A destructive predator has invaded Colorado, and a volunteer army is trying to defeat it.

With fishing poles.

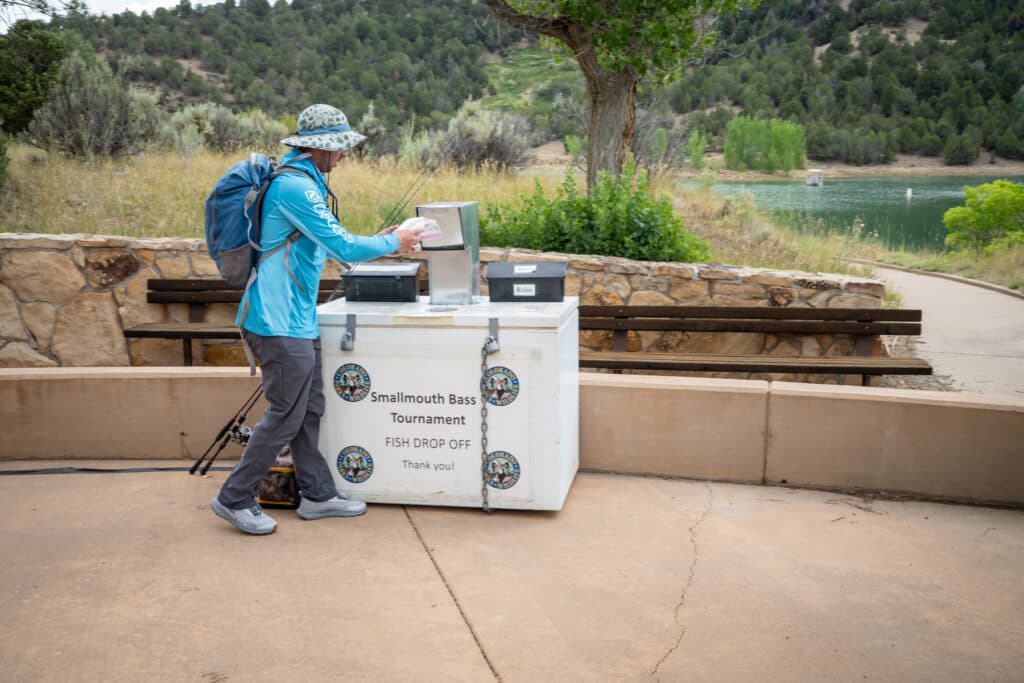

At the Ridgway Reservoir Smallmouth Bass Classic, Western Slope anglers are competing to catch the most invasive smallmouth bass to win a hefty prize and help save native species.

Dozens of fishermen and fisherwomen usually compete, removing thousands of harmful fish from the reservoir just north of the small mountain town of Ridgway. But one competitor tends to blow everyone else out of the water: Chase Nicholson.

The South African-born angler has won four times — every time he’s entered. He chalks up his success to all the hours he’s logged fishing.

On a recent morning, he drifted in his kayak on emerald-green water that was strikingly clear. It was a serene scene. But for Nicholson, it’s also an endurance event.

“It can get ugly out here when the wind's blowing and the waves are 3 feet tall, swells rolling past and you're trying to paddle from one side of the reservoir to the other,” he said.

Nicholson estimated that he paddles somewhere between 6 to 8 miles a day, battling sore muscles and hot weather.

But on this day, the bright blue sky above him made it easy to see the sharp peaks of the Sneffles range in the distance. All alone on a quiet section of the 5-mile-long reservoir near a remote highway, without skipping a beat, he quickly flicked his fly fishing rod back and smoothly cast his lure far in front of him, over and over again.

This is his life for five weeks during the tournament.

It’s relentless but also worth it, he said, to try to nab this year’s $10,000 top prize — all while cutting back the population of an invasive species, “before it becomes unstoppable.”

The tournament takes place every other year, and Nicholson has won it more than anyone else. That success also once earned him a job at Colorado Parks and Wildlife, which hosts the competition. He was hired as an aquatic biology technician.

A fickle foe

Eric Gardunio, an aquatic biologist with CPW, saw Nicholson’s impressive tally a few years ago. So he hired him to fish for smallmouth outside of the tournaments. When he later learned that Nicholson was an ichthyologist and zoologist, he hired him on a more permanent basis.

Both men know how vital it is to keep smallmouth from taking over. Female smallmouth bass can produce around 30,000 eggs. They have few predators. They’re also cannibals. These camo-colored fish with distinctive tiger stripes can gobble up other fish up to about 8 inches long, around a third their own size.

“They just open that mouth up, suck the fish in and swallow it whole,” Gardunio said.

Their diet includes beloved native and endangered species, like the humpback chub and razorback sucker. Smallmouth have already invaded the Green and Yampa rivers, but not the Gunnison and the Colorado rivers, where this reservoir eventually flows.

“We’re just trying to reduce the chance of those fish getting out into those waters downstream,” Gardunio said.

Wildlife officials also work to estimate how many smallmouth bass are in the reservoir and track how the population changes.

Gardunio fired up a generator that powers two bobbing metal buoys in the front of a CPW boat. As the metal orbs dragged through the water, they sent out an electrical pulse that stunned nearby fish.

Lanie Smith, a fisheries technician with CPW, scooped up their temporarily limp bodies and dropped them into a bucket. Later, they tagged those fish, which helped inform the state’s estimate of how many there are in the whole reservoir. Then they re-release the fish for the tournament. Some of them will be worth a surprise $1,000.

Stopping the spread of invasive fish is “a measure of how we're doing as a species,” Gardunio said.

The invasive bass are here because people introduced them, likely due to their popularity for fishing in places like the Great Lakes, where smallmouth are native.

Gardunio said since humans brought them here, it’s our job to remove them.

Certain humans, like Nicholson, are particularly good at doing that. As he reeled in a thrashing smallmouth, he said he still feels a rush of excitement with each fish he catches, even if it’s his 100th of the day.

“My whole life, fishing has been my hobby, my passion, my interest. It's been everything,” he said.

That started during his childhood in South Africa, when his opa — his uncle — taught him the sport. These days, Nicholson is grateful the ranch where he works now gives him this time off.

He called it a “recharge.”

“It puts me back into my happy spot,” he said. “I've got my kind of fishing fix, and one month of fishing does that for me for a year.”

It could also net him a nice paycheck.

The tournament began July 5 and runs through August 10.