Drive about three hours west of Denver, and you’ll likely come across two hot springs that are relaxing attractions for both tourists and locals.

Founded in 1888, Glenwood Hot Springs Resort is the older, larger and busier of the two, with a big recreational pool and a handful of spacious soaking pools and a few cold plunges. It’s family-oriented and loud, with lots of kids and sounds. On a sunny summer day, thousands of people might show up, on vacation from nearby states, to splash around.

Founded just 10 years ago and located within a few miles, Iron Mountain Hot Springs is quieter and more subdued, with smaller hot tubs, greater in number, with an adult section, soothing zen-like music, minimalist aesthetic decor, and mainly adults murmuring softly and looking up at the sky while their stress melts away.

Both spots attract guests with the same perk: water - about 3.5 million gallons per day - that naturally bubbles up from the earth and is captured right on site, so guests can relax and luxuriate in what some say is healing water rich in minerals that improve the way one’s body feels.

One of CPR’s listeners wrote in to ask us to find out more about one aspect of a soak that doesn’t meet the eye, that probably isn’t crossing the minds of most guests as they get so hot in a geothermal tub that they decide to take a cold plunge. Specifically, the question was: how does that water that people soak and luxuriate in, whether piping hot or bracingly cold, get filtered?

Always up for a road trip (especially one that promises a relaxing soak in hot spring water), I got clearance from my editor, then invited along my colleague, CPR’s visual journalism editor Hart Van Denburg and we hit the road.

He took the wheel of CPR’s vehicle for a three-hour, one-day trip to visit both hot springs. Our mission: to find out onsite what different steps go into turning slightly green, semi-smelly fresh spring water into smell-free, safe, clean and soakable hot water. The mission required setting up appointments with the water system leaders at both facilities, then going on pre-planned tours of each filtration room – a series of tanks, pipes and vats, and massive amounts of sand of various grades, all of which made perfect sense to two dedicated filtration czars.

Glenwood Hot Springs Resort

First, we met Brian Ammerman, who has for about a decade served as Pool Maintenance Manager at Glenwood Hot Spring Resort, leading a team of a dozen certified pool operators.

“So we have multiple different filtration systems for different pools,” he said, speaking of the resort, which also includes an athletic club, a hotel, places to get food, and seating both in and around the pools.

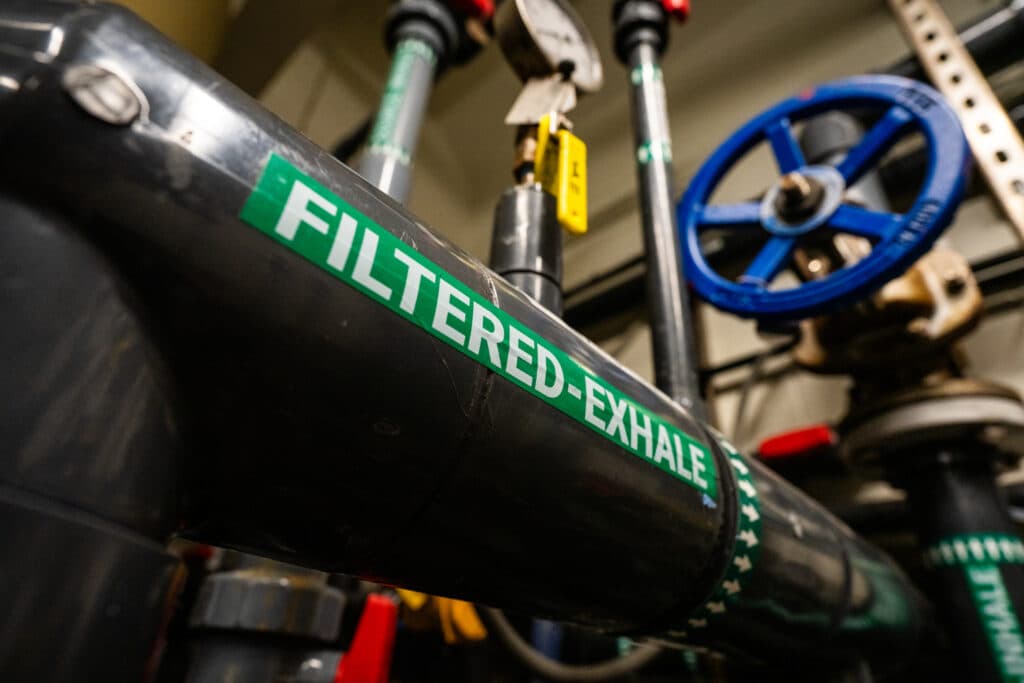

Out of sight of a lot of guests is an open receptacle with natural source spring water that is geothermally heated, bubbles up into the resort, and is routed to different mechanical buildings to filter the water and send it to the pools. Upon arrival from the earth, it’s captured there and then piped into the filtration. For starters, the water’s journey begins with it going through a Leopold gravity filter that traps whatever particles the unfiltered spring water might contain. Simply put: “It’s seven different layers of media, so the water’s pumped up and then it just filters down [by] gravity through seven different layers, then back out to the pool,” Ammerman said.

Those seven layers include four different types of gravel, as well as granule-activated carbon, and anthracite and silica sand. Using a combination of gravity and hydraulics, the filtration system runs 24/7, removing both what people bring in on their bodies, as well as whatever might naturally find its way into the water. “So that could be suntan lotion, makeup, human hair, skin... and any organics: leaves, pine needles … get filtered out as well.”

That’s the filtration system for what they call the legacy pool (a large hot pool where most people sit, some of them on jetted chairs in the water) and the grand pool (for swimming, not quite as hot, but filled with the same spring water).

In 2024, the resort opened five more pools, and for those, the filtration system is a bit different. “These are on high-rate sand filters, which are under pressure,” rather than gravity and hydraulics, completing the filtration of water recycled from the pools and from the spring itself in about the same amount of time as the older system that began in the 50’s, he said.

An additional filtration step to catch anything the first step missed is a state-of-the-art ozone system to oxidize whatever’s left over from the first step. “It helps us maintain a very clear and pure water quality,” he said. Also located in the filtration system room away from guests, it sends the water up and through additional piping before it goes out to the public.

The water starts out slightly green in color, then, once filtered, it’s clear like the color of water in a swimming pool, Ammerman said.

Iron Mountain

A short drive away is Iron Mountain Hot Springs, which opened in 2015 with a very different vibe. It’s quiet and mellow. In the place of sounds of splashing are sounds of calming music and some soft voices.

Among the guests on a recent Friday were two long-time friends who came to spend the day regrouping from the pressures of everyday life, and a couple who’d come to the springs after receiving free admission for a work-related relaxing retreat from an employer as a way to express gratitude.

People tended to find a pool they liked and stay in it long enough to reap the purported health benefits. In the hottest pool, staffers were heard recommending a 15-minute maximum dip so as not to overdo it.

At Iron Mountain, there are 32 pools, 14 of them with a twist: they have replicated the unique mineral formulas mimicking hot springs from around the world, including the Dead Sea and Blue Lagoon. Each pool is a separate circular rock-trimmed structure, more intimate and cozy than its larger but friendly competitor down the road.

Both springs have in common the fact that the free-flowing spring water is hot enough to heat their bathhouse and part of the property's geothermal snowmelt system for pathways, which saves money on fuel costs. “If the water’s coming in at 119 and our battery loop is at 110, it will strip nine degrees off of that mineral water before it goes into the filtration system and then out to the pools,” said Collin Langer, Water Quality and Safety Manager at Iron Mountain.

He said five people report to him, and that, like at Glenwood Springs, a sand filtration system is used – one that’s checked all day long. When asked how often he visits the filtration room, Langer said: “Four or five times a day. Yeah, just to make sure that all the pressures are OK. Make sure that we’re maintaining flow from the wells, and making sure that the temperatures are in a manageable setting.”

Filtration, he said, is all about sand: coarse, medium and fine.

“So what happens is that water comes in with whatever particulates it may have. It sprays on top of the sand, and then the suction pulling from underneath the sand pulls those particulates through and they get trapped in the separate layers of the sand.”

Iron Mountain uses activated filter media (AFM), which is recycled crushed glass from a Swedish company that lasts about twice as long as regular filtered sand, which needs to be replaced every six months. AFM gets replaced annually, he said.

“The way that it’s broken, instead of being just a kind of more rounded sand particle, it’s much more coarse, so it can hold onto things a lot better, and it’s harder for biofilms to actually grow on the surface of those,” Langer said.

Although both resorts use sand for filtration, Iron Mountain does not have the added oxidation system that Glenwood Springs uses. That’s because, according to Langer, the smaller individual size of the pools at the newer resort means that the contents of those pools can get fully recycled within a few hours, omitting the requirement of the additional step at Glenwood Springs, where each pool contains a larger volume of water.

Colorado Wonders

This story is part of our Colorado Wonders series, where we answer your burning questions about Colorado. Curious about something? Go to our Colorado Wonders page to ask your question or view other questions we've answered.