Updated on Monday, March 24, 2025, at 4:46 p.m.

A UCHealth patient made a bit of history Friday as the first person in the nation with Parkinson's disease to experience a treatment doctors are calling groundbreaking.

The patient's name is Kate. She's 75 and has struggled with Parkinson's, a progressive neurological disorder that affects movement, balance and coordination, since 2019. There is no cure for the condition that often causes tremors and speech changes. It affects nearly 1 million people in the U.S. and an estimated 10 million people globally.

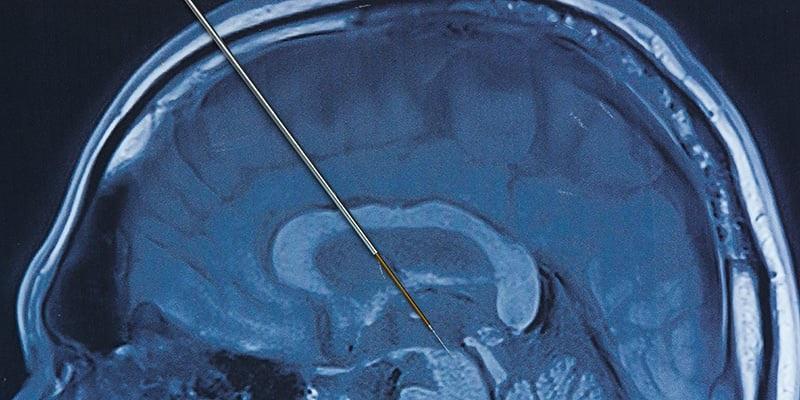

At UCHealth University of Colorado Hospital on Friday, with reporters and photographers looking on, doctors showed how electrical messages, controlled by a computer program, can be sent to electrodes implanted in a patient’s brain to ease symptoms, like trembling hands or fingers.

Kate said the treatment seemed to help.

“It's been a long time, and I have grandchildren. I really want to see my grandchildren, see them grow. And it's given me hope,” she said. “It helps. It's a tremendous help.”

This new treatment is one of the fruits of research conducted by Dr. Drew Kern and Dr. John Thompson, associate professors in the department of neurosurgery at CU School of Medicine and physicians at UCHealth.

The researchers activated the technology, enabled by the electrode surgically implanted in Kate’s brain and controlled by a program on a computer pad, for the first time outside of the research setting.

Deep brain stimulation has been around for more than three decades and has also been used to treat epilepsy. The big advance being shown off at UCHealth University of Colorado Hospital is what the company behind it calls a new system that adjusts the therapy to “individual brain activity in real-time.” Kern said it marked a major step forward in the fight against Parkinson’s disease.

He showed the difference in Kate’s ability to do basic motor movements like moving her thumb to touch her fingers, pivoting her wrist, tapping her toes and walking across the room. As the computerized system adapted electric messages being sent to her brain, it appeared to improve her motor function.

When asked if the breakthrough could help many others with the disease, Kate’s partner, David Julie, said he hoped so.

“To us, it seems extremely promising. And the results you saw today, and she had a sample experience a week ago, the results were really positive,” Julie said.

As the technology evolves, Kern said he was hopeful it could be tailored for individual patients.

“Is this most helpful when the person is sleeping? Is this most helpful when the person is very active? Is this most helpful to adjust the programming when the person takes medication?” Kern asked. “We do know, and publications are coming out, that it does improve the amount of ‘on time,’ meaning when the person feels good throughout the entire day.”

The team identified a biomarker in the brain that makes this treatment, called adaptive brain stimulation, possible. It adjusts in real-time using the patient’s own brain signals, with the Medtronic technology, which was approved last month by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

The advance promises to dramatically improve the management of Parkinson’s symptoms by providing a personalized, responsive treatment that can change with the needs of each patient.

The researchers said it was gratifying to be part of a project that could help thousands of patients with the condition.

“It's an honor to be a part of this process to, as a basic scientist, be able to play a small role in improving the lives of these patients. So it's been amazing to be a part of the process,” said Thompson.

Kern said the adaptive stimulation technology enables patients to dial back the use of medications, which would save them money.

“The cost of Parkinson's disease is quite high, and if you're able to improve their longevity, especially by reducing medication by 50 to 75 percent, it actually becomes cost-effective for the individual and then therefore for society,” he said. “Individuals who already have this type of system can be programmed, so your doctor could be able to program you in a matter of probably less than an hour…with this new system to potentially improve, hopefully, your overall function.”

The treatment requires a pair of surgeries. With deep brain stimulation, doctors implant electrodes in a specific spot in the brain. In the second procedure, they put what’s called an implantable pulse generator, which is like a heart pacemaker, under the skin, usually under the collarbone. Kern showed journalists the one Kate has. That device sends messages to the brain that control movement. The computer control helps manage the pulses to the brain, thus treating motor problems that come with Parkison’s.

The researchers said federal money through the National Institutes of Health helped fund the research. Now money is potentially at risk with the new federal administration and Congress looking to slash the budgets of national health agencies.

Editor's note: This story has been updated to reflect which hospital provided care for the patient.