Gov. Jared Polis signed yet another property tax law today. Coming on top of earlier cuts, it’s meant to be the final-ish word in a debate over taxes that has carried on for years now.

The new tax law is the result of last-minute negotiations and a special legislative session. By signing the law, Polis is ensuring that voters won’t get the chance to approve much deeper tax cuts this November.

As a result of the new law, a coalition of business and conservative leaders has withdrawn a pair of ballot measures, saying that the cuts passed by lawmakers are good enough. And they’ve promised not to run any more cutting measures for six years, as long as the legislature holds up its side of the bargain.

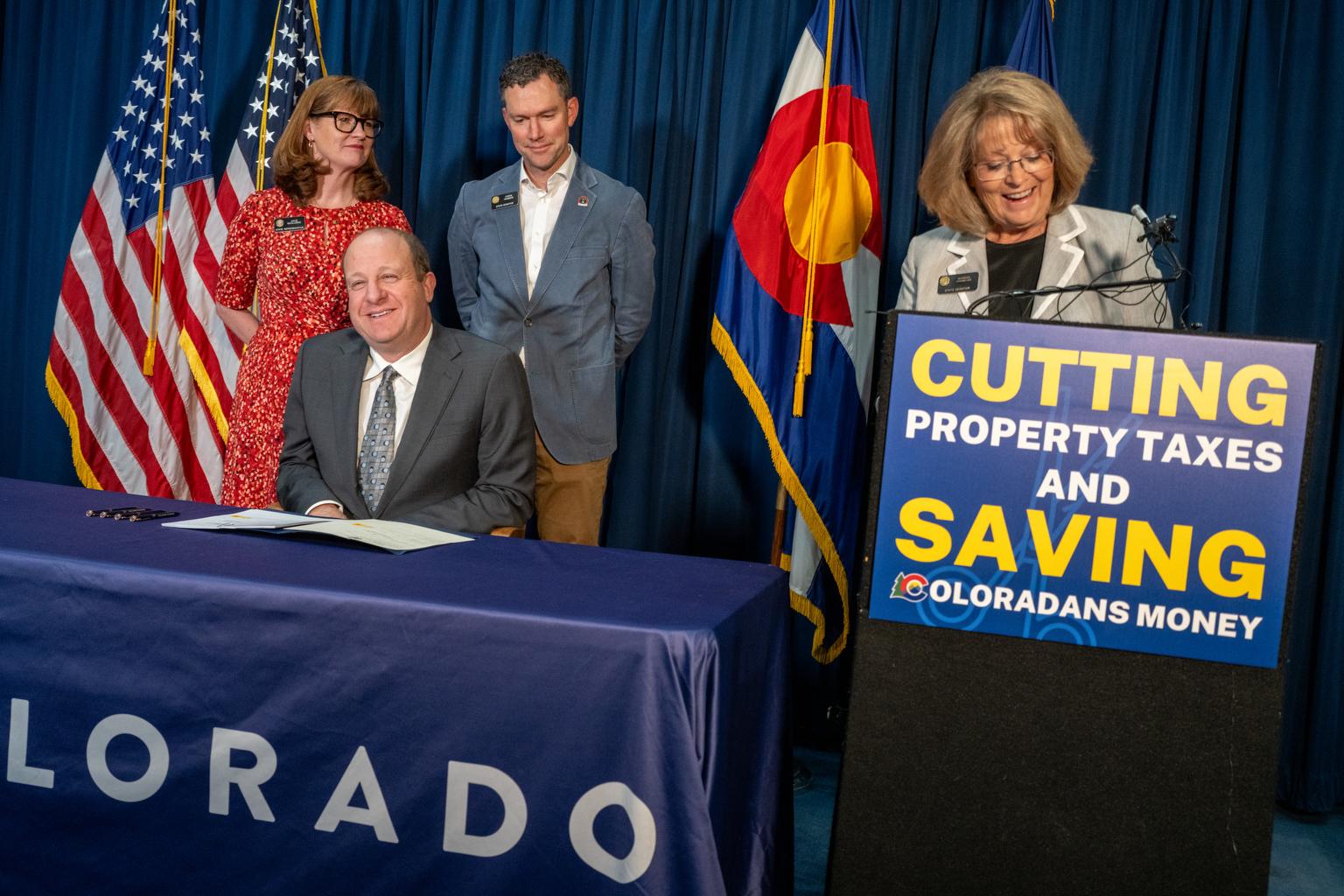

The compromise comes on top of earlier cuts that were passed in May as part of the same negotiations. As he signed the bipartisan law, Gov. Jared Polis declared an end to “the property tax wars.”

“This bill provides immediate as well as ongoing property tax relief for hardworking Coloradans by cutting the residential and commercial property tax rates and capping future increases,” he wrote in a letter.

So, what can home and business owners expect to get out of this package?

For homeowners: Savings compared to the status quo, but bills are still going up

The compromise measure permanently lowers one component of the property tax formula for homeowners.

Figuring out how much money homeowners will save, however, is all about perspective. Lawmakers have made so many tax changes in the last few years that it’s hard to know what to compare the new rates to.

One comparison would be to the “status quo” — what homeowners would have paid in coming years if no action were taken. Prior to all this negotiating and compromising, a home worth $650,000 in a typical taxing district would have owed about $3,850 in property taxes under the old tax rates for tax year 2025. (To make things more confusing, 2025 taxes are paid in calendar year 2026.)

Between the two rounds of compromises, that tax bill is lowered by nearly $300 once the new cuts are fully in effect. Most of that cut happened in May, although homeowners also got a little more trimmed off during the special session negotiations.

Altogether, that’s a savings of about 8 percent against the status quo, and it continues for all future tax years.

But, there’s a twist: Even with these cuts to the permanent rates, homeowners will actually see their tax bills increase in tax year 2025, compared to tax year 2024.

That’s because homeowners are paying a discounted rate for 2024, one which is even lower than the newly reduced permanent rate. So, as those temporary discounts expire and the new rate takes effect, bills for that typical home will still increase by more than $300 next tax year.

Commercial properties get a bigger cut

Non-residential properties are getting a bigger tax break — but they also pay much higher tax rates to begin with.

Under the old rates, a commercial property worth $1 million in a typical taxing district would pay about $12,000 in property taxes.

After the two rounds of cuts, most non-residential properties will see their bill significantly lowered. The savings will amp up to more than $1,600 per year, a cut of about 14 percent.

Non-residential properties were a major focus of negotiations in the recent special session. During the earlier negotiations, only certain properties — like farms and developed commercial properties — had received major cuts. During the special session, those cuts were extended to other types of non-residential property.

Long-term limits

The May and August compromises also create protections for property owners against future dramatic increases to their tax bills.

When a property’s value goes up, that usually means a higher tax bill for the owner. But the state’s new tax policies create limits on just how much those tax bills can increase. That’s mostly done by putting caps on how much property tax revenue can grow for individual school districts and local governments each year.

Let’s say property values for existing homes in a county explode by an average of 30 percent in a single year, similar to what happened after the pandemic. Instead of getting to keep all that extra revenue, the local taxing districts would have to tap the brakes. They would lower their tax rates so that, ultimately, their revenues only grow by a certain smaller amount.

The tax revenue increase limit for schools would be 6 percent per year, or higher depending on inflation and enrollment growth. For other local districts, such as special districts and county governments, the limit would be 5.25 percent per year.

In high growth years, those limits could significantly reduce how much more homeowners and businesses see their taxes increase. The new tax code also includes some other state-level limits that could kick in if values grow fast in coming years.

The earlier new law in May introduced some of the new caps on local districts. The August compromise expanded the idea to cover school districts, which make up a major portion of tax bills, and also tightened the limits on local districts.

What would the ballot measures have done?

The ballot measures would have made much deeper cuts and dramatically changed tax policies, which is why lawmakers from both parties were so worried about them.

The tax laws passed this spring and summer totaled about $690 million in property tax savings for tax year 2025.

In comparison, Initiative 108 would have reduced property tax collections by about $3 billion statewide versus the old rates, according to legislative analysts. It would have reduced that typical homeowner’s bill by roughly $400 beyond what the compromise cuts offered. And commercial buildings would have seen their bills reduced by another $1,000 beyond the compromise package.

Those savings would have come at a cost. Initiative 108 would have taken an estimated $2.3 billion out of the state budget to make up for the effects on school districts. By comparison, the compromise tax cuts total just a couple hundred million dollars per year in costs to the state.

Meanwhile, Initiative 50 would have implemented a statewide cap of 4 percent per year on property tax revenue growth, which stirred significant concern about how it would be implemented, how it would affect rural areas and what it would mean for developers.

But even with the reduced scale of the cuts, leaders of some local districts — especially fire agencies that rely on property taxes — are worried about their future revenues. In response, Gov Polis called on state officials to start working with fire chiefs on “creative budget solutions,” with recommendations due by next March 1.

Numerous lawmakers and advocates also have critiqued the process that resulted in these cuts, with some Democrats likening it to “hostage taking,” since the legislature was forced to act by the threat of the ballot measures.