Davarie Armstrong was a rising star in Denver South High School football with a bright future ahead of him.

At the age of 17, several colleges had sent scouts to follow his progress, then his life was tragically cut short.

In July 2020, while at a party, he was killed by teenagers, including a 15-year-old. One was armed with a semi-automatic rifle.

As dreadful and devastating as it was, Armstrong’s shooting death was not a one-off incident; it’s part of a trend.

Teen homicides are steadily rising in Colorado.

Photo: Davarie Armstrong's family and friends fill South High School's football field to mourn his sudden death. July 14, 2020.

Since 2020, guns have been the leading cause of death for U.S. children and adolescents, surpassing motor vehicle accidents, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Teen homicide cases are rising, and Black teens are disproportionately represented in these numbers.

In Colorado, the 18th Judicial District reported that first-degree murder cases in the juvenile court have nearly doubled from 2022 to 2024.

Why is this happening, and what can we do to save Black teen lives?

I’ve spent 18 months recording the experiences of young Black men, community leaders and mothers impacted by guns.

And I found the issue is more complicated than stopping kids from obtaining guns.

The problem is deeper than that.

Why we produced a podcast about youth gun crime

This is an immersive audio documentary.

“Systemic” aims to provide a deep, thoughtful look into what pushes some teenagers into a life of gangs and gun violence.

The podcast also highlights people trying to find solutions.

This podcast is not a conversation on gun reform; it seeks to answer one question: Why are teen homicide rates rising?

To answer that question, I interviewed mothers impacted by guns, a young person who was part of the Crips gang, and police and community leaders.

Each story shows a part of a solution and like a jigsaw puzzle, we assemble the pieces to see the big picture, and the barriers that prevent change.

This podcast focuses on the unique solutions put forward by the Aurora Police Department, youth and community leaders and legislators.

We hope you come away from “Systemic” with a better sense of the people working to reduce youth homicides, and solutions that can be supported or replicated in Colorado and beyond.

Impact of teen-on-teen gun violence

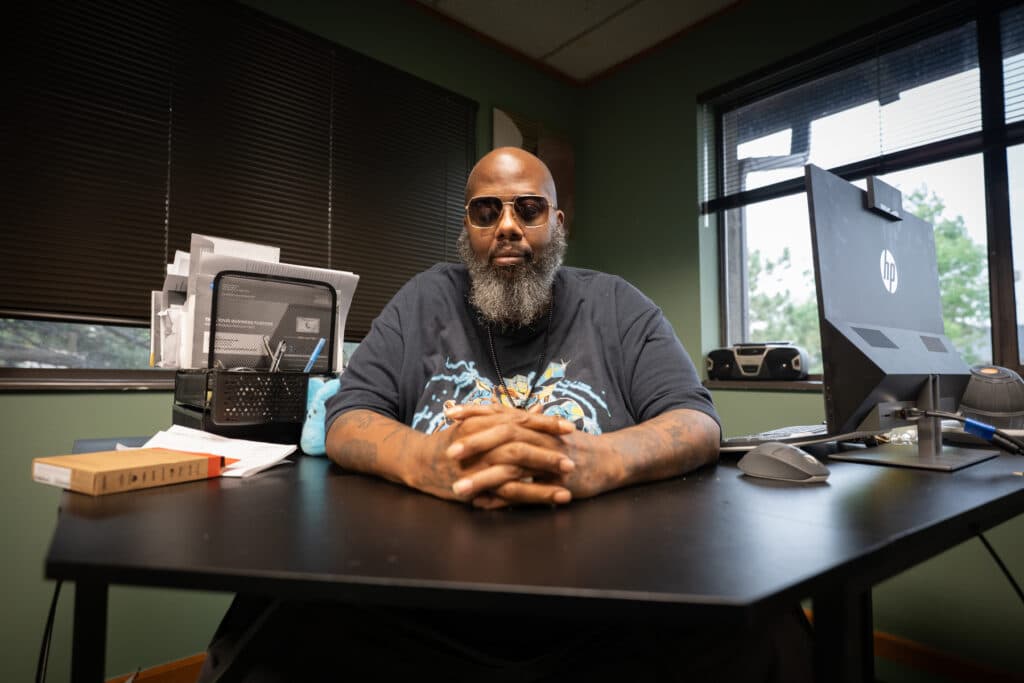

Jason McBride is a youth and community leader who has worked with the courts to help young people at risk of incarceration fulfill a plan of action designed to stop them from reoffending.

In McBride’s line of work, he pretty much expects bad news every day. As a youth violence intervention specialist, he works with young people who have a history of firearm offenses or have been initiated into gangs and gun culture, and tries to give them a future away from a life of crime.

This work is not easy. He remembers the night Davarie Armstong was killed. At 3 a.m., a friend called to say there was a shooting and one of the people who shot Armstrong was young. Very young.

“I hate talking about this. This is the worst.”

One of the shooters was 15 years old.

McBride described him as “A young man who was probably the same size as the AK-47 that shot him.”

Police didn’t recover the guns, but they did recover the bullets that show the gun that killed Davarie was either a semi-automatic rifle.

This tragic event has haunted McBride, but it also drives him to do everything he can to stop young people from killing each other.

One young person he managed to steer away from crime is Sam Elfay.

Episode 1: Educate

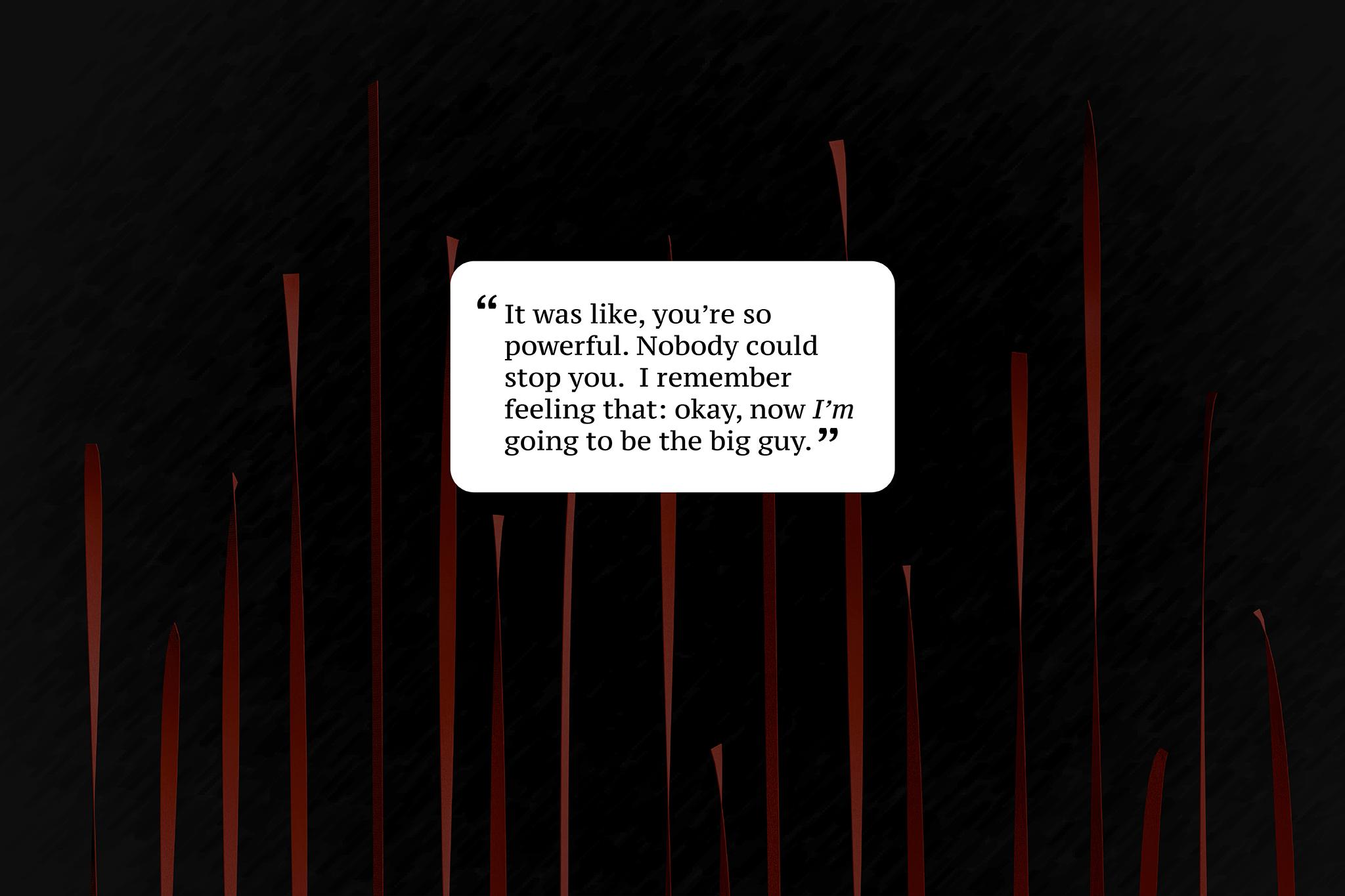

When Sam Elfay was just 13 years old, he was struggling to stay in school.

His flirtations with petty crime began as something to do as he lost interest in class. Basketball was the only thing that held his interest. It’s not that Elfay, who’s now 24 years old, didn’t have a curious mind; it's just that he found lessons dull. He used his curiosity for other things.

“I figured out a way to block my dad's phone number from the school system using their phone. So I wasn't in school much,” Elfay said.

As soon as his father would drop him off at North Middle School in Aurora, he’d wait until his dad left, then skip class. Elfay’s appetite for more danger in his life grew. He started to break into houses and cars, stealing whatever he could get his hands on. Then one day he stole a gun from someone’s car.

Elfay remembers the moment he first held a firearm.

Stealing a gun changed everything.

He started taking more risks. He would rob people on the street at gunpoint.

By the age of 15, his ambition to get more guns forced his father to make a difficult decision.

“My dad had actually found a submachine gun; he had found it between my mattresses,” Elfay said. “He kicked me out of the house and told me to go live with my family in Seattle, or to go live on the streets.”

So Efray went to live with his aunt in Seattle, but things didn’t improve. He fell into the Crips gang.

“We got 20, 30 other brothers of us doing the same thing. We can go smoke link, [pot] do what we need to do.”

So how do you reach a young person heavily involved in the Crips gang and gun crime and persuade him to go to school?

Educators and community leaders say it’s difficult, and sometimes impossible, to get kids to turn their lives around.

How do you motivate young people who have missed parts of a school year, or entire years of school, to return? And how do you keep young people from returning to gang life when school life gets tough?

It takes a special person to make that type of breakthrough. Jason McBride is the one person I’ve met who does not seem to have that problem.

Elfay returned to his dad’s home in Aurora after completing his sentence at King County juvenile detention center in Seattle. McBride was there to meet him and support him as he tried to turn his life around.

McBride instantly struck a good rapport with Elfay. They shared a common bond; McBride is a former gang member himself. When McBride was 18, he got shot, and it was a reality check for him.

He could see where his life was heading and he didn’t want that lifestyle anymore. He went to college and has spent the next 33 years trying to get Black teenagers to see a future beyond gangs.

McBride said, “There's a Chinese proverb that is probably my favorite proverb, and it states: ‘If you want to know what's on the road ahead, ask a man that's walking back.’ And that is, I feel like I'm that man that's walking back, and I'm walking back from a lot of these ugly things that these kids are trying to walk towards, and they don't know what's up there.

“It's loss, it's separation, it's incarceration, it's drug abuse, it's all these ugly, ugly things. And I'm coming back from those things and these kids are walking up there and I'm trying to stop 'em in that road and saying, ‘Hey, let's find you another path because you don't want to go up there.’”

With the help and support of McBride, Elfay graduated from Aim Global Academy.

But education is just one of the solutions McBride is pursuing.

Episode 2: Bridge

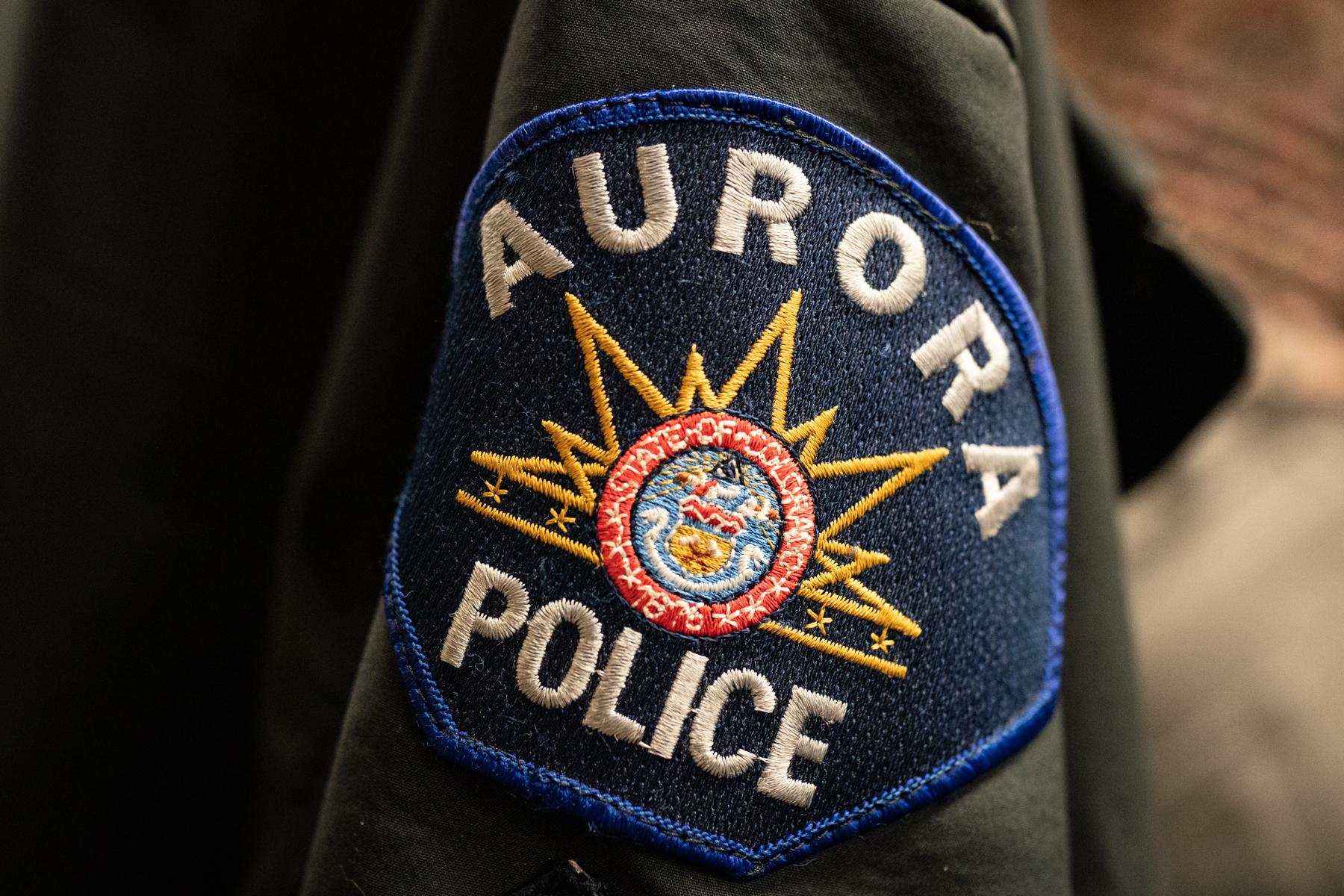

Lisa Battan is the Intervention Programs Manager of the Aurora police unit called SAVE, Standing Against Violence Every Day.

She is keen to make changes to the way young people at risk of incarceration get policed. She believes the old way of arresting and incarcerating teens wasn’t changing anything.

It didn’t stop youths from joining gangs, nor stop innocent young people from being killed. Something needs to change, she said.

The Aurora Police Department learned about the concepts behind SAVE, a policing model that brings together community and law enforcement as they tackle violent street groups.

It’s modeled on the Group Violence Intervention (GVI) strategy used by Oakland, Chicago, Detroit, and New Orleans police departments. They each collaborated with community leaders to reduce gun crimes, with the intention of keeping individuals alive, safe and free.

The city of Aurora has been using this method of policing for 24 months.

Anna Bungartz is a lieutenant with the Aurora SAVE program; she is one of a team that selects suitable candidates for the program, who have a history of gun crime, robbery, shooting, firearms and weapon possession, but also have expressed a desire to change.

The SAVE team visits the candidates at their homes with a community leader present to explain the deal.

The SAVE team brings a plan for how to move ahead, sometimes advocating for relocation to another family member’s house, helping them get back to school, or learning a trade — whatever seems like the best path to stop them from reoffending.

If the young person commits another crime while on the SAVE program, they risk having the courts issue the maximum sentence for the crime.

McBride is a huge fan of the program and has worked with the SAVE team as a community leader.

But he also recognizes that people in his community may not support the program.

McBride stands against a tide of Black and brown community anger about policing in Aurora, and the distrust of police goes back decades.

The community is angry that some Black men have been killed in routine police traffic stops.

APD has received a barrage of criticism for its policing of the Black community, including its role in the deaths of two unarmed Black men, Kilyn Lewis and Elijah McClain.

McBride is angry at Lewis’ fatal shooting by police and the death of Elijah McClain after he was aggressively stopped by police.

But he also wants the community to see what he sees: that this program is saving Black teens from a life of gun crime.

Episode 3: Legislate

Davarie Armstrong was killed on July 12, 2020. His mother, Angel Shabazz, had no idea that Davarie was going to a party in Montbello that night.

Just days before, she'd overheard Davarie and his stepdad secretly plotting to get her a birthday present, so when he was late coming home, she thought he was out shopping. But at 10 p.m., she called him.

After learning that he was at a party, she told him to come home immediately. That was the last time she heard her son’s voice.

At the party, Davarie tried to break up a couple who were fighting.

Other young people at the party did not like Davarie separating the warring couple.

And they shot him.

Shabazz said her son was shot seven times.

The guns were never recovered, but the bullets from the scene indicated that it was this type of high-powered rifle.

How did teenagers obtain a semi-automatic rifle?

That’s the question Shabazz still wants an answer to. She also wants to know if other teens can be prevented from getting guns like this in the future, and she thought Colorado’s legislature may have solutions.

She is angry at the parents. She feels that the parents of the kids didn’t take responsibility for their children's actions.

“I have never got an apology from none of the families. I've never been reached out [to],” she said. “They might've lost their child for 10 years [in prison], but mine's just gone forever. They'll still be able to talk to their family, they'll still be able to see them, put money on their books, know that they're eating three meals a day. I'll never get that opportunity.”

Photo: Davarie Armstrong's mother Angel Shabazz.

Democratic lawmakers at the statehouse passed a number of new gun laws this year.

Senate Bill 3 requires anyone in Colorado after Aug. 1, 2026, to have a permit and complete 20 hours of firearm safety training in order to purchase high-powered firearms with detachable magazines.

The new law will also prohibit anyone from buying accessories for semiautomatic guns, like binary triggers and bump stocks.

When Shabazz found out legislators were changing laws for semi-automatic rifles, she was hopeful. But now, she is not convinced that this legislation would have saved her son, because it does not address the issue of stealing guns or buying guns illegally online.

Colorado state legislators attempted to pass a bill prohibiting the sale of guns on social media platforms, which McBride advocated for in Denver.

Despite their efforts, Governor Jared Polis vetoed the bill.

He had concerns about privacy and the First Amendment.

Today, McBride and families continue the fight for more gun reform. Shabazz has created the DJ Armstrong Foundation to honor her son’s life.

This foundation was set up to give young people resources to help them gain academic and business success.

Shabazz said, “Davarie didn't get to accept his diploma. I had to accept his diploma when I worked so hard to get him to graduate. So not getting to see him go to prom, not getting to see him graduate.”

This pain has driven her to make sure all young people get opportunities to change their lives.

Systemic credits

Story by Jo Erickson

Produced by Shelby Filangi

Edited by Rachel Estabrook

Audio produced by Shane Rumsey and Stephanie Wolf

Graphics by Kevin J. Beaty and Jodi Gersh

Photos by Kevin J. Beaty, Stephanie Wolf and Hart Van Denburg