Reporting contributed by Taylar Dawn Stagner

A pivotal place in the history of the Colorado River is down a narrow desert road in Northern Arizona. To get there, you have to drive through towering canyons of rust-colored rocks, and past herds of bighorn sheep. When the road finally reaches a parking lot near the river’s edge, you’ll see a wide expanse of clear water, some dilapidated stone buildings and people applying sunscreen.

This is Lee’s Ferry, a popular spot downstream from Lake Powell where people launch their boats for a journey through the Grand Canyon.

But the spot hasn’t always been a recreational destination. Indigenous people first used this place as an important river crossing. Then it was settled by Latter-Day Saints, who were some of the first white colonizers in this area. The group saw it as their mission to spread across the southwest, establishing farmland and communities and evangelizing their religion. They set up this spot as a river ferry, with a man named John Lee as the ferryman who moved people, supplies, livestock and anything else they needed across the water.

The move helped lay the groundwork for exponential growth in the southwest, allowing people from the eastern part of the U.S. to move west and set up cities and farms on arid lands. But those settlers violently pushed out native people who called these areas home, and then denied them access to the water they relied on. As climate change diminishes flows in the Colorado River, regional leaders are negotiating its future and Indigenous people want that to include establishing their full access to the water.

A river divided in two

Here at Lee’s Ferry, seven southwestern American states divided up the Colorado River with the 1922 river compact. Every single drop was spoken for, between Wyoming, Colorado, New Mexico, Utah, Nevada, Arizona, California, and later Mexico. The water was destined for colonized farmland and cities.

But crucially, that 1922 compact denied 30 different Indigenous tribes any share of the water that they needed to survive in the hot and dry southwest.

While the federal government helped states build pipes, dams and reservoirs to access the water they were allocated, it didn’t do the same for Indigenous reservations, and many people living on those reservations didn’t know what water they could use.

This was an abrupt departure from the way tribes had lived before white colonizers arrived in the West and forced the tribes onto reservations. For thousands of years, many Indigenous people moved with the river; they adapted to it and responded to it.

This is how Daryl Vigil’s ancestors lived in communion with the river.

“That's the level of reverence you give that stream or that river,” Vigil, a member of the Jicarilla Apache Nation and of Jemez and Zia Pueblo descent, said. “The dances all revolved around this cyclical nature of the environment and most importantly, rain and snow in terms of what it meant to our existence.”

But as the colonizers built gigantic dams and carved up the river, filling Lake Mead and Lake Powell, the Jicarilla Apache and dozens of other tribes that rely on the Colorado River no longer had the same access to the water as they once did.

This was the West that Vigil was born into and where he grew up on three different reservations – at times without indoor plumbing. He now lives on the Jicarilla Apache Reservation north of Santa Fe, New Mexico, and until recently was the tribe’s water administrator.

He is among the most recent generation of leaders in a decades-long fight for tribes to regain rights to the water they had access to for thousands of years.

“Part of the need to build economies is also based in an ability to build a basic infrastructure that everybody else in this country is supposed to be entitled to: water, wastewater,” he said. “Native American communities [are] 19 times more likely to not have indoor plumbing.”

When the Colorado River Compact was written in 1922, tribes were left without a legal say in how the river should be shared and managed across the west. But slowly, over the last 100 years, they have pushed for legislation, court cases and settlements — some of which dragged on for decades — to take back their rights to the river.

The Jicarilla Apache Nation started campaigning for water rights in the early 1970s, after rapid growth in the southwest began to drain the only perennial river that flows through Dulce, the town at the center of the reservation. It wasn’t until the 1990s that the tribe secured their share of the Colorado River.

The era of gigantic dams

As tribes were fighting for their rights to the water, and a seat at the bargaining table, the total amount of water to go around was evaporating. Climate change was working hand-in-hand with exponential population growth in the West to deplete the supply of water in the river.

“My message for 20 years now has been: watch out,” said Brad Udall from his home near Boulder, Colorado. “We've overdone it, we need to cut back and this is going to get worse. And that's not a message that, for years, anybody wanted to hear.”

Udall is senior water and climate research scientist and scholar at Colorado State University’s Colorado Water Center — a “delightful title,” he said. Udall studies the Colorado River and the climate change that’s impacting water levels. As part of his work, he often points out that the country’s largest dams, reservoirs and water projects will go dry if we continue using water as we are today.

But Udall doesn’t just study the Colorado River; he and his family are intimately connected with its history. John Lee, the man who ferried Latter-Day Saints across the river, is Udall’s great-great-grandfather. Lee and others in Udall’s family tree helped establish communities in parts of the country that some had deemed unlivable.

Their success led to more Americans moving out West, which meant they needed to use more of the river. They built homes and fields and raised cattle, and they needed their water to be reliable.

“The problem is, in the American southwest especially, you do not have reliable water supplies. You have very large changes from year to year and rainfall and snowfall, and you have little tiny rivers compared to the East Coast,” Udall said.

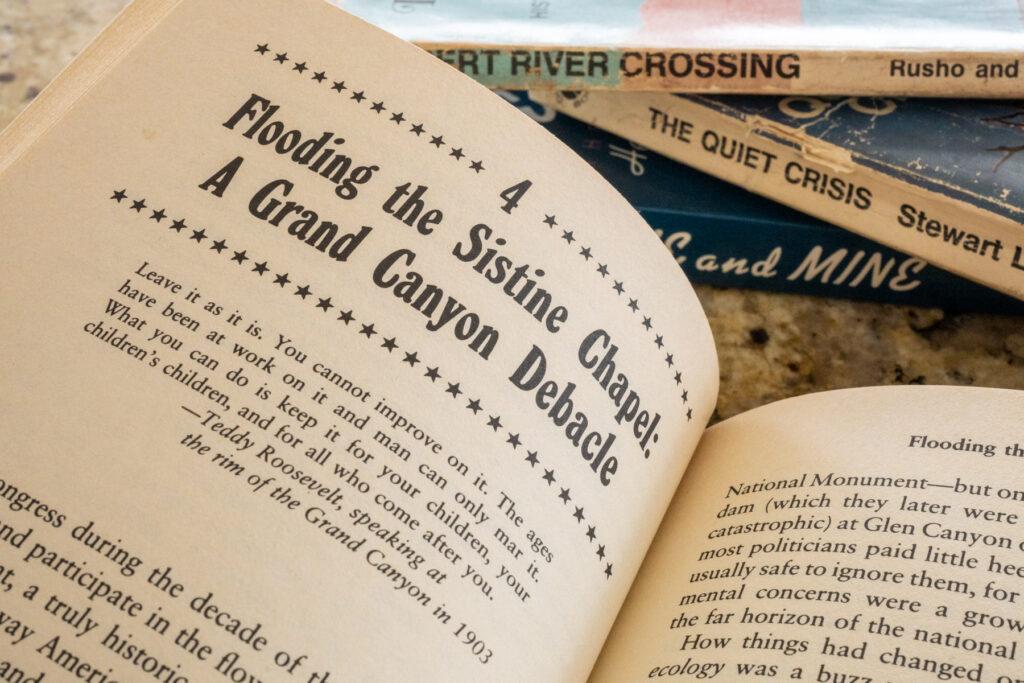

This is what ushered in the era of gigantic dams, and later generations of Udall’s family were key players in building those dams. His father, Morris Udall, a former Arizona congressman, and his uncle Stewart Udall, a former secretary of the Department of the Interior, were especially involved in the Central Arizona Project, which pumps Colorado River water hundreds of miles to cities like Phoenix and Tucson.

It’s these gigantic dams, reservoirs and canals that have allowed tens of millions of people to live and work in the southwest. They help grow millions of acres of food. They help provide drinking water to cities like Los Angeles.

Udall’s father and uncle saw how managing water with dams and reservoirs could lead to economic growth for some communities; they almost drowned one of America’s most iconic landscapes: the Grand Canyon.

“They had no idea what they were talking about, frankly,” Udall said. “They thought dams and water and canals were all good things. By their standards, they probably were, but they didn't know what they were dealing with.”

And while flooding the Grand Canyon seems like an outlandish idea, this is exactly what happened to create Lake Mead and Lake Powell — these were sacred canyonlands that were filled with water.

Today, as the reservoirs dry up, low lake levels are revealing burial sites, buildings and artifacts like pottery.

Thinking about the Colorado River as a resource was totally opposite to the way Indigenous people had lived around the river for generations.

“I laugh because those dam dreams … that was the thought: ‘We'll build these gargantuan facilities and we're going to tame nature. We're going to show how we're going to manage [the river,]’” Vigil said. “The arrogance of that thinking, and how it's tied to the general thinking of that time, in terms of how we were going to develop as a country.”

And, while those dams went up to create opportunities for some communities, tribes were cut off from water.

“What did that do to the other opportunities for Native Americans?” Vigil said. “We continued to be an afterthought and [they] hoped that maybe we would go away.”

A new blueprint for the reality we face today

Though Daryl Vigil and Brad Udall have very different histories with the Colorado River, they have both dedicated their lives to the same thing. The two men want a foundational blueprint for how we manage the river that is reimagined for the realities we face today.

Because the realities today are that we do have gigantic dams, which hold water in large reservoirs that tens of millions of people depend on. The water that flows into those reservoirs isn’t as abundant as it once was. And the states that govern the water supply still have excluded tribal voices from a primary seat at their bargaining table.

Remember the Colorado River water rights that took 20 years for the Jicarilla Apache Nation to win? They and other tribes have collectively secured rights to use 25 percent of the water in the river. That’s more than Arizona has rights to. But here’s the catch: reservoirs and canals the reservations need to access their full supplies of water don’t exist yet. Without that infrastructure, the water is still going to states, rather than the tribes.

This is why many people, including Vigil and Udall, want tribes to have an equal say in how we save the Colorado River in the face of climate change.

Vigil has dedicated the last 12 years of his life to getting decision-making power for Indigenous people. His hope is to get states and the federal government to legally include tribes in river decisions that will either make or break all of our futures in the West.

Speaking before a congressional committee in 2021, Vigil said, “It is my sincere hope that the attention and the action of this committee represents the beginning of a new chapter in the management of the Colorado River, a chapter in which tribes are treated with the same dignity and respect and responsibility as other sovereigns in the basin.”

And in 2022, Secretary of the Department of the Interior Deb Haaland promised more tribal inclusion, which makes Vigil feel hopeful. But until concrete plans are put in place, his and other tribal leaders’ fight for inclusion will continue.

“We can go back and we can beat up on it all we want to and blame urban development, or why did we choose to live in the desert? It doesn't matter,” said Vigil. “What matters right now, in terms of how we move forward, is an acceptance of reality [of] the hydrology that exists. And we need to talk about equity, and inclusion, and basic human justice as part of these conversations in terms of the allocation of this finite resource.”