At just 15 years old, Jason has insight now into how his mind works that most teenagers don’t. He can name how he’s feeling and knows what to do when his emotions get too big.

It wasn’t always this way.

As a child, Jason’s home life was turbulent. We are not using the students' last names to protect their privacy. His mother had a serious mental illness and things became explosive. The children were put into foster care for a spell. Everything spiraled downwards in middle school.

“In sixth grade, I was doing a lot of immature things,” he said. “I was getting suspended almost every day, almost every week.”

After school, Jason and his friends would write graffiti on homes and steal things.

“I would smoke weed and think it would cure my pain and help me with a lot of depression and anxiety, and then once my brother found out he disciplined me and he kind of beat me in order for me to stop those things.”

Then Jason arrived at AUL Denver, a small alternative high school in the city’s northwest. His life changed. The school is one of a growing number that seeks to not only educate children but to help them deal with their social and emotional health in a way that ensures they can be successful academically — and in life.

“Honestly if I didn't change, I would probably be in a gang right now.”

Nationwide, experiments in redesigning high schools are taking place

Thousands of high school students fall through the cracks.

Here’s why: Most large high schools aren’t designed to help teens learn the skills that are critical to healthy teen development. Instead, their focus is on making sure kids are in seats ready to absorb academic information. Meanwhile, teenagers are experiencing intense emotions. It’s a time of life when mental health issues start cropping up. They may have other challenges like an unstable home life. Teens have no idea how to process the big emotions they’re feeling.

“At my last school people were always fighting because they didn't understand other people's point of views, like they didn't know what people would go through,” said Gianna, 15, a student at AUL Denver. “Here everybody really knows what people go through and what they have going on in their lives. So, it's more calm … Everybody here is really calm with each other.”

But it’s taken time to get here. Social worker DonDre Harris said when he arrived at AUL a couple of years ago, he noticed that when there was a disturbance or misunderstanding, staff reacted with discipline.

“We were being reactive to them instead of proactive,” he said. “I realized these students are lacking certain skills. A lot of these issues that we're having could be easily resolved if they were getting these skills in a classroom setting.”

So AUL shifted to explicitly teaching students social and emotional skills in classes and making conversation circles central. Student well-being and interpersonal skills are prioritized. It’s one model of high school redesign that recognizes that strong, positive relationships between educators and students are necessary for students to succeed.

In a lively social and emotional skills class, on a crisp December day at AUL, the kids play a deduction card game called “The Werewolves of Miller’s Hollow.” It teaches students how to make decisions. Teacher Saladin Thomas said kids at first think the game is kind of silly.

“Then a couple of cards into it, they’re like, ‘Wait a second, this keeps happening,’ like they're practicing those decision-making skills, they're practicing those reasoning skills, they're practicing inference.”

They talk about whether it’s best to listen to the loudest voice in the room, to go with your gut, or to use evidence. At some points, kids get the sense of what it feels like to be “othered” but in a safe environment and they talk about it.

Harris says since the social-emotional model was implemented, they’ve seen a big change in students' overall well-being and mental health.

“They feel seen, they feel heard and they feel validated. I think that that's why we have the success with the students who haven't been successful at other schools.”

By the time a student lands at AUL, they’ve had a lot happen in their young lives

Some arrive from the juvenile justice system or felt shut out at their previous schools, “feeling like their voices aren’t heard, their cultures aren’t being reflected in those spaces,” said Principal Frank Lee.

“We’ve had students who’ve lost tons of family members at a very young age, family members who’ve been incarcerated, family members who’ve been victims of police brutality, so they’re navigating all of these different things as children.”

The students may carry around a lot of anger, anxiety, confusion, and depression. All those things can make it harder to keep up with classes. The circles are the first time many have been able to process how they’re feeling — and come to know they aren’t alone.

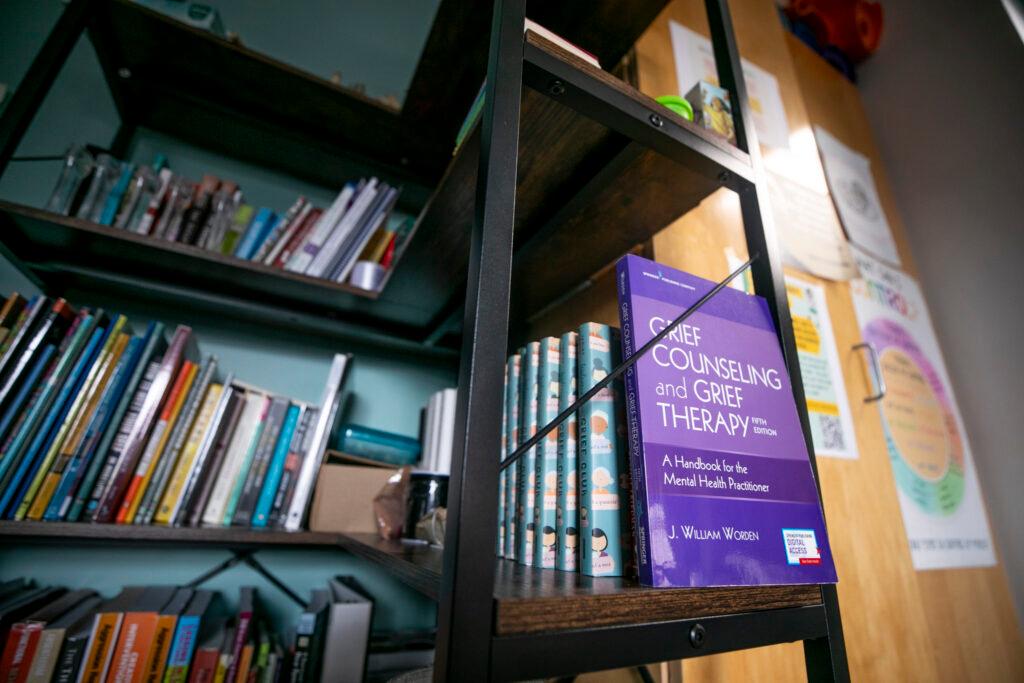

It was AUL’s focus on emotional skill-building and students’ participation in “circles” – circles for grief, circles for communication skills, a circle for boys, another for girls – that was just what Jason needed.

One of the groups Strong Minds, Strong Men has helped him mature.

“How do we get stronger in relationships? How do we build bonds? Our life, like, how we get better and how we do better? We use those types of conversations to improve each other.”

On days when his emotions are too big, he’s able to have a one-on-one conversation with one of the counselors and he says, 20 minutes later, he’s back in the classroom.

“When you express your emotions and you express your feelings to other people, they cherish it, they hold it, and let you know you can become a better person every day,” he said.

Gianna, 15, said she has bad social anxiety but in the school’s girl group, she’s talked with five girls she doesn’t normally talk to and sees that they have a lot in common. She’s learned how to express what she needs instead of bottling them up.

“I've learned to be really open about what I need help with, like if I ask a teacher for help, I'm not gonna get shut down …. I've learned to be open.”

Gianna felt that some teachers at her old school just didn’t care about her. She didn’t have a sense of belonging. At AUL she shows up every day. She has good grades. She gets the help she needs to graduate. The staff will even send notes home.

“I like that because it's showing that I'm trying and it's showing that they noticed that I'm trying and that they noticed that I'm doing better.”

On the alternative schools rating system, AUL met targets last year for growth in reading, writing and math. The school still struggles more than most schools with attendance, but it’s exceeding expectations in dropout recovery. Last year it graduated the most students in the school’s history.

“The data that we've looked at is trending upward,” Lee said.

Last year the school started an academic probation program called “Wolfpack Watch,” where students in the program get individualized learning plans, have their attendance monitored and can receive ‘success points.’ Students can clearly see what they need to graduate.

There’s also a fund to help students in emergencies, like Isis, 20, a young mother who got behind on her rent once. She calls the school “a safe haven.”

We head into a circle

The morning light is soft on the teens’ faces.

They sit in a circle shoulder-to-shoulder on couches. A girl clutches a big orange “emotional support” stuffed animal named Josh. Today they’re talking about how they feel when the person you’re talking to isn’t really listening to you.

“It kind of isolates you and it puts you in a position where you don’t feel comfortable advocating for yourself because you feel like you’re going to be shot down and you’re not going to be taken seriously,” said Isis.

Elijah, with long hair in a dapper tan long wool coat, agrees.

“It sucks to not feel acknowledged like when you’re talking and they go … 'What?’”

The group nods and murmurs affirmations. Harris, who is big on encouraging kids to befriend their emotions (he calls his anxiety “Cruella” after Cruella de Vil), gives the teens tips on how to communicate better.

“For me, I’ve learned to be intentional about who I’m going to and for what because every friend doesn’t have the capacity to listen to and respond to what you’re sharing,” he said.

The kids say they relate to Harris and restorative justice coordinator Zeta Arellano who tells the students about how their mother gave them the silent treatment growing up. This opens the door for the kids to talk about how they learned to communicate.

“I had past connections where whenever I messed up, they would completely shut me down and say, ‘Figure out what you did wrong,’ instead of telling me what I did so I could fix what I messed up,” said Elijah.

A lot of these students have had to learn how to muddle through life on their own.

“Everything I’ve been through in my life, it’s taught me how to do the opposite,” said Gianna.

“That’s generational healing,” explains Arellano. “A lot of us carry generational trauma. That’s real.”

Arellano, who uses they/them pronouns, explains as they got older, they realized that their mother probably learned the silent treatment from her mother. Arellano decided to break the cycle with their own daughter, teaching her how to communicate when something’s bothering her or she’s mad at Arellano.

The tail of Pistola, a therapy dog, thumps as he wanders among the kids.

Gianna tells the group both her parents died when she was young and that shaped her into the person she is today. That prompts another girl to speak.

“I agree with you, I agree with you. ‘Cause I lost my parents too when I was young and if I didn’t lose them …” her voice trails off. “You wouldn’t be the way you are,” finishes Gianna.

Giana gets up and gives the girl a hug. That connection and knowledge that another student has had similar experiences and they are not alone is huge, say school leaders. The students are mirrors of each other.

“You need to go through something to make your bones strong” — or not

The conversation veers into some kids musing that their hard backgrounds prepared them for life. Another ponders if the beatings he received toughened him. Another says everything happens for a reason. Gianna said you need to go through something to make your bones strong.

“Life is not always so sweet,” she said.

But Isis disagrees. She said it sounds like the students are saying bad things are inevitable and they deserve what happened to them.

“Me as a mom, I’m going to make sure that the worst thing that happens to my daughter is something that could be fixed. I don’t want them to be anything like the things I went through because I don’t think I deserved that at all. I don’t think you guys deserved any of the things you went through …. If we were all given the same opportunity to grow up in a stable home, with good healthy parents, we would all turn out good, the same way we are now.”

With the counselors’ help, the group talks it through. They clarified that what one group of students meant was that what happened to them in their past were just the cards they were dealt. They’ve acknowledged it made them who they are in the sense that they’ve learned from it — and won’t repeat the mistakes of their parents. Isis, who since age 12 moved every year from group to foster home, said she is not ready to leave the pain of her upbringing behind. She has too much anger.

Arellano uses the moment to explain that everyone is at a different place in their healing and how they relate to their past.

Gianna tells Isis she and the other kids aren’t fully healed either.

“We agree with you … because I’m still mad … but I also can’t (be every day).”

“I hear you guys,” Isis replies, “and maybe I can get to that point.”

When asked for concluding thoughts before the circle breaks up, a boy who has mostly been quiet speaks up.

“You aren’t where you come from. You are what you build yourself to be.”

Yes. yes. yes. There are nods and smiles around the circle. The students gather their things and give Pistola a pet.

“I hope everyone came out of this conversation feeling a little lighter, kind of like a weight lifted off your shoulders,” Isis says.

“I hope everyone knows you guys are loved,” Eva adds.

With that, the kids shuffle off to their next class.

“The groups,” says Isis later, “they give me strength and guidance for my life to just help me keep moving forward.”