The invasive zebra mussel species is spreading across Colorado and could eventually impact drinking water, agriculture and ecosystems if they aren’t eradicated — something experts say is really hard to do.

Colorado Parks and Wildlife announced July 3 that several new colonies of the species were discovered this summer in Eagle County and the Colorado River near New Castle and Highline Lake State Park. The additional detections mean the river is now considered "positive” for the species from the confluence of the Roaring Fork River north of Aspen to the Colorado-Utah border.

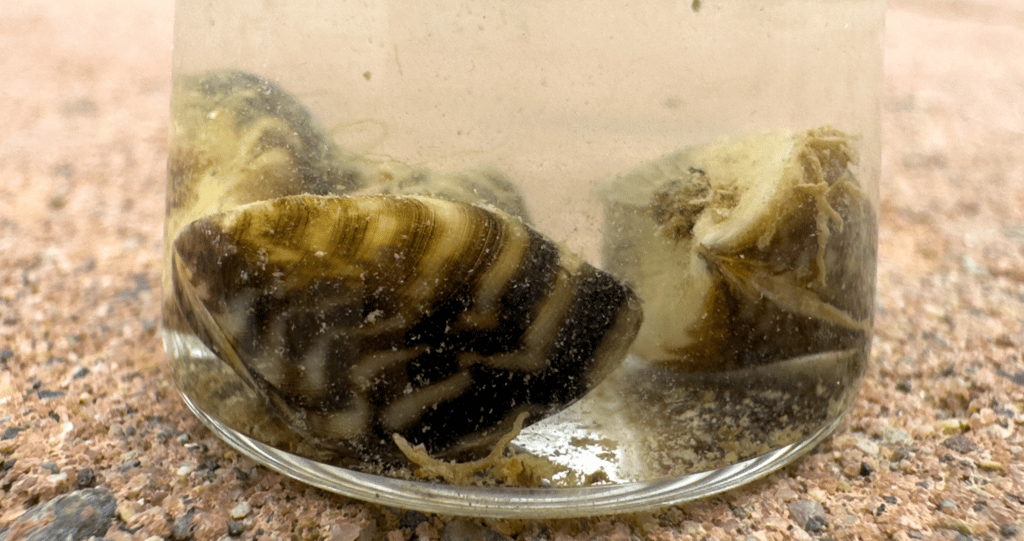

While they may be small — no bigger than your thumbnail when fully grown — these little critters can cause a lot of damage.

Zebra mussels are native to eastern Europe and first arrived in the Great Lakes region in the late 1980s. They have since spread to more than 15 states across the nation. In regions where they are most prolific, they’ve clogged municipal and industrial water intake systems, costing cities millions in mitigation efforts because they’re so difficult to get rid of.

“Eradication is a very lofty goal and has honestly rarely been achieved,” Colorado Parks and Wildlife invasive species program manager Robert Walters said. Major U.S. cities using reservoirs with zebra mussel infestations for drinking water, like Austin, Chicago, St. Louis and Detroit, have all had to create special mitigation systems to prevent them from clogging water intakes. This can look like screens, chemical treatments and mechanical removal, all of which add to operational costs that are sometimes passed on to consumers.

In Texas, zebra mussels were detected in Lake Travis, just outside of Austin, in 2017. About a year later, residents struggled with “smelly tap water” due to zebra mussels in the city water system, according to KUT News, Austin’s NPR affiliate. Austin Water was forced to flush lines in order to improve odor and taste. In 2020, the city council approved $4 million to continue combating the infestation.

Right now, more than 40 million people across seven U.S. states rely on the Colorado River Basin for drinking water. Should the mussels continue to spread, other major cities like Las Vegas, Phoenix, and Los Angeles could eventually be affected.

Fifty percent of Denver’s water comes from the Colorado River Basin. However, so far zebra mussels have only been detected below Glenwood Springs to the Colorado-Utah border, a section of the river used mainly by communities on Colorado’s western slope like Grand Junction, Fruita, Palisade and part of the Grand Valley Domestic Water Users Association.

That’s where Walters said other local sectors could also eventually be impacted by the infestation.

“If the mussels start to clog up water distribution systems that are used to deliver water, let's say to the peaches out there in the Palisade area, then either they won't get water or those irrigation water users will have to do significant maintenance to ensure they can continue to deliver water to the agricultural goods,” said Walters.

The species also has the potential to change a river’s ecosystem.

“A single mussel can filter a liter of water a day and they are often filtering out the phytoplankton, which is, in many cases, the basis of the aquatic food web and ultimately can have significant impacts on any fish species that's sharing water with the mussel,” said Walters. “These might be some of the sport fish species that people are familiar with, such as our Rainbow Trout.”

And while the mussels might make waters look clearer by eating much of the natural plankton and some algae, they do not filter out blue-green algae. According to the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, that increases the chances of toxic blue-green algae blooms. Additionally, zebra mussels will often smother native mollusks, killing them and further affecting the water's natural filtration systems. Meanwhile, fish that eat native mollusks could be threatened by a diminishing food supply, or fish that switch over to eating zebra mussels have been found to weigh less because zebras mussels provide fewer calories than native mussels, according to Wisconsin Public Radio.

Zebra mussels are similar to another invasive mollusk, the quagga mussel, which has not been detected in Colorado’s lakes and streams. However, they are routinely intercepted on watercraft through the state’s watercraft inspection and decontamination program.

“They are well established in waters outside of the state, including several of the Lower Colorado River impoundments such as Lake Powell and Lake Mead,” Walters said. “(Zebras and quaggas) are known to have very similar impacts.”

Like zebras, quaggas also eat phytoplankton and harm the food web. However, zebras require hard surfaces to survive, while quagga mussels can spread on soft lake beds, according to WPR.

Why are zebra mussels so hard to get rid of?

Zebra mussels are prolific breeders. When in their larval stage, the free-swimming organisms can’t be seen by the human eye, making them really hard to detect.

“Under the right conditions, [zebra mussels] can spawn year round with numbers going as high as a million offspring from a single female. They also have what’s called a byssal thread, like a root or an anchor that they use to both chemically and mechanically bond themselves to surfaces.” Imagine small hair-like structures that grip onto hard surfaces like rocks, boats and even other aquatic species with hard shells. “It might feel like a sandpapery texture on the surface. At that point, we refer to them as settlers. They can still be pretty difficult to identify at this stage, and then eventually those settlers grow up or mature into an adult form.”

Colorado has been working to eradicate adult zebra mussels from Highline Lake since the fall of 2022.

“In the first year, Colorado Parks and Wildlife reduced the lake's water level to approximately 20 percent of its total volume,” Walters said. “That was to expose the vast majority of the zebra mussels that may have been present to freezing and drying conditions, which is not a suitable habitat for the species.”

In the remaining amount of water, the state applied an EPA-approved copper-based molluscicide like the one used in Austin’s Lake Travis which aimed to kill off the remaining species. “Unfortunately, in the fall of 2023, we discovered additional zebra mussels out there in Highline Lake. Following that discovery, we implemented another treatment, and then in the winter of 2024 into 2025, Highline Lake was completely drained,” Walters said.

Now, the lake is open to recreation, but all boats that enter must go through a cleaning process as they exit.

Stopping the spread

Walters recommends all gear get cleaned after each use because even a tablespoon of water that gets left in a gear bag can carry microscopic invaders that could be transferred the next time you use your equipment.

“As long as everybody is cleaning, draining, and drying all their equipment every time they go out, then we will significantly decrease the possibility of these things moving from location to location,” Walters said.

A new map released this summer shows where you can find gear and watercraft cleaning stations across the state.

In January this year, Congress merged several recreation and conservation bills to improve access to public lands, modernize infrastructure and tackle invasive species, among other goals. The bipartisan EXPLORE Act set aside $900 million for such projects, but Colorado Parks and Wildlife told CPR News it’s still working to understand how the law’s authorized grant programs might be accessed for zebra mussel mitigation efforts in our state. In the meantime, Colorado Parks and Wildlife will continue regular testing across the state in an effort to mitigate as early as possible and hopefully achieve eradication. “Every new detection puts us one step closer to achieving this desired outcome,” Walters said.

Meanwhile a third invasive threat, the golden mussel, was detected in California last October and given a temporary nuisance designation by CPW.

“This is another species with similar but possibly more devastating impacts than zebra and quagga,” Walters said.