Writer Jim O'Donnell lives in Taos, New Mexico. But he's a Pueblo native and grew up playing in Fountain Creek. At the time, it was often dry, and playing in Fountain Creek is not something one would want to do these days.

O'Donnell has had a lifelong dream of following the path of Zeublon Pike. But the siren song of the Fountain had other ideas.

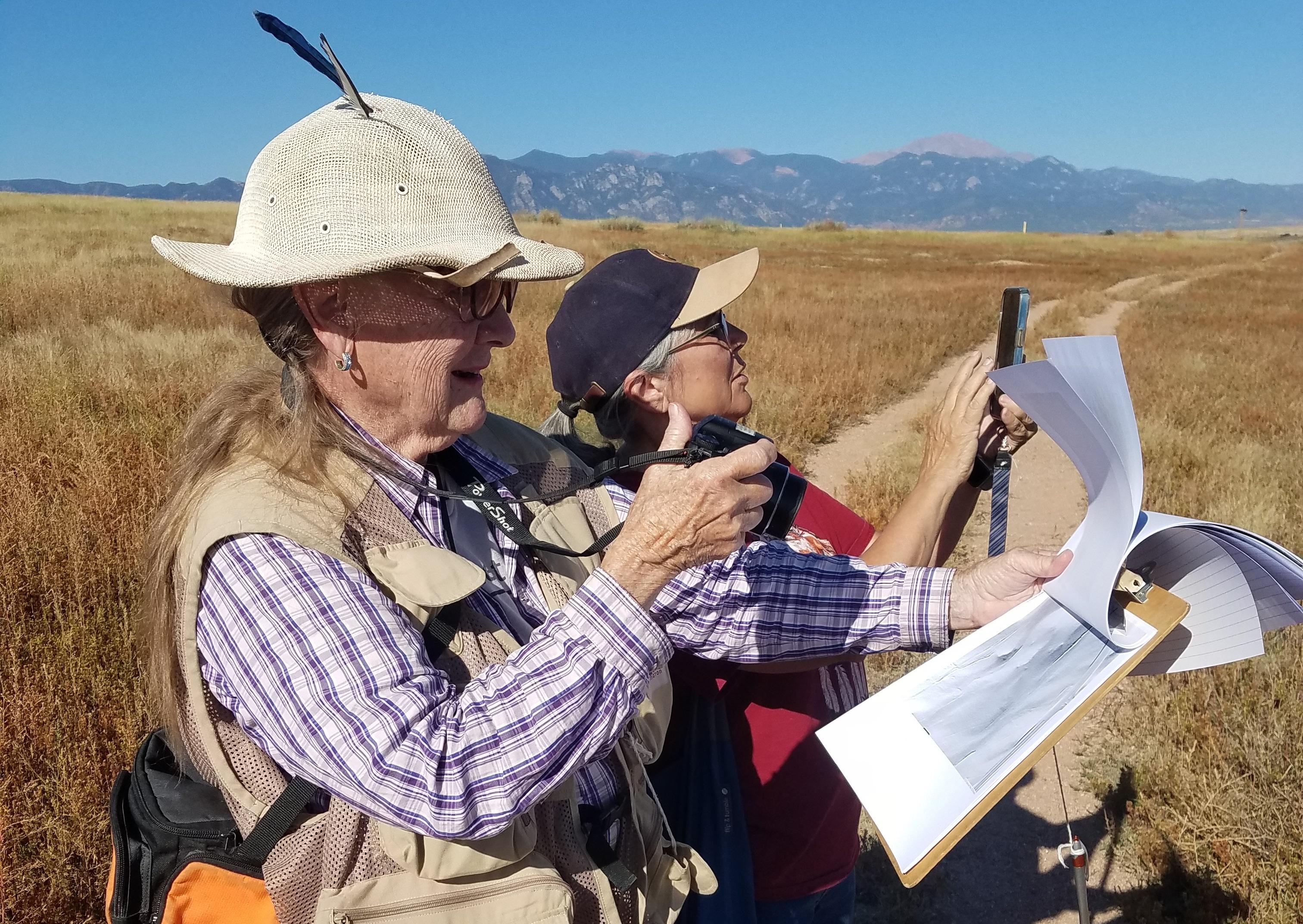

He wrote a book called Fountain Creek: Big Lessons from a Little River. It was released in November and quickly became a favorite for readers in Colorado. He recently met up with KRCC's Andrea Chalfin at Clear Spring Ranch Open Space, just south of the city of Fountain, to talk about it.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

KRCC's Andrea Chalfin: What brought you to this? The Fountain Creek?

Jim O'Donnell: I'll try to keep it somewhat short, but I grew up literally playing in Fountain Creek when we were kids. We used to ride our bikes down there, and I have to say there was no water in the creek in those days. So in the 70s, early 80s, and you would get those flash floods and occasionally a trickle down, but largely the Fountain Creek was dry.

And so we'd go down there, ride our bikes, and then later, when I got into high school, it was where a lot of us we went down there and built bonfires and drank.

So I have this long history with the creek, and I also noticed along the way, especially after I left home and I went off to college, and then I lived in Europe for quite a while and traveled around and every time I came home, I just noticed there was more and more water in Fountain Creek. It was kind of just one of those things I noted and I saw and I remarked on it, but didn't really stand out for me as a question so much for quite a long time.

And then right around the year 2000, 2001, somewhere in there I kind of started thinking about, Hey, wait a minute. Why is there water in the creek all the time? Something's different now.

This would be a really interesting story about how we relate to water and what kind of changes do we make that impact our water systems and how do we interact with and treat waters?

How do we view them? I thought the Fountain really kind of exemplified a lot of these big questions.

Chalfin: Talk a little bit about the path of the Fountain.

O'Donnell: So where does the Fountain begin, right? I think that's kind of just a fun question for watershed managers, hydrologists and more scientific folks. The highest point in the watershed tends to be where you label the start of the watershed. So in that sense, we think of Fountain Creek as starting basically on Pikes Peak.

But what's fun about the Fountain is that it has other sources, right? Really, I mean, in some ways, the source is kind of Monument Creek and it's the main tributary to the Fountain.

But really, if you just walk up the Fountain all the way, which I have at this point, you basically end up in the gutters of Woodland Park.

Chalfin: We know that the Fountain collects all of Colorado Springs' stormwater, runoff, wastewater, all of that gets put into the Fountain and carried down into Pueblo. You write in the book that there was a time when Pueblo wanted to use the Fountain as a source for water, but they found out they couldn't.

So if you're not going to use the water as a source for agriculture or drinking or what are you going to use it for? It kind of makes sense, don't you think, to put garbage, for lack of a better term, to use it as a way to get rid of the wastewater?

O'Donnell: I just want to challenge the assumption of your question. Do we need to use the Fountain for something? Are our rivers just resources? And one of the questions that is kind of fundamental to the book for me is the question, how do we define a river?

And I don't have a firm answer for that, but is it just a trashway? Is it just for municipal water? Is it just someplace to put our effluent? Or does a river have different values beyond that?

And I think I can hear somebody listening to this going, "Oh, these hippies." But I think it really begs the question: does everything have to be a resource? And of course, I would argue no. A river has value beyond what we humans place on it as a resource to be exploited.

Chalfin: You spend a lot of time in your book, there are a lot of motifs that keep popping up: things like shopping carts in the Fountain, things like needles in the Fountain, and certainly homeless encampments. Why was it important to you to bring up that imagery repeatedly throughout the book?

O'Donnell: One of the goals of this book is that I really wanted to give, as much as I could, a rounded picture of the Fountain watershed. And one of the striking things about the Fountain, whether you are in Pueblo or Colorado Springs or Manitou, is the number of human beings that are living by the creek.

And they're homeless, they're unhoused individuals. And I just felt like I could not write a book about this watershed without that because I wanted to give an accurate picture. And one of the values of this watershed, one of its uses, is kind of a dumping ground for people who do not have housing in this society.

I spent a lot of time talking with and interviewing homeless folks by the creek and understanding what their lives were like. And I really came away with the sense that the way we treat this creek as just something to be utilized and thrown away and exploited in one way or the other, reflects the way that we treat other human beings in our society, the folks that are unhoused.

That's why that motif kind of shows up again and again.

For one, it's just accurate reporting; this is what I'm seeing. But for two, you've really got to understand that in this modern day of age, you can do nature writing, but it's not just about, oh, the tree's so beautiful and the flowers are so beautiful. It's about what really is happening in this system.

Chalfin: The book is certainly about Fountain Creek. But is it really? Or is that just a vehicle to talk about other things?

O'Donnell: I think so. In some ways. Yeah. I mean it's twofold. One, I really wanted to write something about this creek because this is a complex, fascinating little water system that nobody knows about and nobody's written a book about it before. This is really the first book. So I wanted to have something that was about Fountain Creek.

But yes, your question is right. I've called Fountain Creek the poster child of the Anthropocene. And I realize that this term that we've come to be using over the past 20 years, Anthropocene, is problematic in and of itself for a variety of reasons.

Chalfin: And define the Anthropocene?

O'Donnell: So the Anthropocene is basically this geologic age where humans dominate the entire global system.

It's not an official term, but I think it does work to kind of encapsulate some of this moment that we're living in history. And so in that sense, if the Fountain is the poster child of the Anthropocene, then what is it showing us about the other actions that we're taking — be that urban planning or dealing with climate change or creating protected areas?

What are the larger lessons of this creek? And so I think one of my goals was for this not to be just a Colorado-specific book, but a book with larger lessons, especially for the entire Western United States, but even worldwide.

Chalfin: The Fountain runs from Woodland Park through Manitou, Colorado Springs and down into Pueblo. And as you say, a lot of the problems that Pueblo has with the Fountain are because of the actions in Colorado Springs. It struck me in the book that Colorado Springs is kind of a villain here. You villainized it a little bit. How do you think about that? How would you react to that?

O'Donnell: I think I would preface this by saying that there have been a lot of changes in Colorado Springs government, positive changes, and there has been a lot of positive changes over the last 10 years, maybe even a little longer in Colorado Springs Utilities. I mean, there's really good people working there, and they have started to shift their bureaucratic culture toward the right direction, I think. So I definitely want to get kudos out there to a lot of the folks at Colorado Springs Utilities and in the government of Colorado Springs, some improvements.

But yes, Colorado Springs has kind of been this odd city out in terms of Colorado in general, because Colorado Springs does not have its own real water resource, right? Again, it has to import 80 percent of its water from another basin, literally on the other side of the state and across the mountains. So otherwise, Colorado Springs simply could not exist. And then you've got the situation of Colorado Springs also couldn't exist as it does without enormous government largess, right? If all of those government subsidies went away, you'd have a city of maybe 50,000 tops, that kind of thing.

Chalfin: But it wasn't always a subsidized city, right?

O'Donnell: No, you're right. That was really since World War II. But what Colorado Springs has had, and this is why it can be easy to villainize Colorado Springs, is Colorado Springs has always had a culture of where they don't want to pay their way. So Colorado Springs has been typically kind of Libertarian, anti-tax, very and generally run by developers.

Chalfin: I mean, that's a stereotype, though.

O'Donnell: I think stereotypes can have a lot of truth in them. And so yeah, I'm generalizing, right? I want to be clear about that. But again, in general, this is how Colorado Springs has done things. So you grow, grow and become wealthy, but in the context of that growth, you create problems. And the Fountain is a great example of that, but there's others.

But then, Colorado Springs has been very reticent to deal with the problems it creates. So you kind of go back to this kind of question of capitalism, really. You privatize the income and the benefits and you socialize the effluent, so to speak, right?

So when we come back to the circle, back to the Fountain, Colorado Springs has been allowed to develop over the past 80 years at an enormous rate. And that development has caused all kinds of problems. But the residents of Colorado Springs and the developers driving that sprawl have never wanted to pay their fair share in terms of stormwater regulations or stormwater taxes or proper infrastructure in a lot of places. And so then they've created this big problem downstream that then has to be dealt with by the taxpayers. Right there you are socializing the externalities. These are called externalities. Pollution is an externality.

So it is easy to villainize Colorado Springs, and I think Colorado Springs should be villainized to a certain extent.

Chalfin: What do you want people to take away from the book?

I want people to, on the one hand, kind of understand the complexity of how we manage our water systems and just how much we've changed our water systems throughout the West. I think a lot of people just don't know. My impression is that most people kind of tend to think, well, this is just how things are, and they've always been this way, but it takes enormous resources to do these major alterations, and they come with big consequences.

The second value I wanted out of this book was as a historical document, as a resource for people in the future to understand what life was like in this watershed at this moment.

I think the most important thing I want folks to take out of this book is to start rethinking your relationship with rivers and how we view rivers, and to start to view them as less of a resource and more of a partner, less of something to be exploited and something to be worked with and worked in conjunction with.

And I think the way we achieve that is by approaching the river again, as a being, as an entity, as a power and a force in and of itself. And to start looking at the river as if it is alive, because it is. Then we may treat it differently, and I hope that we would.