This story is part of the Hotspots series exploring Colorado's geothermal energy industry by CPR's Climate Solutions Team. Explore the series here.

On a gusty day in February, Ben Burke and Johanna Ostrum toured Jennings 1, an idle oil well in Pierce, Colorado. Hemmed in by a fence and ringed by homes, the well looked unremarkable.

But for Ostrum and Burke, who run Gradient Geothermal, wells like these offer an opportunity to transform fossil fuel relics into climate-friendly heat and electricity.

“ Millions of dollars have been spent to drill these wells deep into the ground, and they no longer produce oil and gas that's economic,” said Ostrum, Gradient’s COO, during the tour. “But they have tapped a heat resource, and just plugging those wells seems like a gigantic waste to me.”

Idle wells like these dot Pierce, a small town in Weld County, about 30 minutes from Fort Collins. Engineers discovered the “Pierce field” in the 1950s, and it produced oil for decades. As the oil became scarcer, the wells mostly pumped up scalding mineral-rich water — normally a waste product of oil production. By the late 2010s, operators shut down all of the town’s wells.

That hot water, though, presents an opportunity for geothermal energy, which taps into the Earth’s heat. Gradient’s idea is to repurpose the water’s heat to replace traditional heating and cooling systems in buildings.

The water could also be used to make electricity for the grid, according to another entrepreneur, Gary McDaniel, who leads Geothermal Technologies, Inc. It is fundraising with the aim of turning the same sediment-rich water into a power plant that works around the clock.

“It’s the ultimate renewable power supply,” said McDaniel, a serial clean technology entrepreneur who’s bullish about geothermal’s chances. “It’s nearly perfect power.”

These projects are among the first of their kind in the country, though they are still in their infancy — no power’s been made, and no wells ramped back up. Colorado is lending them financial support to get started, in the hopes they can help the state meet its ambitious climate goals, and may provide a way to move local economies away from fossil fuels.

Paradoxically, the fact that Pierce is home to two potentially groundbreaking clean energy projects is largely because of its oil roots. The town sits in the Denver-Julesburg basin, an oil and natural gas hotspot. For decades, engineers and geologists have pored over the region’s features to extract fossil fuels.

Now, McDaniel, Burke and Ostrum are using some of the same data in their plans to extract hot water for renewable energy.

If these projects are successful, Pierce may one day be defined by geothermal energy; McDaniel said it may be remembered like Larderello, Italy, which hosts the world’s first geothermal power plant.

But the town itself is taking a wait-and-see approach, aware that these projects are likely years away from completion.

“What they’re saying sounds good,” said Kathy Ortiz, the town’s mayor, of the projects’ benefits. “But, it’s so early that we’re all unsure.”

A second life for oil wells

In May 2024, the Colorado Energy Office awarded $100,000 to Gradient as part of a grant program to support geothermal energy development. The award is to study whether a “geothermal energy network” could help heat and cool buildings in town and generate a small amount of electricity to boot.

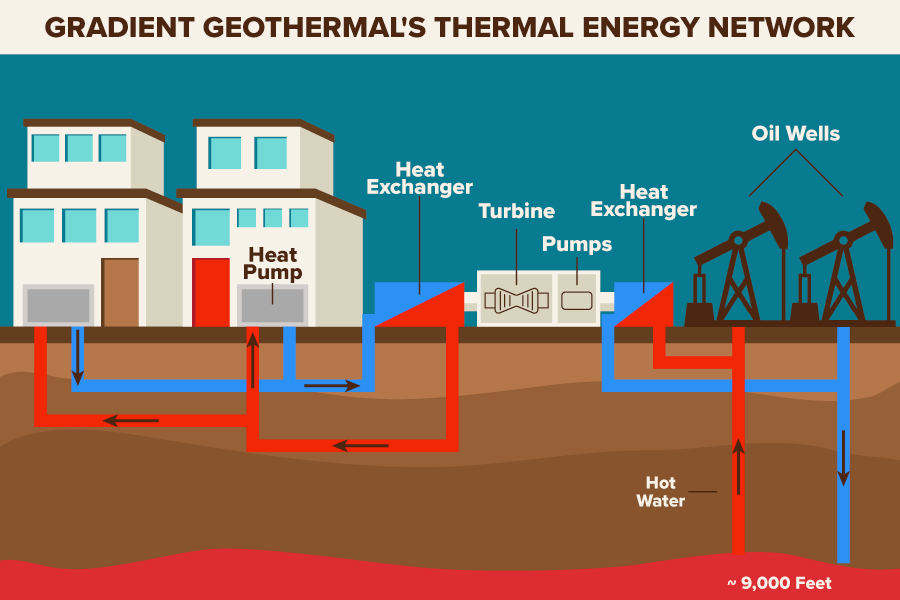

These networks use water to transfer heat from the Earth into buildings, a much more efficient and climate-friendly system than burning fossil fuels or guzzling electricity. Instead of natural gas boilers or air conditioners, these networks rely on geothermal heat pumps, which can heat and cool buildings in an all-in-one package. Plus, many buildings can be linked together to share energy, which makes the whole system more efficient.

Typically, these systems get an initial jolt of heat by running pipes hundreds of feet underground. That’s how it works across the state at Colorado Mesa University, for example. What’s unique about Gradient’s project is that the main heat source comes from hot salty water pumped up from oil wells that sink to around 9000 feet underground.

“Our goal is to take what ultimately is a waste product – which is heat waste – and turn that into a useful, beneficial use type of commodity,” Burke, Gradient’s CEO, said.

The wells in Pierce tap into the Lyons sandstone formation, a layer of thick, porous rock that stores oil and water. In the town of Lyons, Colorado, the formation juts out dramatically as sandstone cliffs. By the time it reaches Pierce, the rock is buried deep underground.

Gradient plans to one day reactivate several wells in town. The water that emerges to the surface will be around 240 degrees F. The company will first extract some of the water’s heat to generate a nominal amount of electricity. Then, Gradient will use more of the water’s heat to warm up a separate pool of clean water, to be used for a heating and cooling network. Finally, the salty water, now over 100 degrees cooler than when it was pumped, will be injected back underground to heat back up.

“There is the opportunity, like a second life for these [wells] in terms of geothermal,” Ostrum said.

Gradient is not yet ready to turn on wells — they are currently conducting a feasibility study that includes determining if the costs of heating and cooling pencil out.

The company estimates there are around 500,000 wells across the country that produce hot enough water to make some electricity and could be used for a geothermal energy network.

“ I do think there's a big opportunity for the town here, that I think we can replicate in other small towns and other oil and gas regions in the United States,” Ostrum said.

Electric power plant also in the works

McDaniel’s company, GTI, is further along. They received $1 million from the state’s energy office to drill into the Lyons formation to pilot a three megawatt commercial power plant — roughly enough to power around 2,500 homes for a year.

Geothermal power plants are typically located in places like Iceland, because they sit near tectonic plate boundaries that generate ample amounts of heat, and can spit up water close to 400 degrees F. But McDaniel said his company’s technology can make geothermal power feasible for other, lower-temperature water deposits around the world, which are often closer to power-hungry metro areas.

“There are no volcanoes in Denver, or Chicago or other places in the world where there are major population centers,” McDaniel said. “That’s the problem with conventional geothermal, it’s just not scalable.”

McDaniel said his company would be the first in the world to create a power plant that taps into what he calls a “hot sedimentary aquifer,” like the water sitting under Pierce. GTI wants to drill thousands of feet underground to tap into the Lyons formation. It’ll then pump that water up, extract its heat to generate electricity, and then inject it back down.

If GTI’s pilot works, McDaniel said they’d aim for much bigger power plants, which could power data centers or even cities like Denver. Unlike wind or solar, geothermal power can run all the time.

“It checks a lot of the boxes of what we need to have clean energy globally,” McDaniel said. “Solar only works when the sun shines, and wind only works when the wind blows.”

Seeking clean energy, but still tethered to oil

Under state law, Colorado is required to use 100% renewable energy by 2050. That shift is well underway, but oil and gas remain an important part of the state’s economy. Colorado is the fourth-highest oil producing state in the nation, and most of that crude oil is pumped in Weld County.

While Pierce’s wells are not producing oil, many residents still work in the industry elsewhere in the county, according to Ortiz, the town’s mayor. Rimrock Energy Partners owns a natural gas processing plant at the town’s edge, which also employs some residents.

“A lot of people in gas and oil, stay in gas and oil,” Ortiz said. “Money’s too good.”

M. Sue Spurgeon-Paris, a former mayor of Pierce, said she worked multiple roles in nearby oil rigs in the 1980s and 1990s. She said the alluring pay could paper over how dangerous the jobs were at the time.

“You work very long hours,” Spurgeon-Paris said. “It’s an ugly profession, and it’s dirty and it takes a lot of resources.”

Stephanie Malin, an environmental sociologist at Colorado State University who has studied the county’s fracking boom, said that some Northern Colorado residents living near “unconventional drilling” have reported chronic stress and depression after operators began setting up wells near their homes.

For Malin, the promise of emerging renewables like geothermal is that it can offer a fresh start from the oil and gas industry, and more equally share any potential economic benefits.

“It’s not perfect and every kind of renewable resource is different,” Malin said. “But in general, I think something like geothermal allows for a more stable economic sector than oil and gas production that is much more prone to exceptionally volatile global prices.”

“[Geothermal] can be something that communities can invest in,” she added.

A vision of the future

GTI aims to break ground on its pilot power plant six months after it finishes fundraising, and it has received all the necessary drilling permits. It’s one of just two companies in the state pursuing geothermal projects permitted to begin some form of drilling, according to the Colorado Energy and Carbon Management Commission. Developers for a geothermal power plant near Mt. Princeton have not yet received their drilling permits, according to regulators.

But GTI still needs millions of dollars to finance the project, which they hope will come in after they ink agreements with utilities and other companies to buy the power the new plant generates. Up to 40 percent of the plant’s cost qualifies for federal tax credits for clean energy projects, which could disappear in future Trump administration budgets.

For Gradient’s heating and cooling network, one of the main challenges is finding a series of buildings large enough to accept the heat. One promising candidate is a shuttered elementary school near a proposed pump station, which could be turned into a community center or other usable space. But because Pierce doesn’t own the school outright, the town would have to buy it and then renovate it.

In March, Ostrum presented an update of Gradient’s study to the town’s Board of Trustees, and said that the company likely needed the school and other buildings for the network to be economic. The presentation had videos explaining how geothermal energy networks worked, but the television wasn’t working, so trustees instead flipped through a printed PowerPoint with screenshots.

Trustees mulled the price of buying the building and turning it into something else, or demolishing it outright. Geoffery Broughton, a trustee on the buildings committee, wanted the town to take a big swing and at least try to repurpose the space.

“I think that it’s become popular to think that this is a community that has nothing going on, and that nothing good happens here,” Broughton said.

“So instead of us saying, ‘Oh poor Pierce, nothing good happens here,’ I think we were elected, we all chose to be sitting in these seats. Let’s take the opportunity to think forward, have a little bit of vision.”

Things are happening in Pierce. A Dollar General recently opened, and the town will soon get a new Mexican restaurant. Geothermal energy may be one of the industries that make the town money down the road.

Ortiz said it would be “cool” if Pierce is one day remembered for geothermal, because most people don’t know anything about the town. McDaniel said if their plant works, they might turn it “into a nice museum and offer tours,” which could raise the town’s profile.

But to Ortiz, the town’s allure is partly because it remains out of the limelight.

“We don’t have a stoplight, most of our roads are dirt,” Ortiz said. “We do like it small, and you’ll hear that from a lot of residents. They moved here because it was small and a country feel.”

Funding for public media is at stake. Stand up and support what you value today.