A decade ago, Paonia author Paolo Bacigalupi applied a science fiction lens to the Colorado River crisis.

“The Water Knife” portrays an American Southwest where paramilitary battles break out over a river that is a fraction of its former self. The fortunate characters live in self-contained towers that insulate them from extreme heat and drought.

“It's the one (novel) that people keep coming back to as something they recognize– as being related to their world,” Bacigalupi said.

Observers of the West have called the book prescient for the future it imagined, but in a conversation with Colorado Matters Senior Host Ryan Warner on the novel’s 10th anniversary, Bacigalupi said he undersold the incompetence of political leaders.

“It is far worse and far more stupid than I could have ever imagined,” Bacigalupi said.

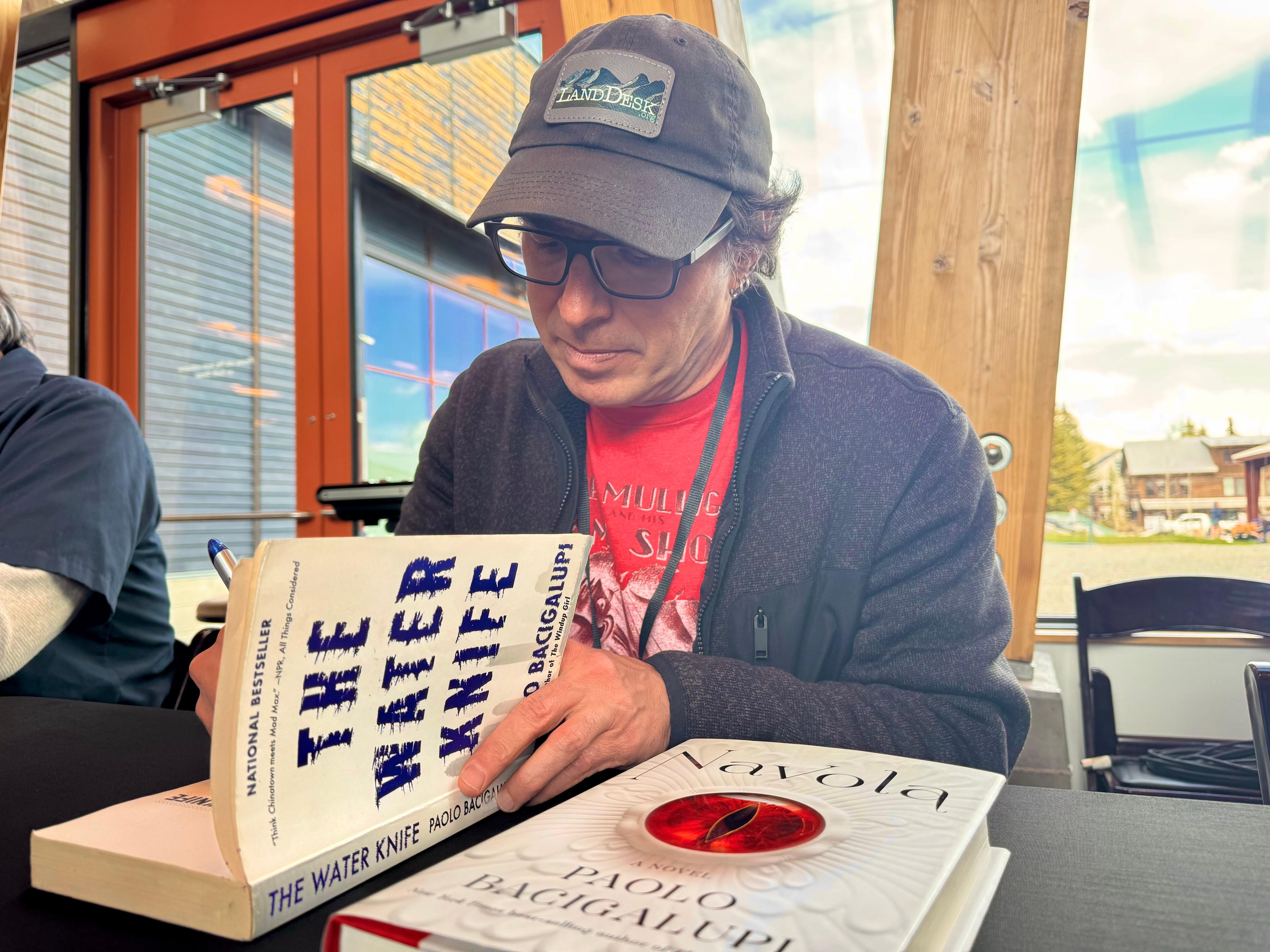

Bacigalupi, who has since ditched climate doom for fantasy with his latest release, “Navola,” discussed “The Water Knife” at this year’s Mountain Words Festival in Crested Butte.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Warner (in a sarcastic tone): “The Water Knife” is about a dying Colorado River and its effect on the American West. A major plot point is set not far from here, at Blue Mesa Reservoir. It has been a decade. Aren't you glad that in that time states have formulated a harmonious conservation plan that averts the dystopian future you imagined?

Bacigalupi: It's so nice to see people look towards the future and say, “let's get together, work together, plan, think, organize, and come to harmonious and successful outcomes. It's really nice. Data-driven, science-driven, reality-driven... Yeah, it's really inspiring to see that happening!”

Warner: Inter-state harmony, just remarkable. Tongue planted firmly in the cheek, but seriously, “The Water Knife came out May 26, 2015.” How does that sit for you?

Bacigalupi: It's interesting because when that book was coming out, Rick Perry was governor of Texas. At the time, back around 2011, there was a huge drought in Texas. All the cities were incredibly dry, the farms were drying up, they were having to put down cattle because the land couldn't support them, they were having rolling brownouts because their hydroelectric dams didn't have enough water in them to drive the turbines. It was a record number of 100-degree days. I remember being down in Texas and thinking, “Oh, you know what? This isn't a drought. This is time traveling.” If we look at climate change and we look at the climate data and we see what the general predictions are, this is what the future for Texas is.

It struck me that Rick Perry was going around and telling everybody to pray for rain. There's a moment where you're like, “Oh, okay, we know what the future is aiming towards, and we see this sort of magical thinking is in power. What kind of world does that build?”

And what I wrote with “The Water Knife,” basically, was, it's the dumb future. When it came out in 2015 though, the United States had just gotten into the Paris Climate Accords, Obama was still president, we were taking some active steps to engage with climate change, and in fact, I think we even had a rainy year that year, as well. So, there were some things that kind of made you think, “Ah, maybe this book is actually irrelevant. I'm not actually talking about any relevant future. I just had a moment, I saw some trends, but maybe they weren't the dominant trends.” So, yeah, you fast-forward to now…

(Photo: CPR / Michael Hughes)

Warner: Just wait a little.

Bacigalupi: Yeah. And it is far worse and far more stupid than I could have ever imagined. And the book feels more relevant than it did when I wrote it. It's disturbing and depressing at the same time.

Warner: The former water manager for Las Vegas, Patricia Mulroy, was an inspiration for The Water Knife, she was once called “The Empress of Vegas Water.” Did you ever find out if she read the book?

Bacigalupi: I don't know if she read the book, but I know she heard about it. We were both at a water conference and she came up to me and she said, "I have a bone to pick with you."

Apparently, lots of people in the water management community had read the book, and they all were like, “We see where you [Mulroy] were written into the book.” I have a version of her as Catherine Case, and she's sort of Pat Mulroy 4.0 or something, if she had helicopter gunships and an even bigger budget, and she could blow up some dams and some water treatment plants to make sure that the water kept flowing to Vegas. So, apparently she'd gotten some ribbing about the book, and so she wasn't super pleased with me, actually. It was kind of funny because, and I told her at the time, “Honestly, I wrote it as an homage to you because you are one of the few people who seems to be genuinely engaged with the realities of the Colorado River and its scarcity.”

Not only in the ways that she pushed the Southern Nevada Water Authority to manage water in much, much more effective ways, and to build it in the first place, but also that she has never been someone who stands around saying, “Oh yeah, it's just going to be fine,” and tries to whistle past the realities of just how difficult it is. And so, it was kind of interesting to see her response because honestly, I was always pretty impressed with just how no-nonsense she was, and how effective she was at protecting a city that has some terrible, terrible water rights.

Warner: If you were going to write “The Water Knife” today, is there much you'd change? Would you make it dumber?

Bacigalupi: Well, there isn't a lot. I think I hit pretty much every single note. It's a story about Vegas planning and Phoenix failing to plan. It's a story about the states not cooperating. It's a story about the federal government becoming increasingly anemic and incompetent, and the states moving into that power vacuum. It's a story of people who win, but in really selfish ways. And it's a story of the climate losers who are many. And I think I hit most of those notes pretty well.

And I've been thinking about what the next science fiction book that you would want to write is, or what you would want to illustrate. A lot of times people have described “The Water Knife” as dystopian, but it's not a dystopian book, it's just an extrapolation, it's just science fiction. If you were going to write a dystopian book, it would describe the absurdity, and I think it would be satire of some kind, trying to get at the absurdity of our continuing belief that we can keep doing the same things and it'll just work out.

It's really hard to write incompetence believably, and it's sort of-

Warner: Let's pause there! It's really hard to write incompetence believably?

Bacigalupi: Yeah.

Warner: Because you don't trust it?

Bacigalupi: Well, it seems too simple. It seems too pat. Even certain versions of evil become too pat. It's like, “Oh, why did they blow that up? Or why did they mess that up? Or why did they tear apart that agency? Spite, apparently.”

And this is where you get to the idea of the Mad King, where it's like, “Oh, we're being managed by caprice. There's no longer an idea of management even.” I think you can write that story now. I think that when I was writing “The Water Knife” before, the idea that people would be operating simply by caprice, that extrapolation would have seemed a little too far-fetched.

Warner: Wow.

Bacigalupi: That would have been the impossible sell, looking back.

(Photo: CPR / Michael Hughes)

"The Water Knife" by Paolo Bacigalupi

Warner: Is “The Water Knife” the book you are asked about most?

Bacigalupi: It's the one that people keep coming back to – as something they recognize as being related to their world. More than “Ship Breaker,” more than “Windup Girl,” more than other science fiction books that I've done. “Water Knife” is the one where I continue to have people mention, "Oh, I saw this news story about the Colorado River." Or, "Oh, I saw this news story about water in some neighborhood in Phoenix." Or, "Oh, I saw this news story about climate refugees." Or, "I saw this story about forest fires, I saw this story about fires in urban areas…" Again and again and again. It's the one where the thing that they thought was an extrapolated object suddenly feels like their present-day object. That's normally when somebody will email me or reach out or ask to interview or whatever.

Warner: Well, congratulations on the 10-year mark, and, Paolo, thanks for talking to us.

Bacigalupi: Thank you.