What does community mean to you?

That was the premise of a reporting project CPR News took on this past fall that sought to understand various Coloradans' way of life. Participants shared what their people take pride in, things they don’t understand about others, misconceptions others have about them, and their hopes for a brighter, more collective future.

We spoke with three groups across the state – students from Pikes Peak State College in Colorado Springs, recent Colombian immigrants in Aurora and ranchers and farmers on Colorado’s Western Slope.

Despite the nuances that make these groups unique, we noticed a trend in our reporting. Everyone we spoke with wanted to be understood beyond others' assumptions of them.

Meet the folks we talked with in each of these community conversations and hear their voices below.

This project was part of a bigger collaboration between NPR and nine other member stations, called Seeking Common Ground.

College students talk about the evolution of community

In Colorado Springs, we spoke with four students from Pike’s Peak State College. They represented a diverse group of communities, varying in age, gender, nationality, religious background, sexual preference and political ideology.

This is what they had to say about the ever-changing nature of community, what makes them feel connected and what makes them feel misunderstood.

Interviews have been edited for length and clarity.

Colorado Public Radio: What does “community” mean to you? Can you share a memory or personal story of when you felt connected to or disconnected from your community?

Katherine Atherton, 34, recent graduate: Community can mean so many different things. When I was in my early twenties, I was diagnosed with uterine cancer and I had to go through multiple surgeries and chemo and it was a whole big thing. That puts me as a part of the ‘cancer survivor community.’ [But] I don't identify myself with that community, even though other people might identify me with that community. I have been parts of so many communities and they always ebb and flow.

My communities have always been changing. I can put all kinds of stickers on myself to identify what community I fall under. I'm a queer woman, I'm married, cancer survivor, college student. But sometimes those stickers have to come off and that can be bittersweet, but it also just means that I'm moving forward.

Michael Sanchez, 36, recent graduate: I've been in several communities as well. Before I embarked on my academic career, I worked in adult entertainment. I used to be a musician when I was in my late teens. I was an amateur skateboarder when I was in my mid-teens and each one of those had their own groups of peers and I kind of evolved out of each one as I no longer related to them.

CPR: What might people from other places, backgrounds, or communities not understand about you or your community?

Seth Phillips, 18, identifies as politically independent: [Recently at work] I talked about how I think we need to keep the Second Amendment. I feel like it's an important amendment, right? And I was talking about that. And…this guy, one of my coworkers just kind of turns to me and is like, "Oh, so you hate gay people?" [And] I was like, "That's an absurd jump of the gun there." [Assuming someone falls along party lines] is an absurd thing that I've seen on multiple different cases and I can't understand it.”

Katherine Atherton: I think that nuance is incredibly important when it comes to any community. I mentioned before, I'm part of the queer community, the LGBTQIA+ community. One of the biggest things I've noticed being in this community is that there are so many different ideologies. The biggest thing that connects that community is the belief that we should be able to love who we want to love and be in the type of relationships we want to be in. But even within the community, there are some people who don't believe we should have that. So it is a very nuanced situation.

I remember conversations about people saying that I couldn't identify as a queer woman because I'm married to a man. [But] you can still seek community with people that you disagree with.

CPR: If communities in your area got together more, what would that look like? Who would come, and where would they meet?

Katherine Atherton: There is a significant lack of places for people who are entering into adulthood. You can't go to a bar when you're 19. You don't want to go to a bar to study anyway, but Lord knows you're going to have 2 a.m. study sessions. Where do you go for something like that? Even the libraries are closed and it seems more and more in Colorado Springs specifically, the sidewalks roll up at 9 p.m. So where do you have that you can find and build those community spaces that isn't horribly expensive or prohibitively expensive for those attending? We need more of that in Colorado.

Seth Phillips: I am part of 12 different group chats with the same fundamental six or seven people and they just all are just for different interests…I think that in a way social media is almost becoming a “third space”... Maybe not social media but social networking apps like Discord, like phone call apps, maybe Instagram….I would much prefer to meet up with my friends every week at a location for free… [But] there's very seldom a day of the week that works for everyone.

CPR: Do you think your community works well together to improve things or fix problems?

Katherine Atherton: I think at this point we talk a lot about how there is this massive political schism and society is so divided. And, yeah, in some ways it is, but in other ways we are all desperately striving to be close to each other. We are a communal species and we all really do care deeply about knowing each other, about learning. More often than not, that is what makes me hopeful.

Michael Sanchez: I think the majority of people really do want to come together and we do want to listen, we want to talk and have adult conversations about things. I think the radicals are clearly the minority and that gives me optimism. I think as a society and as individuals, we are becoming more self-aware.

CPR: What is one thing you would want your local representatives to hear from this conversation?

Katherine Atherton: I think there are three major things that I would want our government officials to consider. The first one is listening to the younger generations. I think that we have such an intelligent youth and such a compassionate youth that we should be recognizing and we should be listening to. The second thing is I think we need to look for neutral ground, look to find an even ground so that you're never going to make everyone happy, but let's work to make as many people happy as possible. Let's look to find that even place between these radical ideologies. And that is probably one of the better ways forward. And finally, I'm going to put forward the first tenant that I had in Global Village [a roundtable forum that Atherton led at Pikes Peak State College]... seek first to understand before being understood.

Garrett Koontz, 30, journalism student: You don't have to listen to the loudest people. You can make good decisions without fear of people not getting it. It matters a lot that you explain stuff…especially with younger generations growing up more aware of things. I think there's a lot more ability, and honestly, I'd argue more responsibility to explain yourself better… you don't have to trick people.

New immigrants share their journey to America and the peace they hope to gain

At the courtyard of an Aurora apartment complex mired in controversy, we met a family of eight that had just arrived in Colorado the evening before. They traveled from Colombia, facing adversity every step of the way, whether by crossing the Darien Gap or facing harassment by Mexican immigration officials. They shared their struggles and their search for a new, safer community in the U.S.

The family eventually got placed in another location about a month after our conversation and are hoping to get asylum. We spoke to the parents and eldest daughter and are only identifying them by first name in order to respect their privacy.

Interviews have been edited for length and clarity. English translations provided by Alejandra X. Castañeda.

CPR: What does community mean to you and when have you felt part of a community?

Luis: Community to me is having a union of community to create collaborations for needy people, for people who need help. That to me is a community. And to offer… I mean, come together and look at the needs that children or adults have. Then, to me, to create a community would be that, for all of us to get together and try to help the people who need it.

For example, during the journey from [the] Darién [Gap] to here, to the United States, there have been memories like we saw that happened to us, to other families. In the Darién itself, in the river, there were some pregnant women, and we would arrive and look behind us. “No, this person didn’t make it.” The pregnant [woman], the young woman—as we called her, we didn’t know her name, but we always ran into each other while we were coming—that she couldn’t do it, she was dragging herself because of the pregnancy and like that. When we arrived in the place and she didn’t make it, and people behind us would arrive and say: “No, this person died, they had a heart attack.” But, yes, those are memories you go through.

CPR: What is the situation like in Colombia that made you leave and come to the United States?

Luis: I think in several countries, like for example, in the country we left, mafias also operate there. And in the countries where we were crossing, also. They also don’t take the situation we face seriously. They don’t look at solving it with what the mafias control. They have bought all the government’s laws. And the mafias already have agreements with immigration, with all of that. Then that’s why they don’t do anything for the communities, for the people [like us] who are leaving as immigrants.

I’m here to save my life and my children’s lives, because I left a country that we really escaped because of armed conflicts, that [they] have lived since I went in, since my youth.

And so, if someone asks me here why I came, I have many reasons. I have almost been killed by the mafias. Her [Elisa’s] brother was killed [by them] and many of her family members have died, also killed by the mafias’ armed conflicts, like guerrillas, organized groups, [the] Border Command, [the] Sinaloa Cartel.

Then, my children are already young [adults], they’re already creating community as well. They [criminal groups] arrive in the communities and offer many things. And they make friends there and say: “Here, we’re paying two million pesos, three million pesos to join the groups,” and that’s how they convince them. And they become part of playing soccer, at school, like that. Then, they start converting youth to go, to become part of their groups. And since our towns are very poor, we only live from what we can raise, birds, as they call them here, pigs, all of that, small animals. Then, they come in and become the area’s owner and say: “Well, plant coca, plant this other [thing]. That, food, for what? What we need is for you to grow coca.”

Elisa: And now, already with those armed conflicts, every day, it became even worse, even with my kids in school they were going to threaten them. There, they are forbidden from cutting their hair, if they cut it around here that’s forbidden. If they don’t accept what they say, they go and put them [on] a list to kill them.

Then, that’s why I told my husband: “Well, no.” My husband was also being threatened, because over there everything is killing. Same for my daughter. I mean, her too, with her age already, she was being offered if she wanted to be a wife or the woman of one of them. And if she doesn’t accept it, she’s added to a list. And the one who is going to kill, that one doesn’t have any compassion for anyone.

Then, when they started with my kids, to threaten them and all of that, it was my turn to say we should migrate here, to the United States. Because one wants a more peaceful life, a better [life] for the kids, free from threats, so many things. Because imagine children are being forbidden from getting a haircut, they’re forbidden from [doing] anything.

CPR: If you were a reporter for a day what would you cover?

Luis: What I would like to investigate, report on, like I told you about the mafia people. To investigate why they keep insisting that there be illicit crops in coca areas, like what exists in Putumayo. Like why the government supposedly doesn’t want illicit crops, and illicit crops continue to exist. Then, these armed conflicts arrive to take over the land, the communities where we live. I would like to report [on] that, investigate that, why it doesn’t end.

I would like to investigate that. That sometimes it seems like we don’t understand, but I think I do understand it, that all the money the United States sends to the government they don’t make it work for anything. It doesn’t work there, because the government doesn’t use it really to end those illicit crops, the Colombian government. They don’t do anything against them, rather, the illicit crops increase. And the mafias keep taking over the farming communities. Yes, that’s what I would like as a reporter; I would investigate that more in depth, why that isn’t ending.

Darcy: Well, I’d investigate why they kill minors. They kill only because they upload a photo with an iPhone or because they upload [it] with a gold chain. I would like to investigate that, because they have killed several 14- to 15-year-old boys over there in Colombia, where I lived. They would take off their fingers. And, well, like that. That’s how we would get the news. Why they kill just because someone uploads a photo, let’s say, only with a chain or with a watch, and they think that you have money, and they’re jealous and they kill you. That’s what I’d like to investigate.

CPR: What is one thing you would want your local representatives to hear from this conversation?

Darcy: That they listen to us. That they listen to the story of what we went through to get here, everything we suffered in Colombia to be here. And, yes, that they help us. I would tell them the entire story from the moment I left the jungle until [I got] here so they can see.

Luis: That they listen to us, like to all immigrants, that we really do deserve some help, because there, let’s say, there are many immigrants that come here for other things. Because sometimes there are immigrants that leave because of crime or like that, and they come here to do the same. And that they listen to us, to each person, that we really do need help.

Ranchers and farmers talk about growing pains on the Western Slope

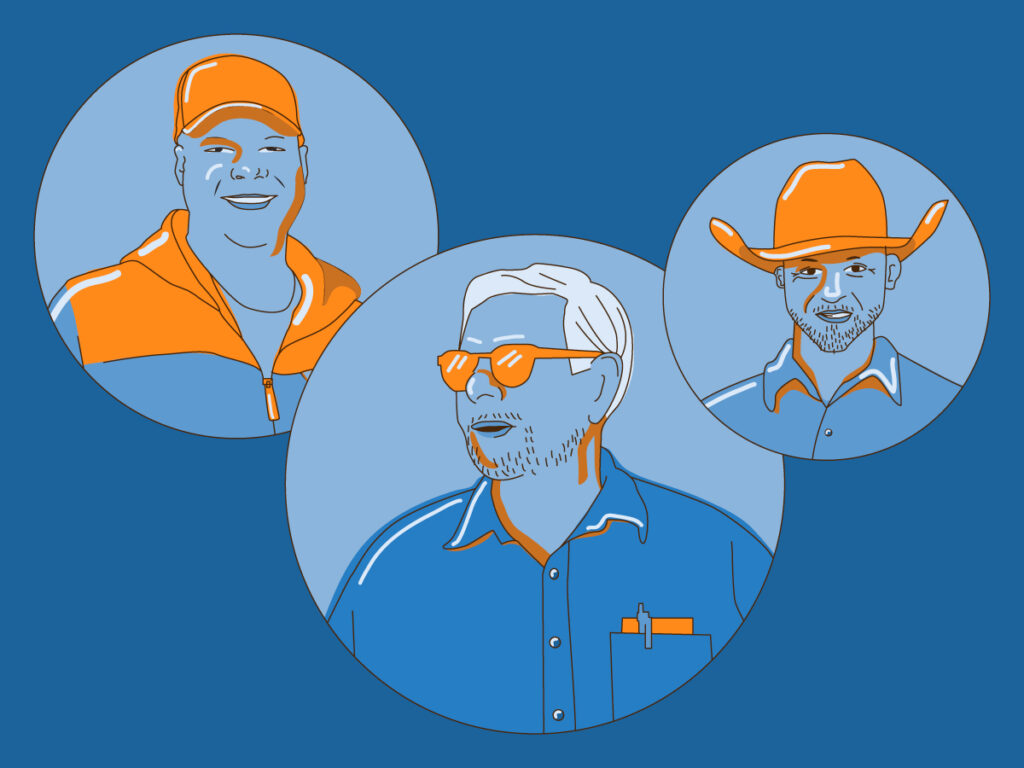

Other folks we spoke with as a part of the ‘Conversations across the Divide’ project were agricultural workers on the state’s fertile, Western Slope. One is a cattleman, one is an orchard and vineyard owner and one is a microgreen farmer. Two grew up in the area. One moved to Colorado from Kentucky. All three have noticed change in recent years, due to the area’s increasing popularity.

Here’s what they shared about the joy of life on the Western Slope, the challenges of a growing community, and what they wish outsiders understood about their livelihoods.

Interviews have been edited for length and clarity.

Colorado Public Radio: What does “community” mean to you? Can you share a memory or personal story of when you felt connected to or disconnected from your community?

Nathan Strouse, Grand Valley Micro Farms: Growing up, [Grand Valley] definitely had a stronger sense of [community]. I've heard stories from others back in the day, during the Great Depression, where they would all come together. Someone would grow a certain crop, someone would raise pigs – and they really actually thrived through the depression period because of that community. Everybody carries their part. Of course, as things grow – which there's benefit to that – there's also less community feeling.

Brady Pearson, Razor Creek Beef, LLC: Out in Loma, everyone's our neighbor – whether you're two miles away or five miles away. It does seem like everybody is trying to help everybody. There'll be situations where, say, we'll have a piece of equipment break down. Man, we've got three guys on the phone, "Hey, what can I do for you? How can I get you... Oh, let me see if I got parts."

[But] we've had a few minor issues with people out of state…out there, even though the speed limit's 50, most of us don't drive 50. It's 35 or whatever because we're checking water and doing different things…we have livestock dogs, kids, there's people on four-wheelers. There just seems to be getting more and more people out in that area, which is fine, but it would be nice if they'd be a little more respectful.

CPR: What might people from other places, backgrounds, or communities not understand about you or your community?

Brady Pearson: The cows aren't going to ruin the planet. That's my number one thing. You hear stuff all the time about, "Oh, the cow farts," and this and that. If you go spend time horseback with me or even just around our farm and stuff, there is no smog, no nothing. That's probably my biggest issue right now, is that they're trying to demonize the cattle industry as a whole: dairy, beef, whatever. We're not out there trying to ruin the planet at all. We look at ourselves as environmentalists in a way that we want the best for the ground and the earth too.

[And] I'm not against solar at all. I think we need to be using all energy sources wisely. But to take out agricultural ground that's fully developed just seems silly to me. If they would find some less useful ground, then that would be a smart decision.

CPR: What is one thing you would want your local representatives to hear from this conversation?

Philip Patton, Peachfork Orchards & Vineyard: I've had land for 30 years and the value of the property is going up to where farmers can't afford to farm. My taxes have gone up 44%. I'm all about funding the schools and I know we have to have roads and all that stuff, but the cost of land and the taxes has tremendously gone up in the last few years.

How can a young person buy a farm and try to pay for that farm? It almost has to be somebody older or somebody from outside the valley to buy that land. It's getting harder and harder to farm.

Nathan Strouse: The population here is increasing and that's not going to slow down – and people need places to live. There's what you would call more fertile land in the valleys, and then there's more non-fertile land, so maybe focus on studies on where to build housing developments? How do we maximize affordable housing for people and also keep the agricultural community strong?

CPR: What makes you all optimistic about the future of your community, if you do feel optimistic about it?

Nathan Strouse: [Regarding] growth, sometimes it can seem like things build too fast and move too fast, but it's also good for the economy…For the future, as long as that skeleton [of community values] remains, I think we have a positive future here.

Phil Patton: We can't imagine what the world is going to be like…don't say anything won't work because we can't imagine….The world is not going to come to an end. …I think it's going to be way better in the future.

I have a 19-year-old and a 22-year-old that worked for me. We think differently and we do differently, but they work hard. So just be optimistic.

Brady Pearson: There's a lot of good youth out there. There really is.

Arlo Pérez Esquivel contributed to this report.