Updated at 12:54 p.m. on Tuesday, May 28, 2024

Jacques Bailly was a Denver eighth grader when he won the Scripps National Spelling Bee in 1980.

The winning word (“elucubrate“) scored him a trip to the White House where, according to reports at the time, his name was misspelled in the program.

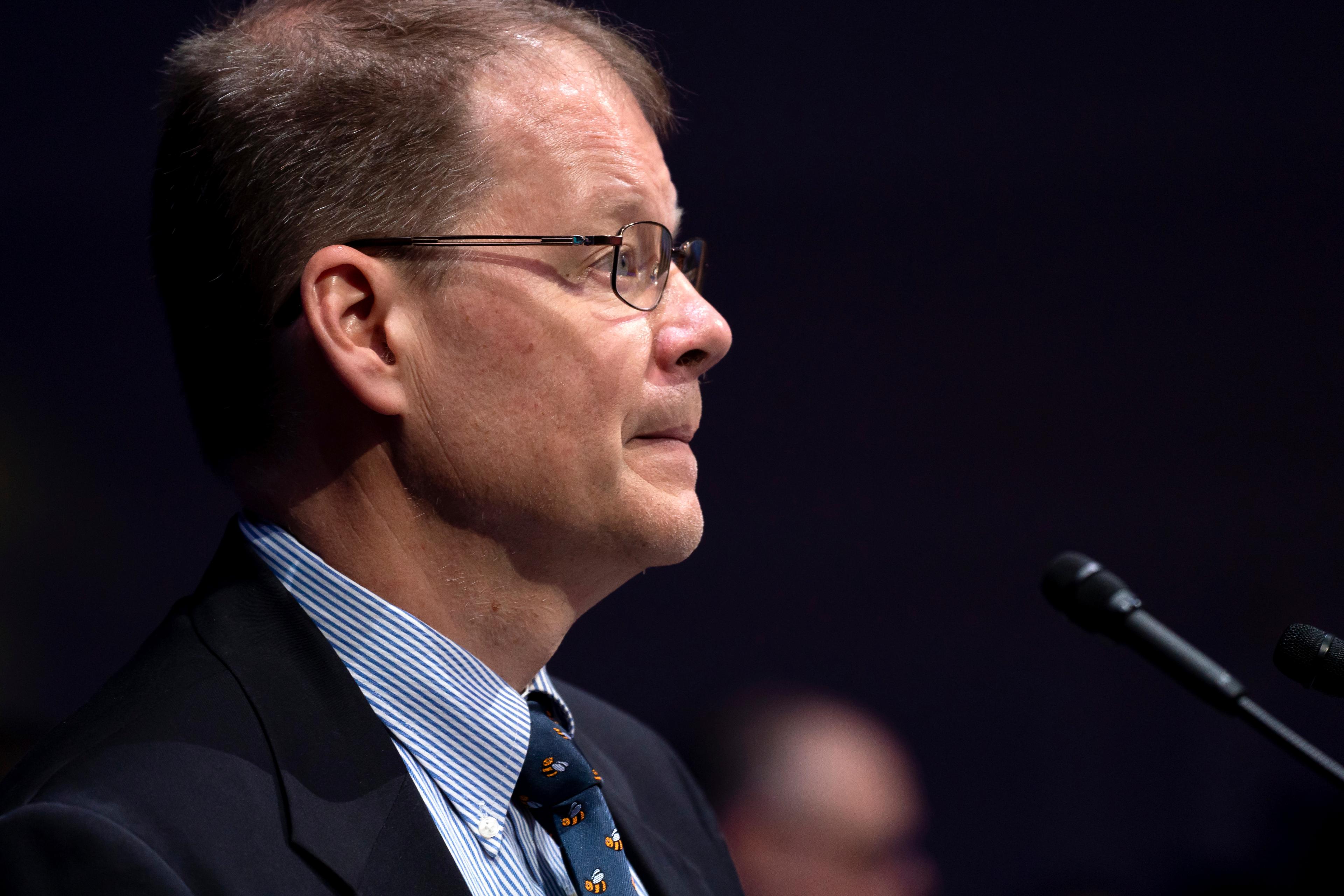

Today, fans of the annual teenage game show that puts Jeopardy to shame know Bailly as the bee’s pronouncer, a post he’s held for 21 years.

This year’s bee starts today and runs through Thursday, May 30. The winner will take home a $50,000 prize.

Colorado has two contestants, Aditi Muthukumar of Westminster and Cooper Edwards of Boulder.

The bee's mission, and breathing deep

“I'm basically in it because I think that the mission of the bee to incentivize kids to learn about their language and to use it better is my mission,” Bailly said. “I share that very strongly.”

For a few days every spring, competitors take their seats on stage and then march to the standing mic one by one. Bailly greets each by name.

“I just try and catch their eye and smile at them. And if they seem particularly nervous, I'll actually ask them to take a deep breath with me, and that often works,” he said.

They respond politely, inevitably addressing him as “Doctor Bailly,” because he’s a professor of the classics at the University of Vermont.

Spelling, giggling, fainting

And then it begins.

In precise tones, Bailly reads a word – like “bewusstseinslage,” for example.

One year it was “sardoodledom,” which sent contestant Kennyi Aouad of Indiana into uncontrollable fits of giggles.

“There is a performance aspect of it, and they have to keep their cool and be able to think in the spotlight,” Bailly said.

Things occasionally get overwhelming: In 2004, Akshay Buddiga of Colorado Springs keeled over from the strain. Within 20 seconds, he got up off the floor, returned to the mic and – correctly – spelled “alopecoid.”

For most kids, Bailly said, being on national TV seems to outweigh the pressure of the day. And even those who get a word wrong learn something in the end.

“We need to know how to stumble, we need to know how to get up after we stumble,” Bailly said. “Knowing how to do that in public, to do that gracefully, is supremely important. And this is a learning opportunity that I think is a really good one.”

Bailly spoke to Colorado Matters host Ryan Warner from his home in Vermont before leaving for this year’s spelling bee in National Harbor, Maryland. (He put Warner through a mini-bee.)

Read the I-N-T-E-R-V-I-E-W

This interview has been edited for clarity.

Ryan Warner: I guess we might as well start by having you pronounce and spell your winning word from when you were a kid.

Jacques Bailly: So my winning word back in 1980 was elucubrate, and it is spelled E-L-U-C-U-B-R-A-T-E.

Warner: Elucubrate?

Bailly: Yes.

Warner: Can I try to guess the meaning? I didn't look this up.

Bailly: Sure, it means the same thing as lucubrate

Warner: Elucubrate, I'm going to guess that it has something to do with speech and elocution. What do you think?

Bailly: Well, remotely. It means to study all night, to burn the midnight oil, to really go the extra mile in studying.

Warner: I'll note that the bee win got you a visit to the White House, where they spelled your name wrong in the program, is that right?

Bailly: I don't remember that detail. I was pretty excited to go to the White House and meet Jimmy Carter, and it was in the Rose Garden, it was wonderful.

Warner: So the spelling didn't stand out or the misspelling?

Bailly: So many people misspell my name, it's nothing unusual.

Warner: What keeps you coming back to the bee as a pronouncer?

Bailly: Oh, it's definitely the kids and education, and it's just so much fun. I'm basically in it because I think that the mission of the bee to incentivize kids to learn about their language and to use it better is my mission. I share that very strongly.

Warner: So the contestants walk up one by one to spell their words.

Bailly: Yes, there is a performance aspect of it, and they have to keep their cool and be able to think in the spotlight.

Warner: One of them this year is 8 years old, a live national broadcast with a studio audience, I wonder if you do anything to try to loosen them up.

Bailly: Well, it's pretty subtle. When they come up to the microphone, I have the sort of pronunciation of their name ready because the staff has asked all of them how to pronounce their names, and we've created a pronunciation guide. So I can greet them by name and then I just try and catch their eye and smile at them. And if they seem particularly nervous, I'll actually ask them to take a deep breath with me, and that often works.

Warner: It's subtle, but it's so kind. Can you tell right away before they spell if they know a word?

Bailly: You can't. By and large, you can kind of make an educated guess. But I've been surprised so many times when they've spelled a word correctly that there is no way you could spell it correctly without just knowing it, or they seem very confident and then they miss. And so I think that they have game faces, and there are things going through their minds that you can read on their face, but it's not always what you think it is.

Warner: Can you think of a word that a kid wouldn't be able to spell unless they knew it?

Bailly: Yes. There's a word, paixtle, it's a kind of dance, and I would challenge you to come anywhere near the spelling of it.

Warner: Okay. I'm going to do the things that kids can do in the competition – what is the language of origin?

Bailly: Just a second, let me pull up my dictionary so I don't give you any false information. I believe it's Quechua, but let me check that, it might be Nahuatl.

Warner: So it's an indigenous …

Bailly: So it went from Nahuatl to Spanish to English.

Warner: Okay, one more time. And I can ask you to pronounce it again if I were in the competition, right?

Bailly: You can ask me all these questions for about two minutes. I can't remember what the exact time limit is now, but it might be two minutes. So paixtle.

Warner: Okay, P-A-I-X-T-L-E.

Bailly: You knew that.

Warner: I did not know that.

Bailly: Really? How'd you get it? That's amazing.

Warner: Wait, is that really the spelling?

Bailly: It is, yes.

Warner: Oh, my gosh.

Bailly: You win the spelling bee.

Warner: And it's a kind of dance?

Bailly: Yes, it's a fiesta dance of Jalisco, Mexico.

Warner: People are going to think that we cheated, but I promise you ...

Bailly: I can give you another one.

Warner: Okay.

Bailly: This is a boat from Malta and the word is dghaisa.

Warner: Language of origin, please.

Bailly: Maltese.

Warner: Yeah, okay. What other questions can I ask about a word, anything else?

Bailly: You can ask me for alternate pronunciations, but this one has only one, dghaisa. And the definition — a small boat resembling a gondola that is common in Malta. A part of speech — it's a noun. And the use in a sentence — I hopped on a dghaisa on my tour in Malta.

Warner: You have to have all those facts ready.

Bailly: Yes, they come on a screen in front of me. And we have worked very hard for at least a year on this list. In some cases, the words have been in our data banks for longer, and we review them many times. So I'm just making this up on the spur of the moment, so it probably won't be quite as high quality.

Warner: Okay, D-Y-S-S-A.

Bailly: No.

Warner: The judgment, Jacques! How is it spelled?

Bailly: D-G-H-A-I-S-A

Warner: Wow, okay, there's no way that I would've guessed. How are the words chosen?

Bailly: So there are people we call word panelists, and they're publicly announced. We have Barrie Trinkle who is ... I think she's fully retired now. She used to work for Amazon years and years ago. She's a former winner of the national bee, and she is a wonderful reader. She reads a lot, and I think she chooses words in her reading.

We have somebody else who is a dictionary editor with Merriam-Webster, Peter Sokolowski, and I think he chooses words by looking in the dictionary during his work. We have Dr. Kevin Moch, he's often contributed words, and I think it's a mix with him. He is a font of knowledge about the bee, he was in the bee years ago.

Warner: I'm fascinated by how many people were in the bee and then take part in shaping it.

Bailly: Oh, people really ... They devote a very intense part of their young life to the bee, and they want to keep going. And so there are more people than we could possibly accommodate. I just got very, very lucky when I wrote to them in 1991 and said, “Could you use a volunteer?” that they actually could at that point.

Warner: After all these years, do you still learn words?

Bailly: I'm always learning words, because I can't remember them all. There are words that I learn every year that I didn't remember from last year. I'm not like these young kids, my mind used to be a lot better at this, I'm not that good of a speller anymore. And if I don't use words, I don't necessarily remember them.

But there's some weird words like pentacosadiynoic acid is kind of fun. And I use that as an illustration in my etymology class, so there are some words that I never use that I know. It's funny, we think the dictionary has all the words, it doesn't, it has nowhere near all the words. There are easily five to 10 times as many words in the English language as there are in the unabridged dictionary.

Warner: I mentioned you represented Colorado in 1980. How did you get...

Bailly: Yes, Colorado and Wyoming.

Warner: And Wyoming. Oh, we were a kind of super state at that time?

Bailly: Yes, exactly, it was a two-state competition.

Warner: How did you get your start in spelling?

Bailly: In the sixth grade Sister Eileen (Kelly) asked me after a few weeks in class when a bunch of us had taken some spelling tests in the normal course of our classes, she asked me and a few others if we wanted to be on the spelling team. And my brother was asked too, and that was just great. So we both did that together after school as an activity.

Warner: It occurs to me that in people's lives there are educators who come along, and they really put you on a course, they change the course of your life. I wonder if you feel that way.

Bailly: I think that's very true, and I think that there's a magical time between middle school and high school where the educator is most likely to be able to make a huge impact. Of course, I do remember my first, second and third grade teachers too. But yeah, I think you're right, teachers have an incredible impact.

Warner: How did you prepare for the National Spelling Bee at the time? And maybe contrast that with how kids prepare today.

Bailly: So I had two phases. For the first two years, I did mostly memorization with Sister Eileen, and then my mother would drill me on lists. And she assumed that when I was talking with Sister Eileen, I was learning about etymology, and foreign languages and such, and then she figured out that I wasn't. And so in my third year, she and I worked a lot on patterns of words in etymology, and figuring out that actually all these Hawaiian words aren't that hard.

So we made lists and lists of words. We studied all the words to begin with the zee sound, so some of them are with an X, some with an S, some with a Z. Trying to figure out different ways to approach words and get clues as to how they're spelled.

And I think that the kids who win nowadays do that same thing. There's a lot of memorization because there are words that are frankly sight words. If you haven't seen them, it's highly unlikely you'll spell them correctly.

Then there are words you can figure out, and you don't necessarily need to remember all those, like that word I mentioned, pentacosadiynoic acid is probably not that hard for these kids because it's made of parts that they know. And I'm talking about the stratospherically good spellers who are in the finals at the National Bee. When you're talking about your average eighth-grade speller, it's a fairly different picture. They're probably still learning things like, ‘Well, anytime you have an eff sound, you can ask, is it from Greek or Latin? If it's from Greek, it's probably a P-H.’

These kids at the finals in the bee, they know that there are exceptions to that, and they've tried to look up all those exceptions. So it's levels and levels. It helps an awful lot if you studied a foreign language, particularly French, Latin or Greek. I had studied a fair bit of French because my father was French, but Spanish helps, German helps. Chinese not so much, because they don't really spell their words, they use the characters. And then the transliteration is often fairly straightforward.

Warner: You mentioned Hawaiian.

Bailly: Hawaiian's an amazing language. They have very few phonemes, so they don't have that many sounds that make meaning. But their words sound very foreign to the average North American English speaker. You hear about their state fish, the humuhumunukunukuapua'a. And that's kind of exotic for most people. Of course, if you're from Hawaii, it's not, it's just the state fish.

Warner: I remember as a kid flying to Hawaii with my family, and a flight attendant said the name of the state fish over the loudspeaker. And as a lover of language, as a lover of words, I was just dazzled by that moment.

Bailly: Yeah, it's a great one because it has that reduplication twice, the humuhumu nukunuku. It's an amazing, wonderful word.

Warner: There's no minimum age to compete in the bee. Indeed, they range this year from eight to 15. I've got to imagine, and certainly you see this when you watch it, the pressure on these kids is enormous. And I wonder if it's fair to them, Jacques.

Bailly: I agree with you that there is some pressure, it's largely self-induced, and it's an energizing pressure. From all that I can gather getting to be on TV is a fantastic thing for them, when they realize they've made the cut, that they'll be on the finals on primetime TV, that in itself is a huge reward for them. So you might think of it as pressure and think that's really harsh, but they want that, that's what they're there for.

Honestly, I think that this performance aspect of the bee is something interesting to think about, because we need to know how to stumble, we need to know how to get up after we stumble. And knowing how to do that in public, to do that gracefully is supremely important. And this is a learning opportunity that I think is a really good one.

Warner: It occurs to me that it's a way to confront and maybe get over shame and embarrassment. And of course, the cash prize is not hurting anyone either.

Bailly: Oh, it's a huge cash prize, yeah. You're right, that I think what you have to realize about shame and embarrassment, is that when you miss at the National Spelling Bee, I would be very surprised if anybody would ever say, "Oh, my gosh, I can't believe you missed at the National Spelling Bee."

They will be so impressed that you are in the National Spelling Bee, and they will be impressed at this word, and they will want to know how to spell it, and it will be something that you can crow about rather than any problem.

Warner: I wonder if it's sometimes harder on parents.

Bailly: It is, I think it definitely is. That is true, you can watch their faces in the audience, very much so often you'll get the camera on them and it's excruciating. Or little sisters and little brothers, oh, they are so crushed sometimes when a speller misspells.

Warner: Oh, that's so sweet, siblings rooting for siblings. I'm also fascinated by how often siblings follow in the footsteps of siblings.

Bailly: I think it's because studying is often something that happens for a great deal of time in the household, and siblings of course know what each other are doing and often participate in the same activities. So the younger brother or younger sister will be learning those spelling words well before they enter the spelling bee. And also you need somebody to help ask you the words, and your mom and dad or your friends aren't always available, so I think siblings probably help with that too.

Warner: You of course have to be impartial, but do you get to meet the kids during the bee, spend any time with them?

Bailly: Yeah, so I do have to be impartial, but it really comes easy to me because I really don't care who wins. I am so proud of all of them, and feel like what they won is what they learned, and they're going to go home with that no matter what. I also do get to meet them, during the week they have activities, and I have to sign hundreds of autographs because they are my fan club, and I have the best fan club for one week a year. I'm their fan too, because I often get their autographs.

Warner: You've been called, by the way, a spellebrity. I love that.

Bailly: Oh, yeah, we have spellebrities and we take spellfies.

Warner: Spellfies for photos.

Bailly: Yes, spellfies.

Warner: Jacques, there are a few words that I have always had trouble spelling, rhythm.

Bailly: Oh, no, you're going to ask me to spell them.

Warner: No, no, but I'm going to ask if there are words that do that for you. I am always perplexed when I start to type rhythm or ... and sorry for the scatological nature of this, but diarrhea always throws me, the R's and H's.

Bailly: So the thing about all those words that come from Greek and have rrhea in them, like logorrhoea, is that they all have R-R-H. And it has to do with Greek, you can't have R-H, just R-H in the middle of a Greek word, it's always R-R-H I think.

Warner: Okay, even that is helpful. Are there words that have vexed you for a lifetime?

Bailly: All those pasta words like pappardelle, whether it's two L's or not, I always get confused. And some of them with the double T's, I always have to look those up. I think I know spaghetti by now, but...

Warner: Well, there's something comforting about all this. Break a leg, thank you so much for being with us.

Bailly: Thank you, Ryan.

Editor's Note: A previous version of this story misstated where spelling bee contestant Aditi Muthukumar is from.