It was always Charlie Burrell's plan to move to Colorado. The kid from Detroit loved the mountains and wanted to live in Denver, the place his mom was born. It was also the bassist's dream to play with the San Francisco Symphony.

Both dreams he accomplished handily.

Burrell was given the title, "the Jackie Robinson of music." Though he may not have been the very first Black musician to play with a major American symphony, being the first Black member with the Denver Symphony Orchestra in 1949 enshrined him as a pioneer.

He was also the last surviving musician to play Denver’s historic Rossonian Hotel, which helped earn Five Points its legacy as the “Harlem of the West,” an important and safe place for Black America when the city and nation were still segregated.

Burrell died early Tuesday at 104 years old.

He played bass with the Denver Symphony for 10 years, before becoming the first Black member of the San Francisco Symphony. Burrell's pioneer essence was also felt in education. He was one of the first professors of color at the renowned San Francisco Conservatory of Music.

He stayed in the Bay for five years, before an earthquake sent him back to the Rocky Mountains and the Denver Symphony. While he was playing with the Denver orchestra, he played with jazz bands and other notable musicians like Charlie Parker, Billie Holiday and Ella Fitzgerald, among others.

Burrell said the symphony salary wasn’t enough to make ends meet to care for his four kids, so he took other jobs, including time as a plumber and an auto worker.

In an interview with CPR News last year, Burrell remembered a summer he spent painting linseed oil on every seat at Red Rocks Amphitheater.

“That was my job,” Burrell said. “To resurrect those seats. It took me three months.”

Some days after a tough, hot day at Red Rocks, he would have a concert that same day. He said Red Rocks is a special place, in part because the acoustics are unmatched.

“The best in the world. You can't believe it. Mother Nature did it,” Burrell said.

His time as an educator set him up to be an effective mentor to young musicians, such as the legendary bassist Ray Brown. He also worked with his niece, Dianne Reeves, who is a multi-Grammy award-winning vocalist.

Burrell played with the Denver orchestra until he retired at 79 years old in 1999.

Retirement didn’t mean much in terms of how much music Burrell played. He played with the Charlie Burrell Trio and played music with his musical family.

He was given the Martin Luther King Jr. Humanitarian Award in 2015 and in 2017 he was inducted into the Colorado Music Hall of Fame.

In 2019, for Burrell’s 99th birthday, the Colorado Symphony performed Tchaikovsky’s 4th Symphony — the same piece that inspired Burrell to pursue a career in classical music.

"Charles dedicated his life to his music and inspired the world with his bass. As one of the first African Americans to win an audition with a major symphony orchestra, he opened the doors for musicians of color everywhere," his family said in a statement Tuesday. "While we are heartbroken at his loss, we are also thankful for his long and inspiring life."

Burrell began playing the bass and the tuba at 12 years old. Burrell told CPR news in 2024, that when he started playing the bass, the instrument was bigger than he was.

“I had to stand on two Coca-Cola boxes to reach the top of the instrument,” he said.

Burrell didn’t like to speak about racism he encountered in the music world, though his family said he endured plenty.

After junior high, he went to Cass-Technical High School in Detroit, one of the top music schools in the country at the time. Burrell's first teacher reluctantly accepted him as a student, and would go as far as to teach him incorrect techniques. He said it took him more than four years to correct.

“I didn’t get angry, it was just another one of those things that you get over and learn from and move on,” he told Andrew Hudson, a longtime jazz musician who wrote a mini biography of Burrell.

While Burrell studied classical music, he played jazz in his spare time with his friends. Going as far to play with a jazz trio in 1939, alongside Billie Holiday at the Three Sixes lounge in Detroit.

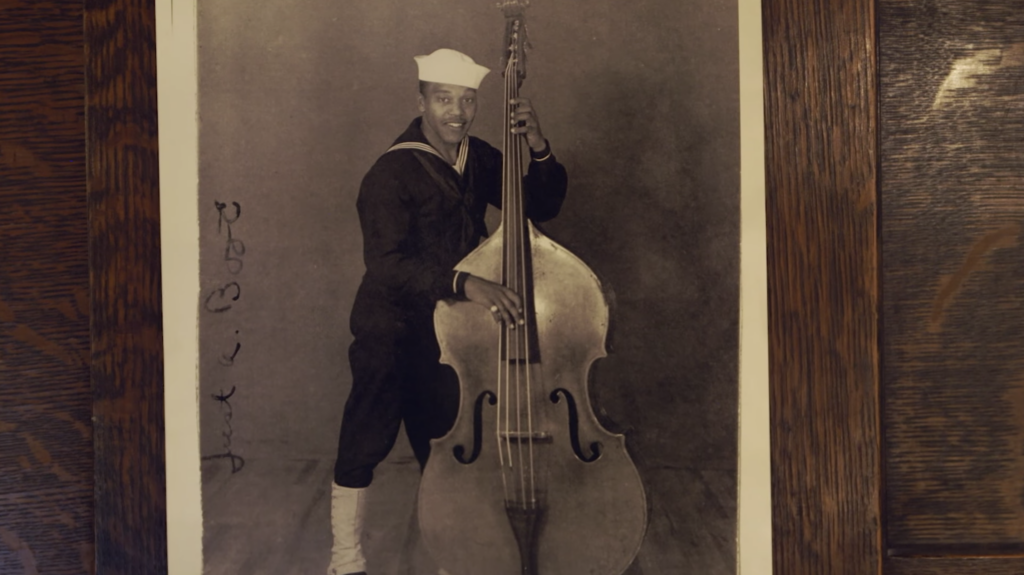

In addition to his many accolades, Burrell was a World War II veteran. He enlisted in the U.S. Navy and was stationed at the Great Lakes Naval Base in Chicago. He was selected to join the first all black Navy band and played alongside greats such as trumpeter Clark Terry and trombonist Al Grey.

He also took advantage of the nearby Chicago Symphony Orchestra and Northwestern University to continue mastering classical bass.

Following his honorable discharge from military service, Burrell was refused auditions with four different symphonies, and ended up in Denver in 1949. He was a janitor at Fitzsimmons Army Hospital and a student at the University of Denver when he met John VanBuskirk, the principal bass player at the Denver Symphony, on a bus.

VanBuskirk managed to get Burrell an audition, and the rest is history.