For nearly two decades, Bob Cone has wondered about the seemingly endless stream of coal trains he hears near his home in Larkspur. They amble southbound near Interstate 25, and he falls asleep to their wheels churning. Often, he’s waiting at an intersection for over a hundred train cars to pass.

“They’re hopper-type cars and you can see the coal piled up in each car,” Cone said. “Car after car, day after day.”

Cone wrote to our Colorado Wonders series to ask where all that coal is going, who’s using it and how much travels by rail.

The answer to his question is really a story about railroads, climate policy and changing economics.

Freight rail and coal go hand in hand

Burning coal for electricity first began in the United States in the 1800s. By the 1960s, power plants accounted for most of the country’s coal consumption.

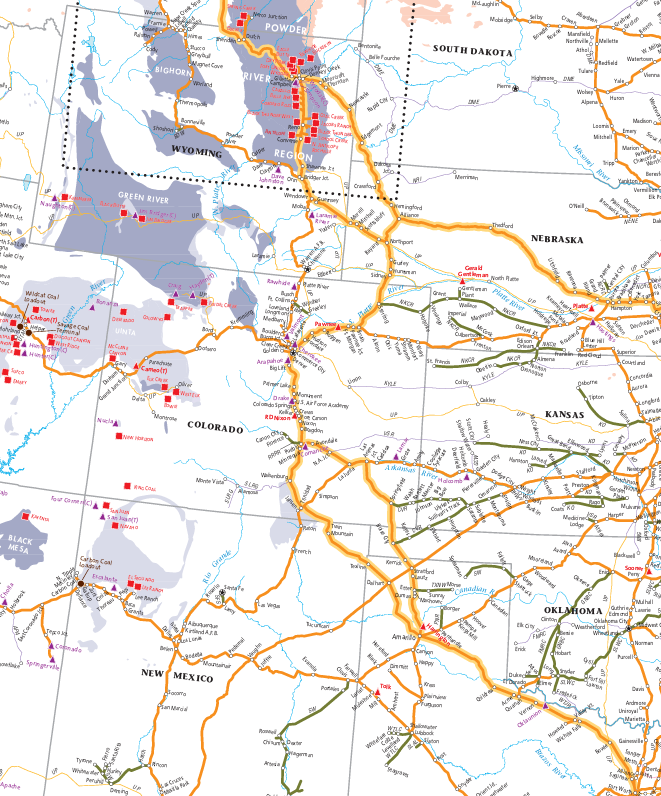

Coal production in the United States started in Appalachian states like Pennsylvania. But by the 1970s, vast coal deposits in Montana and particularly Wyoming — known as the Powder River Basin – transformed the area to a coal hotspot. Wyoming has produced the most coal of any state every year since 1986; in 2023, it produced 237 million tons of coal, by far the largest haul of any state.

Transporting that coal depends on railroads. Two legacy railroads — Union Pacific and Burlington Northern Santa Fe (BNSF) — move millions of tons of coal from the basin around the country.

Colorado also produces coal, mainly through Western Slope mines.

BNSF and UP handle most of Colorado’s freight, and they have lines parallel to I-25 that run through the Front Range. Most freight in Colorado is just passing through, en route to other destinations, according to state data. Between 2014 - 2019, coal was the top commodity by weight beginning, terminating and moving within the state, according to federal data.

But that’s rapidly changing.

Since 2009, there’s been a “significant decline” in coal traffic from Wyoming, according to the 2024 Colorado Freight and Passenger Rail plan. Industry projections and federal data show that the total weight of goods coming by freight rail through Colorado is expected to drop by 21 percent between 2020 to 2050, driven by sinking demand for coal.

“While coal once was a staple of railroads in Colorado, intermodal mixed freight, oil, auto, even grain, have really risen to fill those gaps,” said Jack Wheeler, president of the Colorado Rail Passenger Association, which advocates for passenger rail.

UP and BNSF declined to provide specific data of how many coal cars they move through Colorado.

Economics, not just climate policy, driving the move away from coal

While the U.S. has vast coal reserves, burning it to make power has significant downsides. It releases toxic plumes of mercury and emits planet-warming greenhouse gases when burned. Mining can ruin landscapes and cause diseases in miners.

Since 2005, coal consumption across the country has declined in most years, federal data show. In Colorado, the decline has been sharp. In 2012, the state consumed around 19 million tons of coal for electricity. But by 2024, that dropped to 9.6 million tons.

In January, just under a third of the state’s electricity came from coal — around the same as renewable energy. In the late 2000s, electricity from coal generated around 70 percent of the state’s power, according to federal data.

Will Toor, executive director of Colorado’s Energy Office, said the state’s climate goals are dovetailing with the rising costs to make power from coal.

“We’re now in the middle of this major transition away from coal,” Toor said. “Part of it is economics and then part of it is pollution.”

Burning coal in existing plants can be more expensive than building new wind and solar projects, according to Toor. Retrofitting old plants with equipment to meet newer, federal pollution standards is also shifting the country away from coal.

Colorado also has ambitious, legally-mandated goals for electric utilities to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 80 percent in 2030, compared to 2005 levels, and eventually to 100 percent by 2050. Those targets don’t mandate how a utility like Xcel Energy should achieve those reductions.

“But what we’ve seen is that essentially every utility has taken the same general approach,” Toor said. “Retiring their expensive legacy coal plants, replacing them with wind, solar and batteries, and then using [natural] gas generation … to make sure that you can keep the lights on 24/7.”

By 2031, all 10 remaining coal-fired plants in the state are slated to be snuffed out, according to Toor.

There are some bumps in the road. The Trump administration has quashed wind project permitting and cast doubt on climate change science. In April, President Trump signed an executive order to revive “America’s Beautiful Clean Coal Industry.” Tariffs could also push up the cost of solar panels, batteries and gas turbines.

“So there’s certainly some wildcards out there,” Toor said. “But the general trends toward shutting down coal and building the replacement generation is pretty clear,” Toor said.

Leaving on a Midnight Train to … Texas?

So with coal consumption declining, where is all that coal that Cone sees going?

“The trains that people see along the Front Range that are filled with coal are bound for markets south, typically Texas,” Wheeler, of ColoRail, said.

The market for coal is still huge in Texas, even though it’s declining. In 2023, Texas power plants consumed over 50 million tons of coal, and millions of tons came from the Powder River Basin via rail in Colorado.

W.A. Parish, an electric plant in Texas, sits on BNSF’s main coal line, which cuts through Colorado. In 2024, it carried over 3 million tons of coal from a single Wyoming mine.

“So more often than not, you are seeing coal trains go south from the Powder River Basin, and empty coal trains go north back to where the coal is sourced,” Wheeler said.

A single coal train can have 110 cars and be over a mile long, according to Wheeler. Depending on the model, one coal car can hold around 100 tons of coal. After some back-of-the-envelope math, it’d take around 331 full trains passing through Colorado to service W.A. Parish alone.

That’s just an estimate — BNSF declined to comment on the exact volume of coal rumbling through Colorado, but did say that the state is used to reach destinations like Arizona and Texas.

Power plants in Colorado also use coal from the basin. In 2024, the Comanche complex in Pueblo used over 800,000 tons from the “Black Thunder” mine in Wyoming.

Cone has been pondering this question for 17 years. Even though he now knows where the coal’s headed, it’s only a slight satisfaction, since fossil fuels are still heating up the planet.

“It seems like we should have evolved past burning things for energy at this point,” he said. “You’ve given me a little hope that the horizon does show a decline, and hopefully a complete cessation of coal for energy.”

Funding for public media is at stake. Stand up and support what you value today.