Early studies suggest psilocybin can help people with PTSD. But the VA doesn’t allow it. Will veterans be left behind?

By Haylee May

This story is part of The Trip, a CPR News series on Colorado’s new psychedelic movement.

Editor's note: This story mentions self-harm, graphic imagery of war and substance abuse.

Listen to an audio version of this story

The first day aboard his Navy hospital ship during the Vietnam War, then 19-year-old David Lyons was told to take items from a trough wrapped in butcher paper and throw them into the incinerator.

“I opened it up, and it was [part] of a guy’s arm,” Lyons said. “I was burning body parts. I literally said to myself, ‘Welcome to the war.’”

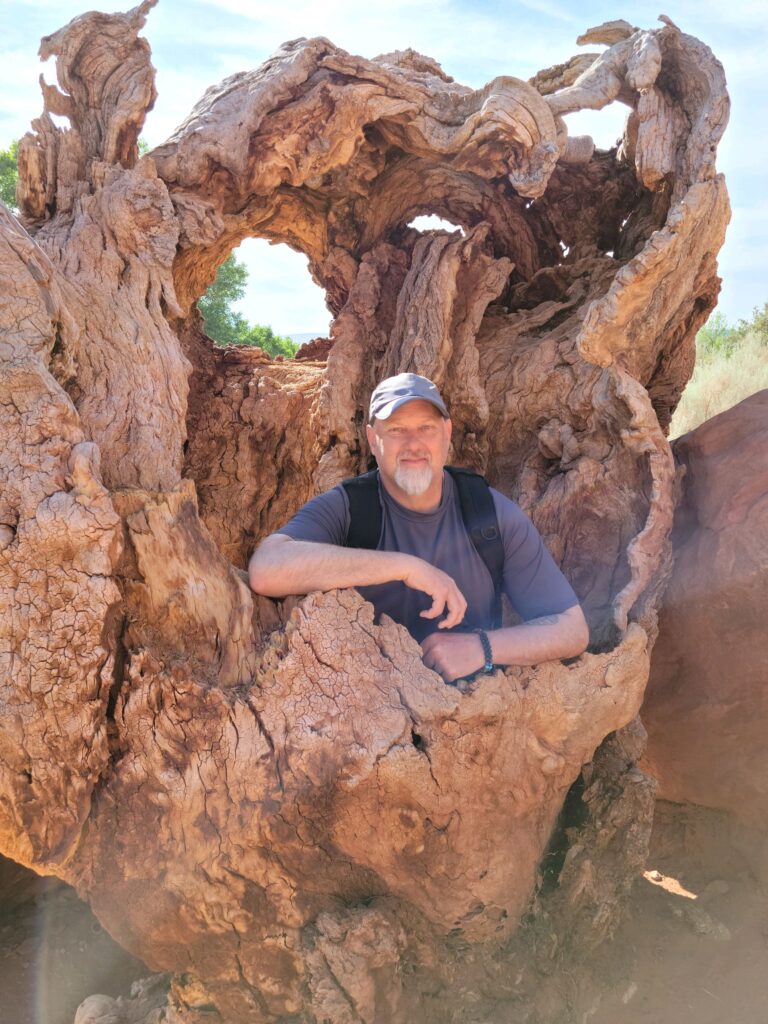

Decades later, a young man named Matthew Butler found himself deployed six times with the Army in Iraq and Afghanistan. The now-retired Army Colonel served more than 40 months in combat, earning a Bronze Star and other commendation medals before moving home to Utah. He’d joined to find a better life.

“Please understand that most people who serve in the military are not the bloodthirsty warmongers that you would think. A lot of us were preyed upon by a system. I made a decision at 18, and that decision landed me smack dab in the middle of a war."

Matthew Butler, veteran

Those deployments, thousands of miles and decades apart, resulted in similar consequences for Lyons and Butler

Both men, along with thousands of other veterans, are living with post-traumatic stress disorder.

But, just as their deployments differed, so too have their journeys to healing their mental health.

For Lyons, contemporary medicine offered by the VA worked, but not until years of self-medication pushed him to the brink.

Butler took an alternative path, one recently brought out of the shadows in Colorado: psychedelics.

Their two journeys illustrate why an increasing number of veterans are looking for solutions to their PTSD outside of federally legal medicines and why the VA itself is considering the possibility of psychedelics.

Butler and Lyons' experiences also illustrate the legal risks veterans face in seeking alternative treatments as well as the personal dangers they face while waiting for conventional treatment from the VA that some experts say is underfunded and understaffed.

Life in the aftermath of war

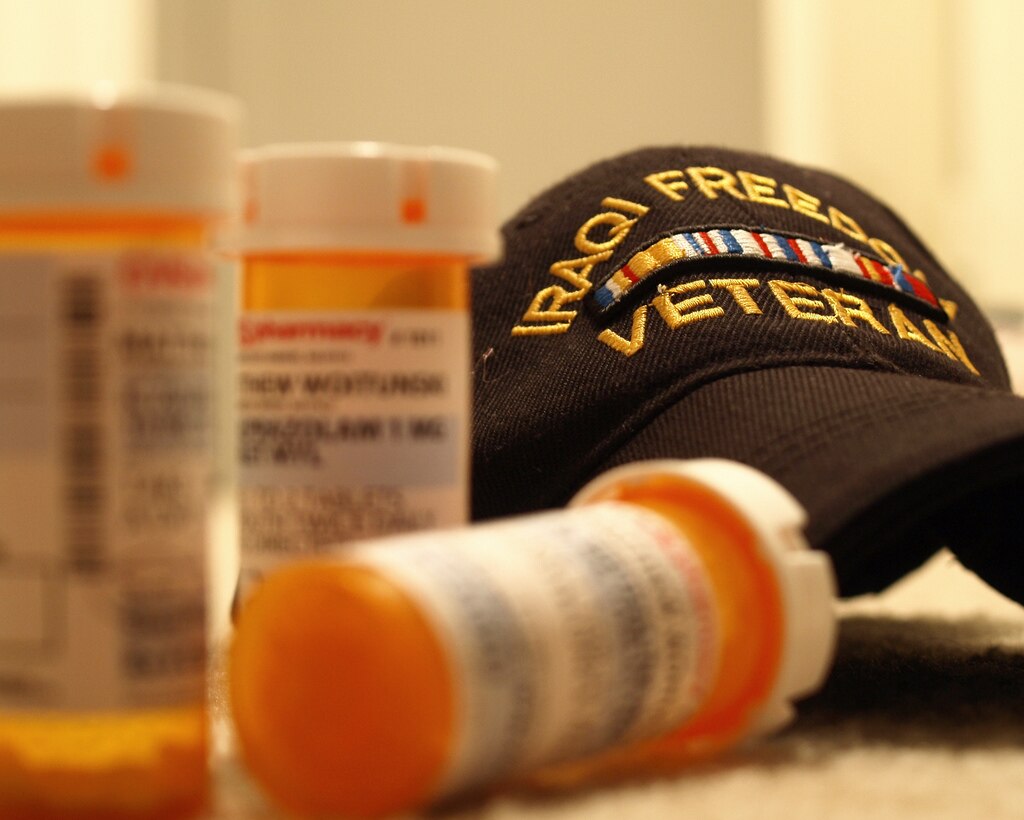

Traditional treatment for PTSD in veterans includes medications like serotonin reuptake inhibitors, often referred to as SSRIs, coupled with various types of therapy.

It can be a long and arduous process. Many service members give up.

“I'm on medication to help control what they call ‘The Nightmares,’” Lyons said. “We have night sweats, big time night sweats. The medication helps to keep some of that at bay. But there are things that trigger.”

He told CPR News he currently takes more than ten prescriptions: some for his PTSD, others for additional health issues, and more still to counteract the negative effects of those prescriptions.

“You're on so many medications that require other medications to handle the effects of being on the original medications, which makes it problematic sometimes for maintaining a job and lifestyle,” Butler said. “Sometimes, things just kind of tend to spiral out of control.”

Scientists, like University of California San Francisco Associate Professor of Psychiatry Josh Woolley, say current treatment can manage PTSD but, due to the chronic, relapsing nature of the condition, not cure it.

“We don't really have effective treatments for PTSD currently,” Woolley said.

“I always refer to antidepressants as a chemical lobotomy,” Butler said. “Sure, they take away my desire to commit suicide or they take away my pain and depression — but they take away everything else as well.”

An estimated seven percent of military vets will be diagnosed with PTSD in their lifetime, but the number who experience it is likely much higher.

“To get the guys to realize they have a problem, that's the hardest part,” Lyons said. “They don't want to admit it. They're going to say, 'Oh, am I weak then?' No, you're not weak. You just had a trauma that most people don't understand.”

Symptoms of PTSD include things like intrusive imagery, commonly known as flashbacks, or the brain’s way of trying to deal with a traumatic event by transferring the memory into a present experience; hypervigilance, a state of mind that causes people to constantly scan for potential dangers, even in safe situations; difficulty with trust; a negative self-view; and intense emotions.

Concurrent challenges: PTSD, anger and alcohol use

Lyons, who lives in Colorado, wasn’t formally diagnosed with PTSD until he retired at the age of 67. He was triggered while watching a movie with friends about World War II.

“All the time we were working, we were able to push it away, and once I retired, I didn't have all that to keep my mind occupied. And it surfaced,” he said. “My anger was totally out of control.”

Lyons turned to a coping mechanism readily available and legal — alcohol.

“I smoked and drank and hid it a lot. I mean, my sisters said, 'You're the strong one in the family. Now all of a sudden you're screwed up like the rest of us.'"

According to VA clinical psychologist Mandy Rabenhorst Bell, alcohol misuse and binge drinking are common among active-duty military personnel. She’s the program manager at Ascend Domiciliary Care for PTSD, a seven-week, live-in program in Colorado that treats patients with enduring symptoms of post-traumatic stress.

“What starts off being kind of an effective way to take the edge off, because physiologically [alcohol] does dampen our senses over time, becomes less effective and can itself become the problem,” Rabenhorst Bell said.

“I had the drinking like everyone else, driving in the car with a bottle and a sack, typical PTSD, but I didn’t know it,” Lyons said.

Loved ones pushed Lyons to get help from the local VA. After about a month of standard treatment, including medications and various therapies, he was recommended for Rabenhorst Bell’s program.

The program has limited occupancy and helps patients who are at “the most intensive continuum of care in terms of their need,” according to Rabenhorst Bell. In other words, they are out of options and need help now.

“They thought they were going to have a lot of problems with me because they said my anger was so palpable,” Lyons said. “It was just pouring out of me. And there were a couple of times I wanted to leave. It's the hardest thing I've ever done, but it's the best thing I ever did.”

Lyons credits the program with changing his life, offering support and companionship with other veterans. The program is strict, with mental health coursework, therapy, regulated medication, and the kind of daily structure many vets become accustomed to while in service.

“You're not alone. Somebody understands what you're going through,” he said. “I had a hard heart. People used to say to me I could whistle past a graveyard. That's how hard it was. Through the program, for the first time in my married life, I was able to cry with my wife.”

The new space can only hold up to 20 people at a time and requires patients to commit to the nearly two months of treatment. It’s a time commitment that’s not always possible for veterans with young families or those who work.

The program, while valuable, is an example of a common problem in veterans care — an effective treatment that’s limited in capacity and not accessible to everyone.

The challenges of accessing VA health care

Only 50 percent of veterans, around 9 million, are enrolled in VA health care or affiliated with a veteran service organization, leaving many of them to cope with the effects of their time in service on their own. Even those who are enrolled may not be getting the help they need.

Waitlists for VA mental health treatment often extend months due to a lack of available staff. This can lead to prescriptions for antidepressants before a therapy session can be scheduled in an effort to prevent veterans from engaging in other risky coping behaviors.

“The wait time crisis in the VA system remains our single biggest challenge,” Colorado Congressman Jason Crow, who served three tours in Iraq and Afghanistan, said. “When you're dealing with a mental health crisis, those wait times can be a matter of life and death.”

Crow blames the delays on staffing shortages and funding cuts.

The average wait time for new mental health patients at the Rocky Mountain Regional VA Medical Center is 43 days. Patients already in the system may wait up to 9 days for treatment.

While they wait, veterans struggling with PTSD symptoms like alcohol misuse and suicidal ideation are often prescribed gabapentin.

“Anytime someone is having a dysregulation in mood, which you see in PTSD, we use mood stabilizers,” Colorado psychiatric nurse practitioner and retired Navy Commander Cristi Bundukamara said.

But the use of gabapentin in this way has long been called into question, with multiple studies showing there is no clear evidence for its usefulness in depression or PTSD prevention. Medical professionals say it would likely be used less frequently if VA wait times were shorter.

When Butler was diagnosed in 2011 while still in service, he was immediately given prescriptions to cope.

“It's not like [prescription medications] are selectively removing depression or selectively removing suicidal ideation. It's removing your ability to feel. You don't feel joy, you don't feel happiness, you don't feel anything else. Your needle is stuck on neutral the whole time.”

Matthew Butler, veteran

According to the 2024 National Veteran Suicide Prevention report, suicide is the second leading cause of death for veterans under the age of 45. These deaths are often a result of untreated or undertreated PTSD.

“I kind of have mixed emotions about the VA,” said Butler. “On one level, I'm really grateful that it exists. I'm grateful for the benefits. And I know that they're up against some pretty big challenges. But then on the other hand, let's just be honest, it's a bureaucracy. It's trying to get your health care from the DMV.”

“The old style of treating chronic pain, mental health and traumatic brain injury is not working for our veterans,” Crow said. “They've been overprescribed medications to treat their [conditions], and it has absolutely resulted in veteran deaths.”

An alternative treatment: psychedelics

About the same time Lyons was being treated at Ascend, Butler was hitting his breaking point.

“The only way that I could get to sleep was through alcohol combined with opioids or sleeping pills. It says right on the bottle, ‘Do not mix these with alcohol.’”

He was following a conventional treatment plan of prescription drugs and therapy. But it wasn’t working for him and he fell into similar unhealthy coping mechanisms.

“In what world do we want to pretend that alcohol on any level is really that safe for somebody who is on that many medications and wrestling with those types of demons?” Butler said. “It's not. It's the least practical, least sensible alternative. Yet, it's the only socially acceptable, legal one. So that's where everybody turns. You learn to self-medicate.”

There was no program like Ascend for Butler in Salt Lake City. In 2018, he was arrested after an argument with his father turned violent.

“I made the decision in that jail cell. ‘When I get out, I am going to do whatever it takes to get a handle on this,’” he said. “Because the things that I was doing — the antidepressants, the group meetings, the counseling, all that — nothing was working.”

In 2021, he discovered something else: an ancient medicine that originates in the jungles of Peru called ayahuasca, a potent psychedelic not as easily accessible as mushrooms — or even LSD.

“A lot of people will tell you, ‘Well, that's a hell of a first step,’” Butler said. “I don't know that I'd necessarily advocate that everybody's first experience be ayahuasca, but that's how it unfolded for me.”

Butler found the opportunity to take the psychedelic in a group experience led by a shaman from Mexico in remote Utah. That moment was a turning point in his recovery.

“The biggest takeaway for me was being able to see life and the universe from that cosmic, eternal perspective — looking at the forest rather than the tree. If you have severe mental illness, such as complex PTSD, you have your nose pressed up against that tree. That's all you see, and your whole life is surrounded by just trying to cope day to day.”

Matthew Butler, veteran

After years of struggling, losing three marriages and families, Butler said the psychedelic treatments helped put him on the other side of that, and into “a wonderful, loving relationship.”

“I feel like I have a chance at a working, happy relationship with a spouse because I have the tools now to show up as the partner that I needed to be originally,” he said.

He now works often with psilocybin, both personally consuming it and leading fellow veterans through experiences as a shaman. He does that under the protection of the Religious Freedom Act and under the authority of the NaturalWorship church. He also offers shamanic counseling, microdose coaching, and help accessing ayahuasca ceremonies in Columbia. He says his goal now is to help people find their way to recovery like he did.

“You don't have to be a Green Beret with six tours under your belt to have complex PTSD,” he said. “It's not linear. It's not a comparison contest. Everybody has their own PTSD from life.”

PTSD changes the brain, psychedelics can change it back

Plant-based psychedelics, like ayahuasca and psilocybin, have long been used in indigenous cultures around the world for medicinal purposes.

“It really amplifies and allows our nervous system to begin to process and metabolize these traumatic experiences much more effectively than when we're in our ordinary state of consciousness,” Dr. Saj Razvi, the director of education at the Psychedelic Somatic Institute in Denver, where they train people to host psychedelic-assisted therapy sessions.

Dr. Saj Razvi, the director of education at the Psychedelic Somatic Institute.

A facilitator monitors a patient undergoing psychedelic-assisted therapy at the Psychedelic Somatic Institute.

The current consensus among scientists is that psychedelics help people overcome the trauma responses caused by PTSD through what’s called neuroplasticity, the ability for the brain to create or adjust neuropathways.

When someone has something like a panic attack, a neural pathway forms in the brain like a trail through the woods. That means it’s more likely that person will follow that trail through the woods again and will have a panic attack again.

The more it happens, the stronger the neural pathway becomes, and the cycle repeats itself. Early research suggests psilocybin helps patients change those ‘trails through the woods,’ helping them to find healthier ways of responding to and coping with traumatic memories.

“They're purposefully going there with the support of the therapist, with the support of the relationship, with the support of the medicine in particular,” Razvi said. “Then they get to process it there.”

The “reliving” of these events through a psychedelic “trip” can help the brain process the trauma and then let it go, allowing that implicit memory — the stuff that lives in our brains subconsciously — to clear and no longer cause the patient to return to the event unintentionally.

Patients experiencing psychedelic treatment will often have a physical response first. Their legs may move the way they did on the battlefield, or they may feel the pain from the injury that caused the trauma. In videos of psychedelic-assisted therapy shared with CPR News by the Psychedelic Somatic Institute, veterans were blindfolded and lying in a comfortable position on a reclined chair or couch.

Once a therapist can revive the memory, they’re able to guide a patient through a traumatic experience so they can begin to work through it. As patients relived the event in a therapeutic session with the help of psychedelics, some of their bodies began to mimic the movements of the memory, like running. Others began to shake.

The physical movement is the body’s way of letting go of some of the trauma being held both mentally and physically from their experience.

“The more they can have the reactions, the more they can process through this memory in this safe container, the less it will trigger them when they're walking around in a grocery store or when they're at breakfast with their spouse,” Razvi said.

Colorado is currently issuing licenses for what that state is officially calling “healing centers” specializing in psilocybin treatments with certified mediators, some of whom are professional therapists or psychologists.

Anecdotally and in early research, the treatment appears to be significantly effective for those living with PTSD.

A recent study published by the Journal of Affective Disorders found that military veterans with treatment-resistant depression, a common PTSD symptom, showed a 67 percent response and 58 percent remission rate after being treated with psilocybin after three weeks.

The experience is similar to multiple sessions of Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing, a Western psychiatric treatment often given by the VA where the patient briefly focuses on a traumatic memory while simultaneously experiencing sensory input, typically bilateral stimulation such as eye movements or auditory cues.

“That process is a way to instigate neuroplasticity in the moment,” Butler explained. “Then the therapist will introduce a traumatic experience, and we'll examine it from a different angle, which then allows us to put a positive spin on it. It's the idea that there are two sides to every coin. There are some of the negative things, of course, but then there's also maybe something positive that came from that.”

EDMR is typically given over the course of six to twelve weeks in weekly 60-90 minute sessions. One study from the 1990s showed 78 percent of veterans no longer met the full PTSD criteria after 12 sessions.

Butler said EDMR did help him find closure in one of his traumatic experiences. “It was one of those situations where really there was no way to view it as positive, but I was able to come away with the takeaway that I survived it. That was my positive takeaway.”

In his experience, psilocybin is able to accomplish the same thing, just more quickly.

“Whether it's through the therapists or even the plants themselves showing us these particularly traumatic experiences and then releasing the negative impacts and instead seeing the way that it fits into the big picture of our lives,” he said.

The current wave of psilocybin research for veterans began in 2017, when a survey of U.S. Special Forces veterans who received psychedelics in a clinical program in Mexico reported substantial improvement in PTSD symptoms and suicidal ideation after completion.

In December 2024, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs announced funding for a study on MDMA-assisted therapy for veterans with PTSD and alcohol use disorder.

Additionally, last year, an open-label pilot study administered psilocybin to 15 U.S. military veterans with severe treatment-resistant depression and co-occurring PTSD. At three weeks post-treatment in that study, 60 percent of participants showed a clinical response, and 53 percent achieved remission. These effects persisted in nearly half of the participants at 12 weeks.

Another active clinical psilocybin trial on veterans is happening now in Ohio.

Veterans value psychedelic therapy. But federal law stands in the way of safe, regulated use, despite the potential benefits

Butler is open about his use of psychedelics on his mental health journey because of a conversation he had with his 80-year-old mother after his first treatments.

“She said to me, ‘I don't fully understand the way it works, but what I know is that I got back the son that I sent away,’” Butler said.

“She saw the whole descent into the abyss. Just a bright-eyed kid just trying to make his way in the world, sucked into this war, somehow survived it; my descent into the madness, the PTSD, the addiction, the alcoholism, the suicide, the depression; then clawing my way back out of it through plants and coming out the other side.”

Matthew Butler, veteran

Butler began advocating for the use of psilocybin therapies in PTSD treatment in 2022. He believes outcomes for veterans could be improved if the VA began offering psychedelic treatment as an alternative to standard therapy and medications. But VA health care recipients — and the VA itself — are held to federal standards. That means they can’t legally engage in the use of, or prescription of, federally illegal drugs like marijuana, MDMA, or psilocybin, outside of sanctioned studies. All of those are considered Schedule I drugs according to the DEA under the Controlled Substances Act passed by President Nixon in the late 60s.

By speaking openly about his own use and the aid he gives others, Butler takes on obvious legal risks both federally and in Utah. He also risks losing his access to VA health care.

“I'm at an ethical crossroads here,” Butler said. “I can either continue to advocate and risk the consequences, or I can shut up and watch my friends die.”

Matthew Butler, veteran

Without access to these alternative therapies through VA services, Butler believes veterans will seek it through unregulated back channels like Reddit or Facebook Marketplace.

“There are several posts a day on all of them like, ‘Hey, does anybody have a recommendation on where I can find this?’ And I mean, how legitimate is that? That's where you create the safety concerns,” Butler said. “Veterans trying to navigate this space struggle to find reputable, trustworthy, ethical providers. People who are desperate, who are at the end of the rope, who feel like they have no other alternative because they've tried everything else out there and nothing is working. That’s where you’ve got to kind of navigate the swamp.”

Congressman Crow told CPR News that policymakers likely can’t do anything until there’s more data and evidence that the treatments work, but said he wants veterans to do what’s best for their mental health.

“Anecdotally I've talked to my friends who have suffered from chronic pain, and they've received treatment, and it has been life-changing to them and has saved their life and actually helped move them away from opioid addiction in some cases,” Crow said. “It's very promising, but we need good data; we need good information. And that needs to happen quickly because there is an urgency here of our veterans being left behind.

Psychedelics aren’t a “quick fix”

Still, doctors warn that even when done safely, psychedelic therapy is not a “quick fix” for PTSD, and it’s not for every patient.

“We tend to have a lot of magical thinking in the world of working with psychedelics. We have a sense that ‘Here's this incredible substance. It takes us to these very spiritual dimensions of our being’. But I think it's a little too easy to say, ‘Okay, take this, and then everything should be better.’ It doesn't work like that. It's not as simple as that. It's not a one-and-done thing. People go to their own personal hell, and they need to be held well in that space.”

Dr. Saj Razvi, director of education at the Psychedelic Somatic Institute

Razvi said it’s also important to note that not all veterans with PTSD will respond to psychedelic treatment.

“If somebody is taking a psychedelic to work with the most traumatic episodes that have happened to them at the same exact time their brain, their nervous system, is releasing these endogenous opioid chemicals, essentially what seems to be happening is that the [natural] opioid crushes the psychedelic response,” Razvi said, that means the session wouldn't achieve the goal of reliving and working through the trauma.

Patients using psychedelics like psilocybin on their own also risk causing complications with any ongoing treatments they get from the VA.

“There are some concerns with mixing [psilocybin] with serotonin reuptake inhibitors, which is the primary treatment for PTSD,” Bundukamara, who also operates the Mentally Strong clinic in Colorado Springs, which offers ketamine therapy to veterans alongside traditional treatment, said.

“The first-line treatment for PTSD is SSRIs, and [they] absolutely interact with psilocybin,” she said. SSRIs like Prozac can help treat symptoms of PTSD like suicidal ideation. “So, then you're asking the psychiatrist [at the VA] to come off of a med. If you've had suicidal ideations in the past, these are not light questions.”

Bundukamara has been on her own trauma and mental health journey. She has used ketamine, psilocybin, and ayahuasca to help treat her symptoms.

“Psilocybin is decriminalized here. We have lots of patients that are using it, and we have a really good understanding of that interaction with your medication,” she said. “How many experiences should you be doing? How often should you be doing this? So we can educate as part of that process of a psychiatric evaluation and treatment.”

Like Butler, she also has concerns about how veterans are using psilocybin due to a lack of legal access and says they could be overestimating the dosing.

“We have serotonin receptors in our heart, and we can actually cause fibrosis in the heart if [we’re] using too much psilocybin,” she said. “So this is my concern with my patients who are microdosing every day.”

What’s next? FDA approval for psilocybin therapy

In order for psilocybin to be treated as a legal, prescribable drug, the FDA would need to approve it, just like any other regulated medication.

In 2018, the agency designated psilocybin as a "breakthrough therapy" for treatment-resistant depression, which often co-occurs with PTSD. The move acknowledged the drug’s potential and is facilitating expedited research.

“There's promising data that psilocybin therapy can be safe and effective for depression, but it’s still pretty early in a lot of ways,” Woolley said. “Typically for any new drug, you have three large trials, but if you have breakthrough status, like psilocybin, you might be able to have just two trials.”

The designation means that, for the first time since the 1980s, the federal government is taking clinical trials seriously for psychedelic treatment of a range of mental health disorders. All of them are aiming to quantify whether these treatments are safe and effective.

“That's a difficult thing to figure out,” Woolley said. “It takes time. You have to study it across sites and across different demographics. And so there's a lot of work that still needs to be done.”

Two companies, Compass Pathways and Usona Institute, are currently working on second trials. Still, advocates are cautious. There was similar anticipation when the FDA considered approving MDMA as a treatment for PTSD. The agency rejected the therapies and asked for more data.

“Those results are not out. So I wouldn't say that even for depression, where we have the most data, that [FDA approval] is a done deal,” Woolley said.

Woolley and one of his fellow scientists at UCSF recently published a review of all the current data and knowledge surrounding psychedelic-assisted therapy for the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. The publication reflects the VA's broader commitment to researching psychedelic therapies.

“There was a lot of fear about having your patients use cannabis 10, 15 years ago because we didn't know how it impacted,” Bundukamara said. “Now, the research is coming clearer.”

But after more than 10 years of legalized cannabis, there is still no federal approval. It’s unclear what that could mean for psilocybin.

Psilocybin treatment puts VA benefits at risk, but many find the risk worth the reward

To lose VA benefits after using psilocybin, a veteran would need to be charged. “You can lose your benefits as a felon,” Butler said. “However, I've been told by several [members of] law enforcement that unless you're out there being brazen about it, they’re not going after the average daily psilocybin microdoser.”

Additionally, Bundukamara said the VA is not screening its enrollees for psilocybin use. “The VA is not testing for those substances. They are, however, starting to test active duty military,” she said.

While it is unlikely that a veteran who uses psilocybin at a healing center or elsewhere to treat their PTSD symptoms will be investigated for a crime unless they’re distributing the drug, Rep. Crow still believes it’s an unfair choice.

“It is unacceptable to put veterans in that position of risking losing benefits and care to seek what they believe that they need to be well and to be healthy and to survive. I always tell my fellow veterans, nobody knows what you need more than you, so get the care that you need, seek the treatment that you need.”

Rep. Jason Crow

Lyons, who has not used psychedelics himself, agrees.

“Even [if] it’s legal in Colorado, it's still a federal offense. And I think that's wrong,” Lyons said. “I think with the psychedelic treatments, if studies start seeing results — it's too early right now to say anything — but whatever works, works.”

Regardless, Butler believes veteran psychedelic use is here to stay.

“We'll never turn that clock back,” he said. “There'll always be a demand, and the demand is growing. So, as long as politicians stand in the way of above-board white market plant medicine, then it's going to stay below board.”

Story by Haylee May

Visual guidance by Hart Van Denburg

Edited by Alejandro A. Alonso Galva, with the help of Megan Verlee, Chuck Murphy and Carl Bilek

Produced by Lauren Antonoff Hart

CPR Reporters Dan Boyce and Caitlyn Kim contributed reporting.