This story is part of the Hotspots series exploring Colorado's geothermal energy industry by CPR's Climate Solutions Team. Explore the series here.

Fred Henderson doesn’t expect to live long enough to see the completion of Colorado’s first geothermal power plant. At 89 years old, the retired geologist is trying to keep his dream alive by proving he’s found a good place to put the facility.

“I want to see that ‘X’ on the ground. I’d like to be around to see that happen,” Henderson said.

More than a decade of research has convinced Henderson he’s found a suitable location near Buena Vista. It’s a lightly wooded hollow below a county road packed with yucca plants and sagebrush. A barbed wire gate guards the parcel of state land Henderson and his business partner, retired lawyer Hank Held, lease through Mt. Princeton Geothermal, a company founded by the duo in 2007.

The site sits a couple of miles from Mt. Princeton Hot Springs Resort. Since 1879, the resort has drawn tourists to Chalk Creek Canyon, a former mining district where mineral-rich water bubbles out of the granite at temperatures as high as 183 degrees Fahrenheit.

By tapping the underground heat, Henderson and Held promise to provide a zero-carbon electricity source that doesn’t fluctuate with the weather and time of day. Consistent energy could be critical as Colorado shuts down its coal-fired power plants. Without new types of 24/7, firm electricity, a state analysis found that Colorado would struggle to meet its climate goals without building far more wind, solar and battery storage systems, which could saddle households with higher energy bills to cover the cost.

The potential benefits have transformed Gov. Jared Polis into a leading geothermal energy advocate. In 2023, he launched the Heat Beneath Our Feet initiative to encourage geothermal development in Colorado and other parts of the western U.S. The governor’s office has also established tax credits and grant programs for geothermal electricity production to support entrepreneurs and their investors.

Mt. Princeton Geothermal, the venture founded by Held and Henderson, hopes its plan will spark a new statewide industry. The company won an initial state grant last year to drill research wells at the proposed site. The money, however, is conditional on the company earning state and local permits to dig roughly a mile below the proposed power plant site.

Meanwhile, an opposition movement has gained traction as the proposal inches closer to reality. A local group of residents warns the power plant could bring excessive lights, noise and steam to the picturesque mountain valley. Another contingent fears the plan could disrupt the area’s world-famous hot springs and its associated tourism industry.

The battle is now an early test for Colorado’s young geothermal industry. If Held and Henderson can’t overcome their opponents, it could send a message to potential investors: The state might want geothermal power plants, but its residents don’t want them in their backyards.

An energy source with a deep past

Held and Henderson are far from the first entrepreneurs to imagine generating power from underground heat.

Piero Ginori Conti, an Italian prince and industrialist, used steam escaping from geysers outside Tuscany to illuminate light bulbs in 1904. Less than a decade later, he developed the first commercially viable geothermal power plant in Larderello, Italy. The city is now home to steam-powered facilities that feed energy across the country.

The first geothermal power plant in the U.S. opened in 1960. Located in northern California, the complex, known as the Geysers, harnessed superhot steam blasting out of the ground to drive turbines. The power plants continue to provide the state with one of its largest sources of carbon-free electricity. Other geothermal power plants operate in Hawaii, New Mexico, Utah, Idaho, Oregon, Nevada and Utah, producing less than half of 1 percent of utility-scale power generated in the U.S.

There’s now a rare bipartisan consensus around expanding the sector. Former President Biden’s administration launched initiatives to cut the cost of geothermal energy production. Since President Trump recaptured the White House, U.S. Energy Secretary Chris Wright has thrown his support behind the industry, noting that geothermal power could support data centers and help bring factories back to the U.S.

Wright also hasn’t shied away from the potential synergy between geothermal and fossil fuels. Both require someone to drill, baby, drill. Both could also benefit from the fracking technology he helped develop at the oil and gas company Liberty Energy, based in Denver. To enhance geothermal energy, some startups plan to use fracking to crack open dry, hot rock, then flood the fissures with water to harvest the underground heat.

The developments could help geothermal energy someday thrive far from volcanic areas and hot springs. At the moment, however, Mt. Princeton Geothermal plans to follow a more proven path by generating electricity from underground hot water.

Prospecting for underground heat

Henderson started looking for a thermal reservoir long before the federal government took a new interest in geothermal energy.

A Harvard-trained economic geologist, Henderson spent decades prospecting minerals for private clients around the world. After joining his wife in Chaffee County, she suggested he redirect his talents to tap some of the region’s famous geothermal energy for their own home. “She wanted me to get off my duff and find her some hot water,” Henderson said.

Held, his business partner, said a similar impulse led to his interest in geothermal power. The retired lawyer and investor had grown up in Chaffee County. His family spent summers in a cabin above Chalk Creek, and Held and his brother would often soak in warm rock-lined pockets below Mt. Princeton Hot Springs Resort. Even as a kid, he wondered why someone wasn’t putting the heat to use.

After returning to the region in the early 2000s, rising oil prices led Held to consider harvesting underground heat for electricity instead. His research put him in touch with a professor at the Colorado School of Mines, who later introduced him to Henderson.

The pair met and hit it off, Held said. At first, they hoped to build a power plant closer to the hot springs, but their initial exploratory drilling caught the attention of Chaffee County commissioners, who placed a moratorium on any geothermal electricity development before approving rules to regulate the industry in 2013.

The setback scared off Canadian investors backing the original power plant proposal. During their work on the project, however, Held and Henderson began to consider whether it’d be better to place their proposed power plant further from the canyon.

It was an idea supported by an earlier attempt to harvest geothermal energy. In the heart of the 1970s energy crisis, Amax, a company behind a molybdenum mine near Leadville, drilled test wells near Buena Vista in the area to search for steam to generate electricity. Held said the company dropped the idea due to regulatory pressure and dropping fossil fuel prices.

Henderson obtained the company’s data taken from exploratory wells the company drilled around Mt. Princeton between 1973 and 1975, and a study partially based on the findings suggested the existence of a major geothermal aquifer deep in the valley below Chalk Creek Canyon.

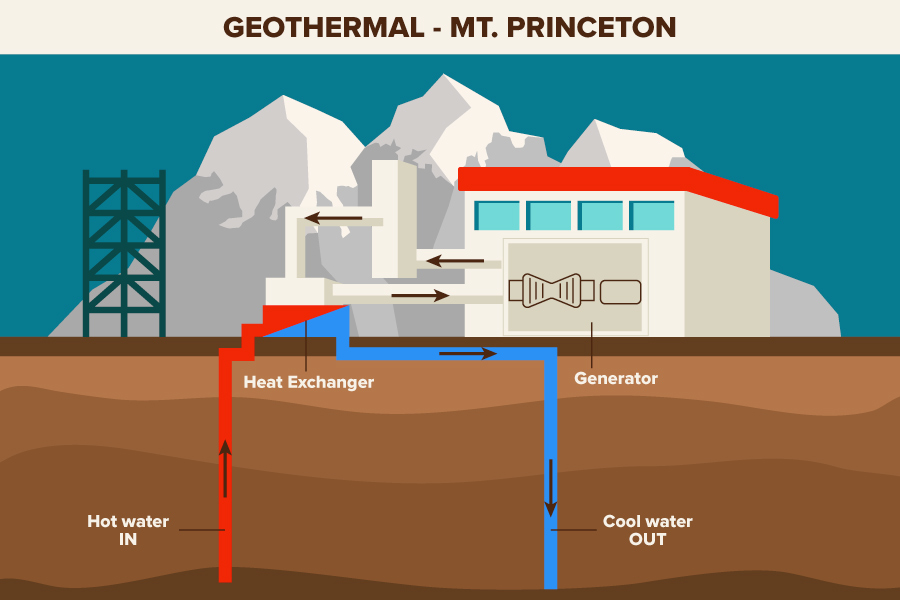

By drilling two boreholes, Mt. Princeton Geothermal aims to confirm it could tap into the aquifer hidden deep below the surface. A final power plant would pump water up through a heat exchanger, then spin a turbine to generate electricity before injecting cooler water back underground.

“I’m betting 99 percent it’s going to be good hot water. We think we have a drill site ready to prove it, and that’s what we’re trying to do,” Henderson said.

A potential boon for the community

Held and Henderson are also confident that their project would boost the local economy.

The duo estimates the facility could initially support a 10-megawatt facility capable of powering 6,000 to 8,000 homes. Held said that’s enough to power the entire service territory covered by the Sangre de Cristo Electrical Association, the local electricity cooperative for most of Chaffee County and other parts of central Colorado.

If another utility or technology company purchases the power instead, he said the $40 million investment to build the power plant would still add around 15 full-time jobs and provide a major boost to property taxes to help fund schools and other local public services.

New public and private funding commitments are now pushing their plan closer to reality. In 2024, Mt. Princeton Geothermal was awarded $500,000 to drill the planned test wells through Colorado's Geothermal Energy Grant Program.

Soon afterward, the company announced a prospective merger with Western Geothermal and Reykjavik Geothermal, two firms working to export Iceland’s expertise in geothermal energy. The island nation relies on geothermal facilities to generate a quarter of its electricity, and 90 percent of households are heated through local networks built to deliver geothermal energy.

Gudmundur Heidarsson, an Icelandic-born entrepreneur behind Western Geothermal living in Evergreen, Colo., said his firm aims to support a series of geothermal power plants across this state. It’s starting with Mt. Princeton by offering an additional $500,000 to match the state grant to dig the research wells at the proposed site, which he’s confident will prove the location sits atop a viable geothermal reservoir.

The bigger challenge, he said, is winning public support. Without it, the concept could again run into trouble with local regulators. “It’s easy from a geological perspective,” Heidarsson said. “We have to have the community in agreement with what we’re doing.”

Henderson, meanwhile, has lost patience with anyone unwilling to see the benefits of moving ahead. At the proposed power plant site, he pointed toward Lost Creek Ranch, a nearby subdivision hidden from view but home to many residents fighting the project.

“Why do they care that much about it? I don’t know, but they do,” Henderson said.

A heated opposition movement

On a rainy evening last October, Blane Clark, a retired accountant living in Lost Creek Ranch, welcomed a crowd gathered in an American Legion hall in Buena Vista.

Dozens of residents braved the weather to listen to a presentation about concerns over the proposed Mt. Princeton Geothermal plant. Clark co-founded Save Our Arkansas Valley in 2024 to advocate against the project.

He kicked off the meeting with a clarification: the group doesn’t oppose the concept of geothermal energy. While it's clear the power plants could offer some benefits, he said almost all of them were in far more remote places. “What we are saying is that the location is stupid,” Clark said.

The proposed site along County Road 321 borders a state wildlife area home to elk and pronghorn antelope herds. One presenter raised concerns that drilling and construction could disrupt migration routes through the area.

Another opponent played a recording obtained by driving his motorcycle hundreds of miles to the Blue Mountain power plant in Nevada, which generates geothermal electricity. He warned that a similar high-decibel hum could someday disturb humans and animal residents living along the Arkansas River.

Mt. Princeton Geothermal insists its final design will address those concerns with sound buffers and steel casing to protect nearby water from contamination. A system to cool geothermal water with air would also eliminate any risk of an unsightly steam plume, Held said.

Residents also noted examples of environmental mishaps linked to geothermal projects in other states and countries. An attempt to draw energy from bedrock near Basel, Switzerland, shut down in 2009 after a study linked it to a series of small earthquakes. That project, however, tested “enhanced geothermal,” which uses techniques similar to hydraulic fracturing known to increase the risk of small earthquakes in certain areas. Henderson and Held have reiterated that their project only requires conventional drilling.

Heidarsson, the Icelandic investor, attended the entire presentation. At the end of the meeting, he revealed himself and took the microphone, telling the crowd the discussion confused him because “it doesn’t necessarily tie into what we are doing.”

The mood quickly turned sour. Heidarsson asked if anyone had visited Iceland to see the full potential of geothermal energy. Someone in the audience then shouted to ask if he’s a U.S. citizen. “I am,” Heidarsson responded. “Is that pertinent to this?”

Heidarsson took a breath. He assured the crowd that the project would follow strict state and local regulations. When asked why the power plant had to sit below Mt. Princeton, he said the location was simply the most thoroughly researched potential site in Colorado.

But those points failed to calm the fury rising from the audience. As the event wrapped up, an attendee approached Heidarsson to deliver a parting tirade. “Go back to Iceland and stay there,” he said. "Go sit in a hot tub.”

Heisarsson grabbed his jacket and left for his car.

A worried hot springs industry

The tenor of the conversation surprised Syd Schieren and Erin Oliver, a pair of long-time Chaffee County residents living just above Mt. Princeton Hot Springs Resort along Chalk Creek.

The couple attended the meeting due to their concerns about the power plant. Since the 1990s, they’ve relied on a geothermal hot spring to heat their home and feed tubs outside a set of three rentable vacation spots on their property. The hot water also maintains a year-round temperate climate inside a greenhouse roughly the size of two tennis courts.

For decades, Oliver operated a commercial growing operation out of the facility, mostly selling salad greens to local restaurants. Since winding down the business a few years ago, she has filled the space with a riot of cut flowers, banana trees and her favorite tomato and pepper varieties.

If a power plant taps the same hot water source and re-injects colder water underground, Schieren fears it could cut the temperature of the underlying aquifer, potentially affecting their tourism business and other historic hot springs along Chalk Creek.

“The geology here is just really complex with this fractured granite. It’s really difficult to map how the water moves through the whole area,” Schieren said.

It’s a concern shared by Thomas Warren, the general manager for Mt. Princeton Hot Springs Resort. In late 2024, the company hired a hydrologist to model how the power plant could impact hot spring resources in Chalk Creek. The analysis shared with CPR News found the project might reshape underground forces pushing water to the surface. As a result, the power plant could reduce the amount of spring water flowing into Chalk Creek and the Arkansas River, raising questions about whether the project could run afoul of Colorado’s strict water rights protections.

Other hot springs operators have squared off with geothermal energy developers around the world. In Japan, similar fights have impeded attempts to exploit the nation’s ample underground heat. In New Zealand, geothermal projects diminished historic geysers and hot springs before a preservation project began in the 1980s.

Colorado’s hot springs industry is determined to avoid the same fate. During the current legislative session, operators like Warren opposed a bill to streamline the state permitting process for geothermal drilling projects. That led lawmakers to add specific amendments to protect historic hot springs across the state.

Held, the co-founder of Mt. Princeton Geothermal, insists Colorado’s strict regulations will safeguard nearby hot springs. The company plans to hire an engineering firm to complete its own hydrology report, which it will submit to the Energy and Carbon Management Commission, a panel that’s traditionally overseen Colorado’s oil and gas industry.

The company must gain a series of approvals to begin drilling its research wells, including permission from the Chaffee County planning board, the ECMC and the state land board. If the company finds a viable geothermal reservoir, it then must survive a separate state and local permitting gauntlet before building the power plant.

It’s a tough road with multiple opportunities for public comment. Held, however, hopes Mt. Princeton Geothermal can win over regulators and begin drilling its research wells by the end of the year.

That’s the moment Henderson hopes to experience before he dies. As a geologist, he said his job has always been to find the raw materials necessary to keep the modern world running long into the future. Evidence of abundant geothermal energy below Mt. Princeton, he said, would suffice as a final legacy.

“I worry about the next generation. We’re all consumers. We consume everything,” Henderson said. “This is the best energy source, in my mind, for the future of this county.”

Editor's note: This story has been corrected to reflect which county road the proposed site is near.

- Colorado’s hot spring operators are getting nervous about geothermal energy

- Colorado is ready to help pay for geothermal heating and cooling systems

- In Colorado, U.S. Energy Secretary Chris Wright says climate change alarmism has hurt energy development

- CU will use geothermal power on campus — as a test — on its way to zero emissions

- Gov. Jared Polis pushing last-minute bill to accelerate Colorado’s shift to renewable energy

- What to know about Colorado’s hot springs and where to find them

Funding for public media is at stake. Stand up and support what you value today.