The San Luis Peoples Market had an ambitious goal: turn a weathered old grocery store that’s been passed down from generation to generation into a vibrant food co-op.

When you walk into the store, you are faced with both worlds — a wooden donkey car that dates back to 1951 and a brand new deli counter, an 1800s adobe facade and new wooden paneling.

But it turns out, refashioning a century-old business isn’t easy.

“Every week we found unexpected challenges,” Devon Peña, executive director of the Acequia Institute, the nonprofit behind the market, said.

That deli counter arrived broken.

“Every single glass part of it was smashed, destroyed,” Peña said.

And the donkey cart meant to feature produce from San Luis Valley farmers was full of potatoes from Idaho during a visit in late June.

Peña had envisioned tiny San Luis rallying around a transformative vision of a food co-op and education hub. Residents would learn to grow their heirloom crops on small plots. They would sell that produce alongside their neighbors and then attend cooking classes steeped in nutritional efficacy and indigenous tradition.

But the market is stumbling out of the gate.

Initially expected to open in the fall of 2024. It didn’t open until May of 2025. It’s been marred by the continual nightmare of renovating a 168-year-old adobe structure, by the logistical challenges of delivering specialized equipment to an isolated region, by running a business in an underserved part of the state, and by a harassment lawsuit against Peña himself.

The building itself was infested with asbestos, lead paint, and mold. It required complete rewiring to be compliant with fire codes. Its low-lying position has water seeping up through cracks in the foundation as the team makes preparations to lower the surrounding water table. Walls buckle. The floors warp.

Remediation work began two years ago. Much of it has been completed. Decades-old wood paneling has been restored. Rolling shelves of food can be wheeled into various arrangements on the blue-green polished concrete floor. Though, delays have hounded each step of the restoration as contractors struggled to staff the far-flung project.

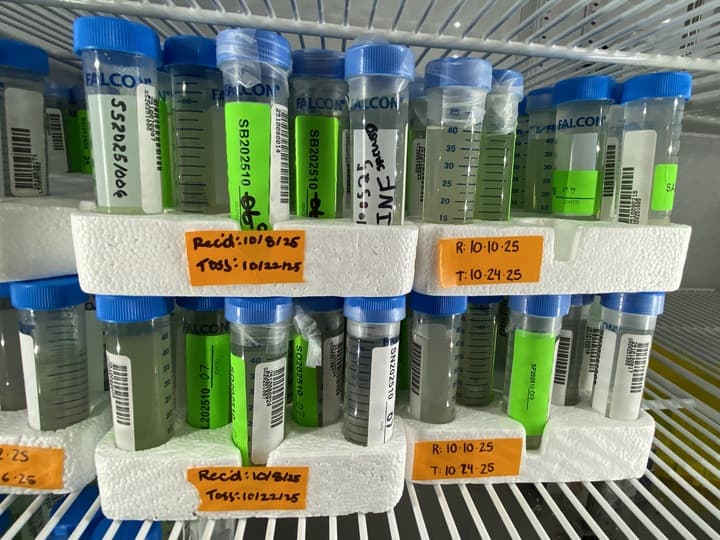

Beyond the building, equipment — like the deli counter — has arrived damaged. A new freezer won’t reach the freezing point. Replacements are expected to take weeks or months to arrive. Until they do, a core piece of the market’s business plan remains unrealized.

Staff also contend with the sometimes competing interests of its mission to provide fresh and local products and the community’s desire for highly processed, easy-to-prepare options like frozen pizzas and hash browns.

“Changing how people eat is the hardest thing to do,” Peña said. “We have to remain open to stocking in our inventory items that we'd rather not sell, but we stock it anyway because of local preferences.”

Acequia Institute interns, usually high school students, work through the summer growing vegetables on Peña’s small nearby farm. They consult with professional chefs to provide free cooking classes for the community. The classes are well-attended, but residents’ ability to buy the ingredients has been hampered as well. The market applied for SNAP and WIC authorization in May. As of the beginning of August, their status was still under review. That’s prevented many customers in the rural, impoverished region from shopping at the store.

With these troubles, sales at the market have not met projections.

The initial payroll of 13 employees has dropped to six core team members. Meanwhile, some of the Acequia Institute’s resources are now going toward legal expenses.

Addelina Lucero — a Native American woman hired in 2021 for a two-year, grant-funded position as a Community Outreach and Education Coordinator — has filed a lawsuit against Peña and the Acequia Institute for wrongful termination as well as racial and gender discrimination and harassment. She argues Peña fired her in July 2022 in retaliation for her reporting what she describes as his hostile work behavior to the institute’s board of directors.

Peña rejected the lawsuit as “completely baseless” but had no further comment. Lucero’s representation also did not provide comment.

The market had hoped to hold a grand reopening for the community’s Fiesta de Santiago y Santa Ana festival the last weekend of July. Like with many elements of the San Luis Peoples Market’s vision, it has been delayed — this time until October.

But signs could be pointing toward better days. On our most recent visit, in August, the donkey cart had just sold out of at least a bushel of sweet peas grown locally in the San Luis Valley.

As intended.