At a recent rally in Denver to protest the Trump administration, handmade signs vocalized worries for veterans, the elderly, immigrants, and other groups potentially affected by the president’s policies.

Standing in the crowd, Ben Wilson had chosen the message “Hands Off Medical Research” for his placard.

“I have a son that has a very rare genetic condition where only 300 people in the world have it,” said Wilson. “This administration, with cutting off medical research, is really affecting my son's ability for them to find cures for it.”

His two-year-old son Gabe has Bloom Syndrome. Among other things, the condition puts him at a higher risk of developing cancer.

Medical research is on the chopping block as the Trump administration looks to slice nearly $50 billion from the National Institutes of Health. In Colorado, NIH funds half a billion dollars in research each year.

In February, Colorado joined a lawsuit challenging the NIH cuts, which Attorney General Phil Weiser has called unlawful. A federal judge has temporarily sided with the states’ position and the administration has appealed.

For Wilson’s son Gabe, some of that research has the potential to be life-changing.

A loss of federal research funding is a “scary” prospect

At their home in Denver, the Wilsons keep their living room shades drawn because Gabe’s skin is sensitive to sunlight. It’s a common trait for those with Bloom Syndrome, along with a propensity for infections.

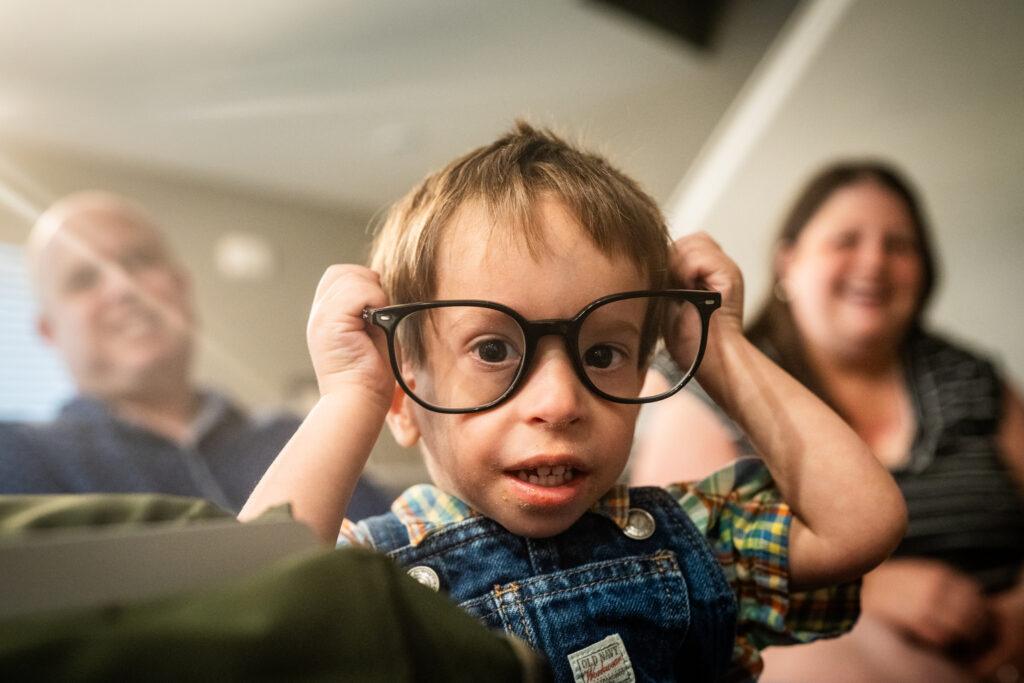

Gabe has brown hair and a warm smile. Sitting on the floor, he dug curiously through a CPR photographer’s bag, pulling out cameras, lenses, his phone - and his glasses, which Gabe promptly put on his nose.

“His personality is amazing and he's so sweet. And aside from his height, you would never know that he has anything wrong with him,” Alisa Wilson said.

Gabe has always been on the small side. He was born early at three pounds nine ounces and from the start struggled to put on weight. His parents would feed him, but he couldn’t keep it down.

“Ben always knew that there was something wrong with him,” Alisa said. “We weren't exactly sure, but vomiting constantly was not normal.”

Eventually, a geneticist tested Gabe, revealing Bloom Syndrome. The average life expectancy for people with the condition is 40 years. But, Ben said, any progress in heading off cancer might give Gabe more time.

“They're researching cancer vaccines, they're hoping to stop cancer from happening,” he said. “And with the cuts in NIH, we don't know if they're going to continue that research. And that’s very scary for a Bloom parent.”

“It’s a tough disease.”

Gabe’s care requires lots of doctor visits, tests and treatments. It’s been stressful and intense for the family.

This past winter, Gabe was down with a series of bugs from the end of December until February, a situation not uncommon in kids with Bloom Syndrome. It was one thing after another, including pneumonia and two bouts with fifth disease, which caused a rash to break out all over his body.

But by the time the family came into Children’s Hospital for a recent check-in, Gabe had bounced back. On the day of his visit, his tests came back normal.

Health providers keep a close eye on Bloom patients, screening them for cancer frequently and using antibiotics to keep them as healthy as possible.

“Any new things that he’s doing?” Gabe’s doctor, Michael Edwards, asked.

“We got two words now,” Ben replied. “He says, ‘I know.’”

That extremely toddler-ish phrase gave Edwards a hearty laugh.

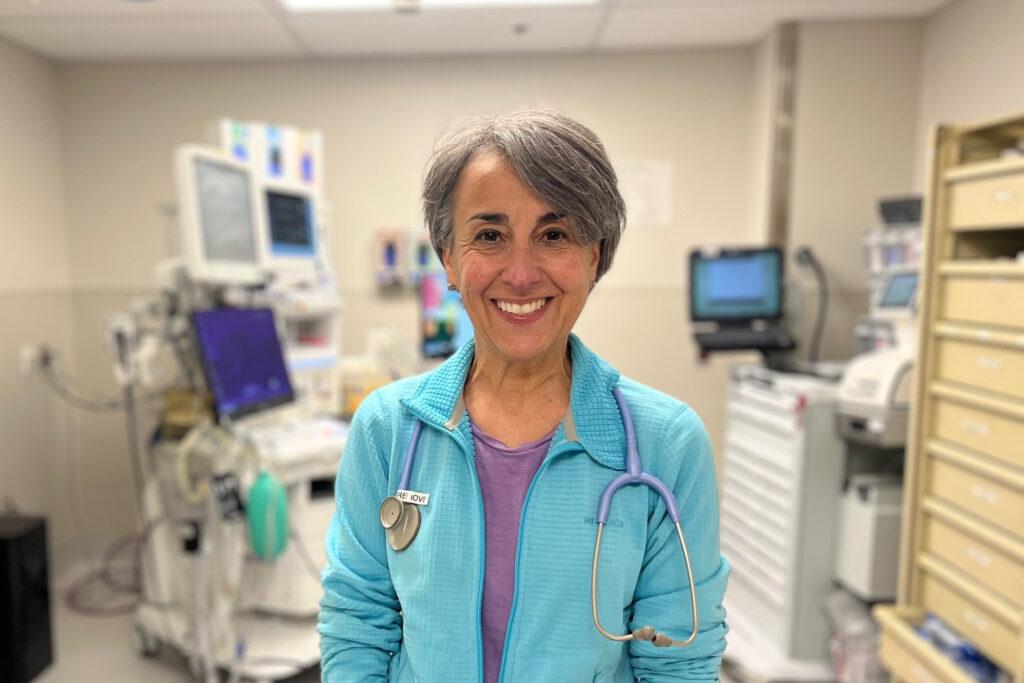

One of Dr. Edward’s jobs is to run the Cancer Predisposition clinic at Children’s.

Bloom Syndrome is “a tough disease,” he said. It causes people to be shorter than average, get recurring infections, have resistance to insulin and develop diabetes. That’s all in addition to the increased vulnerability to cancer.

“The most common thing we see is leukemia,” Edwards said, “but it could be a variety of cancers.”

Edwards balances his research work with days in the clinic, where he finds it gratifying to support families with kids facing these kinds of health challenges.

“I love getting to see patients like Gabe,” he said. “But then I also want to be able to go… the next day and work on a project that helps them in the future.”

The future for kids like Gabe Wilson depends on medical research taking place at the sprawling CU Anschutz medical campus and other research hospitals and universities across the country.

The prospect of that funding being reduced or cut off is discouraging to Edwards.

“I like to think that the thing we could all agree on is helping patients like Gabe,” he said. “It feels like (public) discourse is really difficult when you can't agree on something as simple as that, that you think we would all support.”

At stake, groundbreaking cures and promising medical careers

Fifty years ago, childhood cancers mostly weren’t curable. Today, they mostly are, thanks to medical research and clinical trials. And researchers have high hopes for the future, if funding continues.

“We are on the cusp of curing a lot of diseases that have never been cured before, not just in cancer, not just in blood disorders,” said Dr. Lia Gore, a pediatric oncologist who specializes in blood cancers and leads the hospital’s team working to eradicate pediatric cancers. “We're going to go backward with cuts in funding. There is no question.”

Doctors and nurses at Children’s Hospital Colorado treat patients with a wide variety of daunting conditions. Among the cancers and blood disorders they see are leukemias, malignant brain tumors, lymphomas, bone tumors, sarcomas, liver and kidney cancer and more than 150 others, with obscure names like Ataxia-telangiectasia and Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome.

Of the almost 300,000 kids Children’s Colorado sees from around the region each year, about 6,000 are enrolled in its Center for Cancer and Blood Disorders. The hospital is rated as one of the top 10 in the country for treating cancer.

The salaries of many physicians and other health providers at the hospital are supported, at least in part, by research grants.

Losing that funding, Gore warned, could harm the careers of young scientists and doctors like Michael Edwards. Plenty of researchers might move into another career or take a job in another country.

“There's a brain drain that goes on with that that you can't just make up for in the next budget cycle,” she said. “Because once those people leave the field, they don't come back.”

On a recent visit to the CU Anschutz campus, Rep. Jason Crow, a Democrat whose district includes the medical complex, said it was critical to keep medical research money flowing.

Federal grants fund “teams researching how to cure blindness, how to treat diabetes, how to stop the transmission of infectious diseases, just to name a few,” Crow said. “All of these things would be catastrophically impacted if some of the proposed cuts actually go through.”

Crow worries that a loss of that funding would severely damage the state’s ability to attract world-class health providers. “Coloradans will be directly impacted by the proposed cuts because we will not have that talent anymore if this happens,” he said.

CU Chancellor Don Elliman has warned that private philanthropy would not be anywhere near enough to replace lost federal research money if the administration takes drastic steps.

Funding for medical research is an idea that has across-the-aisle appeal, even among some fiscal hawks. In a recent interview with CPR News, Rep. Gabe Evans, the Republican representing Colorado’s 8th District, said, “making sure that we preserve and protect that research and the lifesaving medications and techniques that come from it is critically important.”

Evans said he has a child with unspecified “medical complexities,” and that his family has taken advantage of advanced medical research. Still, he believes there may be a way to get similar results with less federal spending.

“Whenever we talk about this, there's two sides to every coin, which is how much regulatory burden and how many hoops do these research entities have to jump through in order to be able to provide that life-saving research?” Evans said. “We have to make sure that we're being good stewards of taxpayer dollars.”

Also at stake, more than a billion dollars in economic activity and thousands of jobs

There could also be significant economic consequences for Colorado from a major loss of federal medical research funding.

United for Medical Research, a coalition of research institutions, patient and health advocates and private industry, estimates that the funding Colorado institutions get from NIH supports more than 7,000 jobs in the state and ultimately drives $1.56 billion in economic activity.

Last month, the administration announced a major restructuring of the Department of Health and Human Services, which includes NIH. The department cut some 20,000 full-time jobs, about a quarter of its workforce.

HHS Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. described the layoffs as part of his effort to refocus on areas of public health he considers the biggest concern.

"We aren't just reducing bureaucratic sprawl. We are realigning the organization with its core mission and our new priorities in reversing the chronic disease epidemic," Kennedy said in the news release. "This Department will do more — a lot more — at a lower cost to the taxpayer."

As the Wilsons wonder what’s next, they plan to keep advocating

Back at the Wilson home, Ben said it feels like everything is on the line right now.

“I was shocked when I saw the amount of cuts that they wanted to make to medical research and to the medical field. I was absolutely shocked,” he said.

The Trump administration, he feels, has shown it’s not looking out for kids with disabilities. “It's a scary situation to be in as a parent with a kid that has a life-limiting illness.”

He says he, Alisa, and other parents in their situation must make sure their message is loud and clear

“We just have to push back,” he added, noting their kids' futures may depend on it.

| This story is part of a collection tracking the impacts of President Donald Trump’s second administration on the lives of everyday Coloradans. Since taking office, Trump has overhauled nearly every aspect of the federal government; journalists from CPR News, KRCC and Denverite are staying on top of what that means for you. Read more here. |

Funding for public media is at stake. Stand up and support what you value today.