Owen Martin has a simple remedy for anyone who doesn't believe fireflies live in Colorado.

The University of Colorado Boulder Ph.D. student arranges visits to the places where he studies the bioluminescent insects. On a recent evening, he led an expedition to a marshy meadow near Boulder Reservoir, where the beetles rose from tall grasses after a series of afternoon thunderstorms. As lightning pierced the horizon, the bugs first blinked, then traced longer arcs of light into the fading dusk.

“If you pay a bit more attention, you find things like this all over the place,” Martin said. “It’s one of those things that give me a lot of hope and joy and makes me happy to be alive.”

Lampyrid beetles — better known as fireflies or lightning bugs — are far more widespread in the Midwest and eastern U.S. Along Colorado’s Front Range, however, the bugs emerge from their larval state to mate for only around two weeks in late June and early July around the region’s scattered wetlands.

Those fragmented populations could be especially vulnerable as insects struggle worldwide. A recent analysis found global firefly populations have declined due to habitat loss, light pollution and pesticide usage. Martin fears similar forces could forever darken Colorado’s firefly hotspots at a moment when scientists have only started to unravel their mysteries.

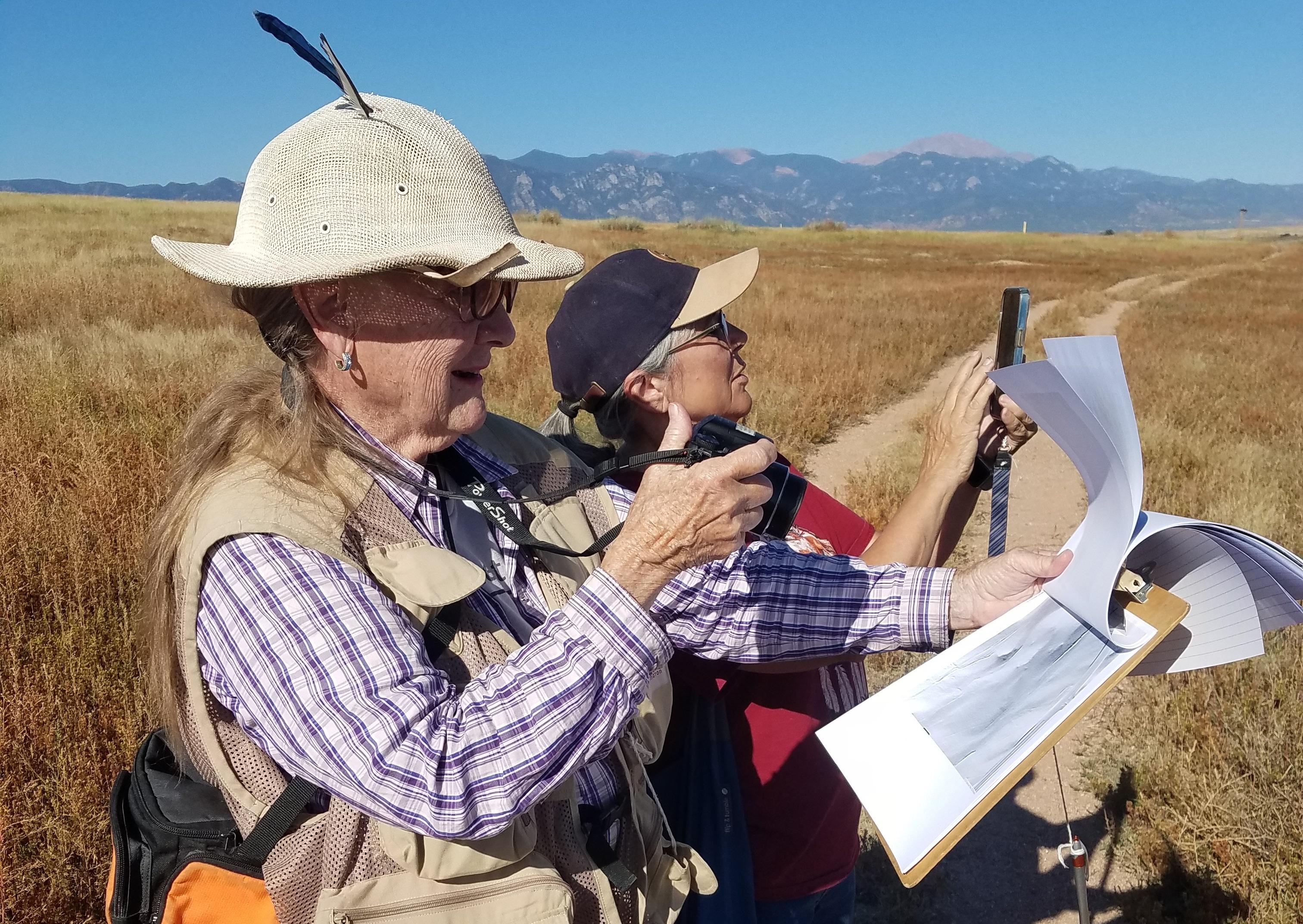

His current project has enlisted citizen scientists to capture detailed images of evening firefly scenes. In the process, he hopes to not only learn more about the elusive creatures but also parse out what, exactly, they’re blinking about.

Speaking firefly

One of Martin’s volunteers arrived by e-bike early in the evening. He set two GoPro cameras on stands facing the meadow, and then used a tape measure to record the distance between the two devices.

The procedure will let Martin later create a 3D map of the firefly blinks unfolding over time. It’s an ideal data set for his lab, which works at the intersection of computer science and biology to study animal communication.

Orit Peleg, Martin’s adviser and an associate professor of computer science and biophysics at CU Boulder, developed the recording method to study synchronous firefly populations. In places like Tennessee's Great Smoky Mountains and South Carolina’s hardwood forests, the beetles sometimes flash in unison, and scientists are just beginning to understand the "algorithm" the bugs use to coordinate the dance, Peleg said.

Colorado’s fireflies don’t synchronize, but Martin says their blinks still follow predictable patterns to attract mates. The bugs are a part of the Photuris genus, a category known for its talent as a mimic. Researchers have even observed some Photuris females in other locations imitating the flash patterns of another type of firefly. The carnivorous insects then devour males lured by the trickery.

“Watching many populations, you see much more of a repertoire or vocabulary each species has,” Martin said. “There might be much more being said than just looking for love.”

Categorizing Colorado’s lightning bugs

Martin’s research also aims to identify the exact type of fireflies living in Colorado and pinpoint their favorite habitats.

At the wetlands near Boulder, the Photuris fireflies have a flashing pattern different from related bugs living further east. Other populations found on Colorado’s Western Slope blink their own sort of Morse code. Due to those differences, scientists have long suspected Front Range fireflies are a distinct species, but the broader scientific community has never confirmed the hypothesis.

A recent genetic analysis conducted by Martin adds weight to the idea. It builds on earlier research conducted by Tristan Kubik, an entomologist at Colorado State University, who has even proposed a scientific name for Front Range fireflies: Photuris coloradensis. The duo is now working to gather funding for a more detailed investigation.

“We have every intention to push that extra genetic work forward,” Kubik said.

At least five firefly species found across Colorado over the last century are held as specimens at the University of Colorado Museum of Natural History. The far most common variety, Pyropyga nigricans, love to live in irrigated lawns but don’t flash at any point of the year.

Martin has already developed software to identify fireflies based on their flash patterns. Once it's widely available, he hopes conservationists will use it to identify Colorado fireflies and protect their isolated, wetland habitats.

“Insects are not humans' favorite, but fireflies do this to people. They make people feel these wonderful feelings you can kind of channel and tap into and get people excited to protect the land that we live on,” Martin said.

Breeding a backup population

Other firefly fans aren't waiting for comprehensive population studies to safeguard the species.

A short drive south of Boulder, Francisco Garcia Bulle directs research and conservation for the Butterfly Pavilion. In 2017, the nonprofit insect zoo started capturing lightning bugs in Fort Collins to support a breeding program that might someday allow conservationists to reintroduce hundreds at a time.

It's not an easy task due to the lifecycle of Colorado's blinking firefly varieties. On a shelf, the Butterfly Pavilion has male and female fireflies sealed in what looks like plastic takeout food containers filled with soil and a plastic plant.

Once the insects breed, their eggs will hatch into larvae, which crawl through the soil like far flatter versions of pillbugs, better known as rolly pollies. Only after two to three years will the bugs pupate into sexually mature fireflies.

Bulle said his staff has managed to produce just five fully developed lightning bugs over the length of the project. One female firefly emerged earlier this year. A technician named her Georgia, and she’s now held in a container with five males captured near Fort Collins to breed and lay eggs.

Her offspring would represent the first time one of the captive-bred fireflies has reproduced over the course of the project. It’s slow progress, but Bulle says the Butterfly Pavilion could accelerate the process with more staff time and funding resources. In the meantime, he plans to continue honing the art of firefly husbandry to help ensure the state’s lightning bugs never blink out for good.

“We can already hatch them and keep them healthy enough to become adults. So that's already a huge step,” Bulle said.

Editor's note: This article has been corrected to clarify the range of firefly species in Colorado.