happen, I don’t know how people are going to respond to me being out there.”

Photo: Iris Butler attempts to lead chants among supporters of Joe Biden as state police stand between them and supporters of Donald Trump at the Colorado State Capitol. Nov. 7, 2020.

Being a Black officer has never not been complicated. They are often accused of having divided loyalties, where they must choose between being Black or blue. But why should they choose?

Rae Brown saw herself as a person who could stop deadly incidents from escalating. Four months into her new career, she responded to her first 911 call of shots fired. It gave her a new perspective on what it feels like to make decisions when lives — her own and others — are on the line.

“Is there one shooter? Are there multiple shooters? Is there, you know, victims — it’s a mall. Is it an active shooter situation?

“Am I gonna end up in the news today? Am I not gonna end up coming home today?

“It’s so … I’m still jittery, you can probably hear it in my voice. I can still feel my heartbeat kind of racing a little bit.”

When police receive a 911 dispatch call with reports of shots fired, there are so many unknowns. But could Black officers help defuse these tense situations? Could the strained relationship between police and the Black community improve if there were more Black cops patrolling predominantly Black neighborhoods?

Listen to episode 1 on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Pocket Casts or online.

Episode 2: Survivor

In August 2019, Lawrence Stoker watched Colorado Springs police officers kill his 19-year-old cousin, De'Von Bailey.

Stoker is not short on reminders of the fear and grief of that day.

His daughter is the same age as De'Von’s daughter — De'Von didn’t live to meet either.

“Before he died, we would talk about our kids,” Stoker says.

Friends and families of Black men who’ve been killed by police say such reminders come to them indirectly in many ways, whether it’s the act of going for a run, as Ahmaud Arbery had done when he was chased and killed, or going to a convenience store, going for a walk, wearing a hoodie.

But for Stoker, there’s also this: From time to time, he runs into the same southeast Colorado Springs officers who arrested him the day they shot his cousin, in the same neighborhood.

“And sometimes me and the officer run into each other and he'll be like, ‘What’s up, Lawrence, how you doing?’ and I’ll put my head down.”

In Colorado, police are given the right to shoot a suspect to prevent them from escaping custody, if they “reasonably believe” the suspect used a deadly weapon or threatened to use one during a crime.

It’s called “the fleeing felon” law. And there's a gray area when police respond to a false report. But it’s this law that a grand jury cited in refusing to indict the officer.

Lawrence used this experience to motivate his friend Charles Chauncey to rally people to protest the police. And a few weeks after De'Von was killed, protests grew after another police involved death in Colorado — that of Elijah McClain.

The pressure from these protests didn’t go unnoticed.

“When I found out really what happened to De’Von Bailey, someone who grew up in the same community that I did, and how his life didn't matter to those law enforcement officers that were chasing him, that was hugely problematic for me,” says Colorado State Rep. Leslie Herod of Denver.

Together with other legislators, Herod started thinking how they could create change in policing. The ideas they discussed would become the foundation for Senate Bill 217. Its focus was to address key issues in police restraints, choke holds and to put an emphasis on police accountability. Police misconduct would lead to criminal charges.

“But I gotta be honest with you,” Herod says. “We didn't have the political will to get it even introduced much less out of the committee and pass both chambers.”

Soon, the whole world started to change. In March 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic suspended Colorado’s legislative session, leaving any new laws in limbo. And then, on May 25, George Floyd was killed by a white officer. And Black Lives Matter protests swept the nation.

“After the De'Von thing happened, the George Floyd stuff came up,” Stoker says. “Me, Charles Chauncey and our mentors made a group with more people that could get into City Hall.”

They were hardly alone in seizing the moment.

“In those first few days of protest,” Herod says, “we heard a clear referendum from all four corners of the state of Colorado that we needed to act and create change.

“It wasn't until the murder of George Floyd that we really saw people take to the streets and demand change. It was the people of Colorado that said no more. We want law enforcement to be held accountable and we want our lawmakers to lead that charge.”

Less than a month after George Floyd’s death, Senate Bill 217 was signed into law.

Lawrence’s work in helping pass the bill is seen by many as a huge step forward and a momentous achievement. But he viewed it as failure.

Regardless of the fleeing felon Law, the officer who shot and killed De'Von Bailey was also protected from prosecution, because the police believed De’Von posed an imminent threat to life.

For Lawrence, as long as this system stands, people remain unprotected from police violence. And it’s sent Lawrence into a deep depression.

Listen to episode 2 on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Pocket Casts or online.

Photo: State Rep. Leslie Herod of Denver, with her fist in the air, joined by Colorado Senate President Leroy Garcia of Pueblo, in blue mask, announces proposed police accountability legislation to protesters on the steps of the State Capitol Tuesday, June 2, 2020.

Episode 3: Hard Truths

Quovella Spruill is the first Black person appointed to be Director of Police and Public Safety for Franklin Township, New Jersey. She used her phone to record and share with us her thoughts on how she might make better police officers and how she might improve police culture.

It’s very concretely on her mind in October 2020. She's about to transform a mostly white male police department into something that represents the people she serves. After an exhausting day, she thinks about how her changes will be perceived. It's 1 a.m.

She’s hiring eight new officers, six of whom are Black. She’s worried that they might go through “trials and tribulations by being different,” but she’s hopeful that a more diverse department will be a better department.

“They are definitely going to change the dynamics around the department in terms of diversity and definitely inclusion.”

Like a lot of Americans, Spruill noticed a stark difference between policing of Black Lives Matter protests and policing at the U.S. Capitol, when mostly white extremists rioted and stormed into the building, where lawmakers and others hid and barricaded doors, worried for their lives.

She says she blames leadership, but that what she saw of the law enforcement presence in Washington that day was disappointing.

“I think it outright displays what our country believes, that they have to be more prepared, tactically prepared, for us versus other groups.”

The places where police culture and Black America meet need work. She has opportunities to make direct impacts — by educating fellow law enforcement officials, for example, on why using dogs to intimidate protesters has echoes of the use of dogs to torture and kill enslaved people who'd defied their captors.

But she also thinks that maybe America’s expectations of police should change.

Officers spend their time responding to pressing crises — overdoses, homelessness, and mental health emergencies, to name a few. At the same time, national police data show less than 1 percent of 911 calls are for serious violent crimes.

“It's too much,” she says. “It's a lot. Police have become social services. So police have responded to issues where, you know, children have not eaten. That's a call that we then have to make to social services, but guess who's there first.”

“You'll never eliminate police because you're always going to need someone to respond for certain types of emergencies and things that happen, but increased social services? Absolutely. And if a byproduct of that is to reduce the number of cops that are needed, so be it.”

Listen to episode 3 on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Pocket Casts or online.

Photo: Jerry Aguirre pays respects to George Floyd by visiting his mural on Colfax Ave. in Denver on Tuesday, April 20, 2021. Earlier that day, Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin was found guilty on three counts of murder in the 2020 killing of George Floyd.

Episode 4: Dismantle

Nekima Levy Armstrong spent the last seven years campaigning for police reform. In fact, law enforcement made her who she is today — she switched careers in 2014 after being tear gassed and witnessing police brutality during the protests in Ferguson, Missouri, that followed the death of Michael Brown.

Since then, she’s worked with Black Lives Matter and other groups to push police reform in her home city of Minneapolis. Her activism led to the fight for justice for Jamar Clark, Philando Castille, and Michael Brown.

Armstrong worries that the national conversation has focused too narrowly on the idea of a rogue officer, a bad apple, who is the exception rather than the rule. She believes that change needs to start with hiring officers who live in the communities they serve.

“It is going to take intentional effort, strong disciplinary policies, a shift in hiring, including no longer hiring officers who live outside of city limits, because right now, 92 percent of Minneapolis officers don't even live in the city of Minneapolis, including Derek Chauvin.”

Minnesota enacted some police reforms. Gov. Tim Walz signed a ban on neck restraints and chokeholds into law in July 2020 as a part of The Minnesota Police Accountability Act.

But in Minneapolis, people like Armstrong are not seeing change, despite promises from the city council.

“They came out in full force, nine of them in June of 2020,” Armstrong says, “and declared they were going to dismantle the Minneapolis police department. And they said this in front of a crowd of mostly white people out at Powderhorn Park without having consulted the Black community or done any kind of research whatsoever.”

When the city council did ask for input from the community, Armstrong and others brought forward ambitious ideas for how they could weed out problems in the police department.

“One of the elders in our community suggested that every Minneapolis police officer should have to reapply for their jobs. That to me is an outstanding solution because it means that you would look at their record of service and complaints, their temperament, and make a decision about how they will add or detract from the culture and whether they deserve to control the streets of Minneapolis.”

Photo: Khyra Parker raises her fist during nine minutes of silence during the sixth day of protests in Denver in reaction to the killing of George Floyd by Minneapolis police. June 2, 2020.

When I first started this project I was swept along with the enthusiasm of this moment, a time where change looked possible. A year on, there are still new cases of police shootings of Black people.

Throughout this series I’ve seen how people are making changes around the country on police reform. Black officers pushing to change police culture, and activists demanding less policing and more targeted resources for crises. But changing the system is hard.

And when you can’t change the system, do you allow the system to change you, or does something else happen?

Before releasing this project, I reached out to the people we’ve featured to see if their views have shifted. Not surprisingly, most of them had not. But Rae Brown, the Minnesota rookie officer from episode one, told me she was reflecting differently on her career path.

And she recorded one last message:

Listen to episode 4 on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Pocket Casts or online.

Photo: Denver protests in early June against racism and police brutality after George Floyd’s death at the hands of Minneapolis police.

? To learn more about how and why we produced a podcast about people working to reform policing from inside and outside the system, read this message from the team.

"Systemic" is brought to you by Colorado Public Radio's Audio Innovations Studio. Launched by philanthropic seed dollars, the Audio Innovations Studio is an incubator designed to drive a culture of innovation and experimentation within the public radio sphere. Help make more ground-breaking audio projects possible with a gift today.