His Cheyenne ancestors were pushed out of Colorado in the 1800s. Now he’s among the leaders of Colorado’s Indigenous land back movement

Listen to an audio version of this story:

Rick Williams doesn’t just want your land acknowledgement.

You’ve probably heard them at meetings or graduations. The idea is to take a few short minutes to acknowledge the land where you’re sitting was once home to Native tribes before white settlers came and built cities on top of it.

Williams, an Oglala Lakota citizen with Cheyenne ancestry, is asked to do them a lot. Sometimes, he even does. It’s a chance for him to take the ideas presented in a typical land acknowledgement one step further.

“Don't just acknowledge it. Tell me what you're going to do about it. It's stolen.”

Rick Williams, an Oglala Lakota citizen with Cheyenne ancestry

To audiences small and large in Colorado, he asks, “There's a lot of injustice that went on. What are you going to do about it?”

Now he has a proposition for the whole state and its 6 million residents. He wants to know if you’ll help bring Indigenous people home to Colorado, where 48 federally recognized tribes used to live. He wants them to come back in droves, along with their spiritual brethren — the buffalo, to restore some of what was lost when settlers pushed the tribes onto reservations out of state.

Instead of a land acknowledgement, Williams wants land back.

A shocking discovery

Williams doesn’t want anyone to feel too guilty about not knowing Colorado’s true Indigenous history. Even for someone like him, who spent decades working to champion Indian rights through educational and legal nonprofits, much of the details of what happened to tribes in Colorado between the mid-1800s and the mid-1900s are new.

“I really felt bad because I'm an educated person,” he said. “I should have known some of this stuff. I should have known the history. I didn't. I'm guilty.”

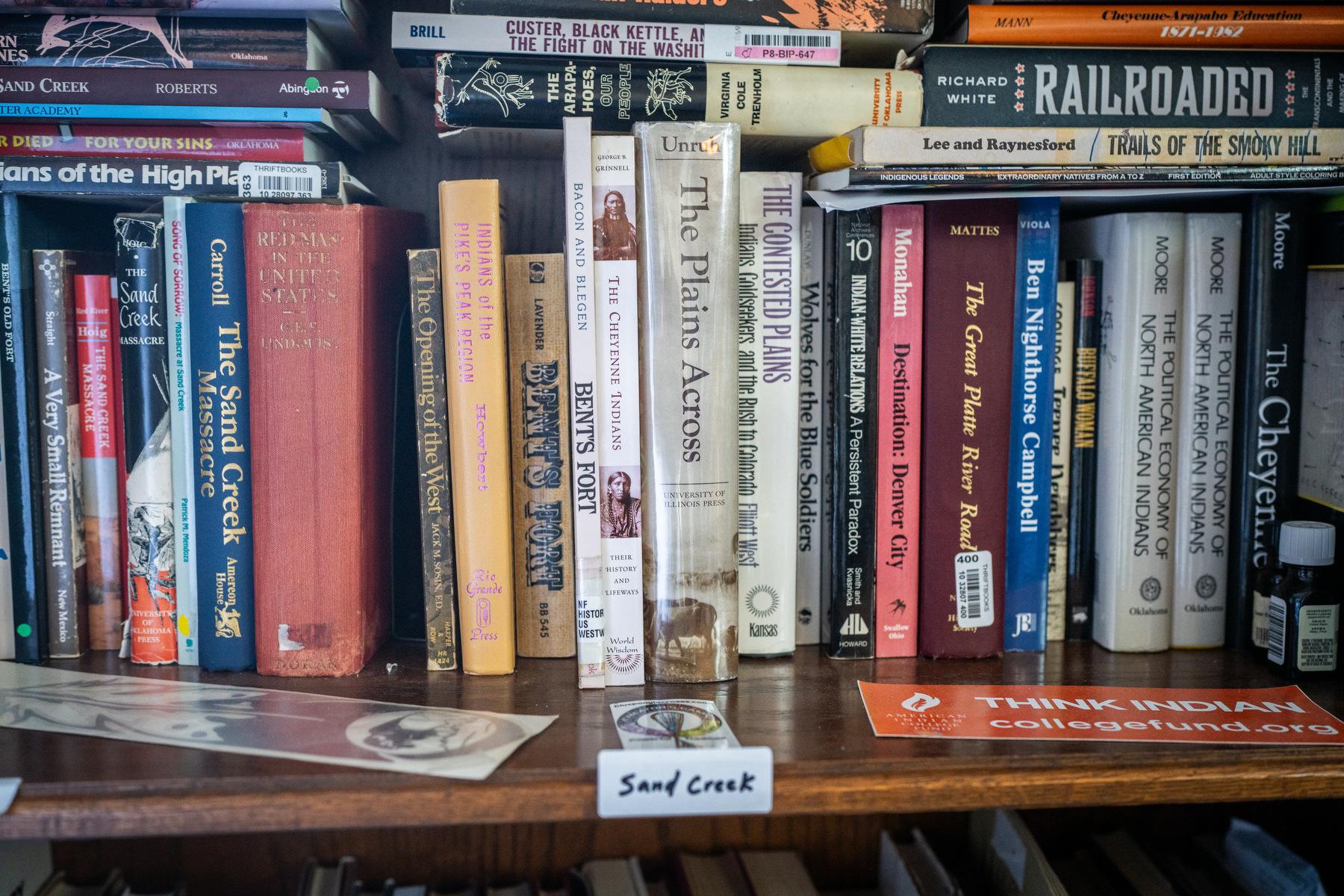

Now in his 70s, Williams has devoted his life in retirement to finding out as much as he can from the perspective of Indigenous people who lived during that time, so he can spread a truer history. He spends hours in his home research library, combing over rare books and documents he’s accumulated over the years. He is uncovering forgotten parts of Colorado’s Indigenous past.

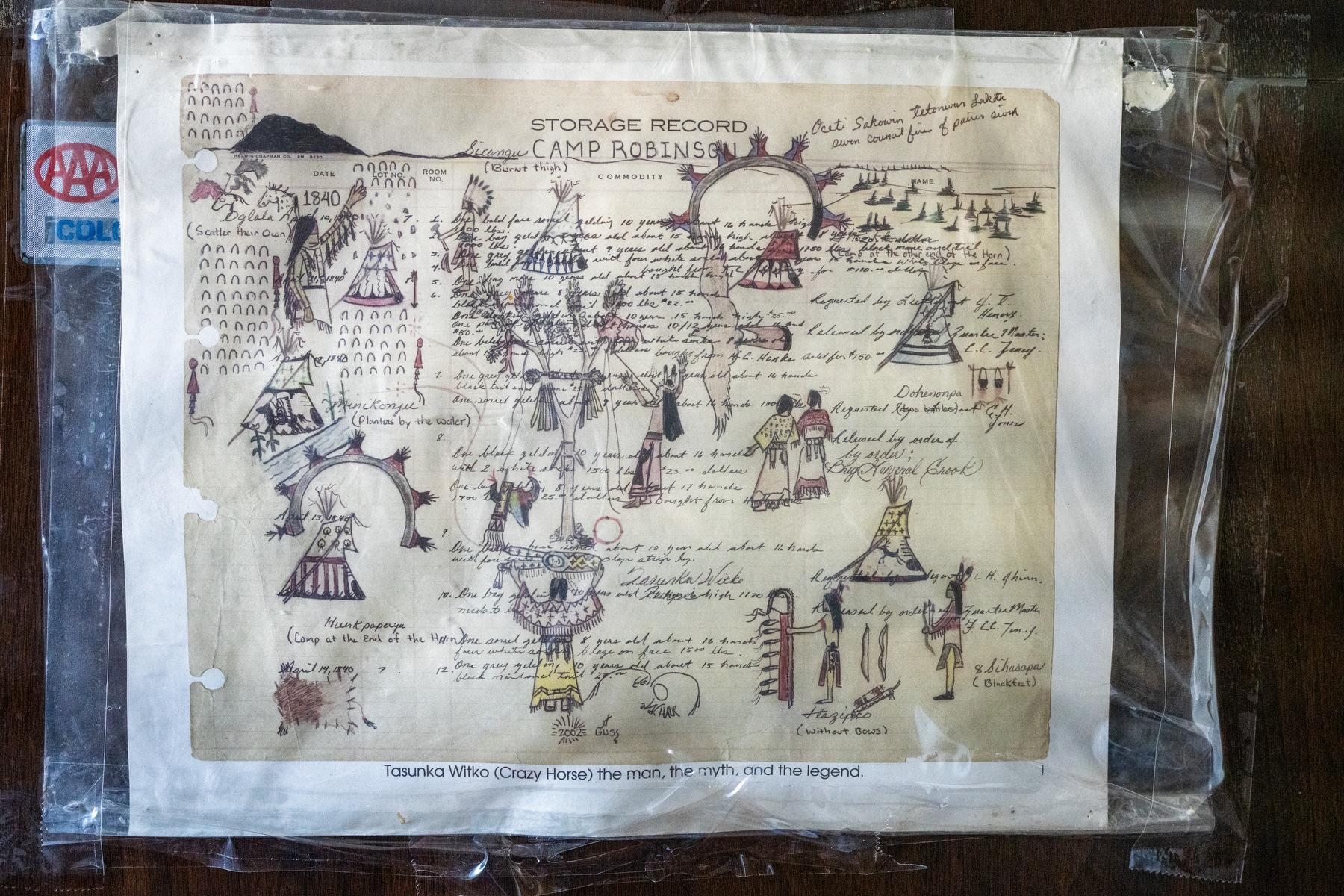

In this home library a couple of years ago, as Williams sat at a table covered with a buffalo hide, he discovered something that truly startled him.

“I run across these things called the proclamations, the Evans Proclamations, and I read the first one and I thought, ‘Oh my goodness, this isn't legal,’” he said.

They were a pair of orders issued in the 1800s by the then-territorial Governor of Colorado, John Evans. The first one directed Native Americans to go to U.S. military forts for protection in 1864, the same year Indians who sought that protection were slaughtered for it at Sand Creek on Colorado’s Eastern Plains. The second proclamation authorized Coloradans to “pursue and kill” Native Americans who didn’t comply with the order to assemble.

What shocked Williams the most was when he figured out that the proclamations were never officially rescinded. That meant, as he sat there reading these orders in 2019, hunting and killing Native Americans who weren’t in compliance was still technically legal.

Proclamations rescinded

Williams made it his mission to get the proclamations nullified. He sent constant emails to members of the state government, all the way up to Governor Jared Polis.

“I'd contacted him for a year and a half, almost on a weekly basis, asking about the proclamations. And I heard nothing,” he said.

A spokesperson for Gov. Polis said Williams met with Colorado Commission of Indian Affairs staff to discuss the Evans Proclamations in 2020.

Some months later, in August 2021, 157 years after the orders were first handed down, and amidst a national focus on racial justice, at the steps of the Colorado Capitol, Polis rescinded them in front of a crowd of people belonging to Indigenous tribes, including the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes that once roamed the same Front Range areas where the Capitol building now stands.

But Williams wasn’t standing triumphantly on the steps that day. Instead, he was in the audience among passersby and journalists watching as the governor signed the proclamations out of existence.

“I was mad,” he recalled. “I was mad because I had done all that work to discover those proclamations and they excluded me from the process.”

Polis’ office did not dispute Williams’ account that he was not invited to speak.

But instead of discouraging him, Williams’ feelings of exclusion propelled him to dig deeper and see what else he could uncover. This time, he wanted help from friends and colleagues.

Williams assembled colleagues to form a group called People of the Sacred Land. They would dig through original records, including treaties among Indian tribes and white people.

Then they would lay out a path forward to make amends.

To understand Colorado’s Indigenous future, we must find echoes of the past

On its face, the confluence of the South Platte River and Cherry Creek is a place for people to relax and find some green space in the middle of Denver’s vast urban landscape.

But for Williams, it is a painful reminder of his ancestry and the systemic erasure of Native Americans in the western U.S.

“It kind of makes me sad when I look at the river and I see all of this stuff here,” Williams said as he sat at the nexus of the South Platte and Cherry Creek last fall. “This stuff has been built, and yet you can walk around here and you'll never see any evidence that there were American Indians here and we were here for 11,000 years.”

Before colonial settlers headed westward, the confluence provided vital resources to the Indigenous tribes that called the area home.

Here, dozens of tribes would follow the buffalo herds that grazed on the banks of the river. They’d sustain themselves by hunting the buffalo or eating the wild crops that grew there, like chokecherries or wild plums.

The buffalo is intertwined with Williams’ quest. To him, the giant, lumbering beast native to Colorado is the most important creature in Indigenous history and its future.

“When the buffalo do well, we will do well. And so if we can help bring buffalo back, we will help bring our people back,” Williams said.

Buffalo populations thrived in the 1800s, when Rick’s ancestors roamed here and camped at the Confluence, even once white settlers arrived.

But manifest destiny changed that — the belief that the United States was commanded by a higher power to expand its dominion across the continent. That mentality pushed people westwards and soon afterwards, hopeful prospectors found what they were looking for: specks of gold in the waters here.

The Gold Rush sent hundreds of thousands of settlers to Colorado

On the Eastern Plains, there’s a replica fort in La Junta that helps tell the story of Indians and white settlers.

Bent’s Old Fort National Historic Site represents the center of diplomacy in Colorado’s Wild West. It’s midway to Kansas, about 200 miles southeast of Denver. It’s part of the Sante Fe Trail, which became a major trade route for Colorado.

Jake Cook, an interpretative manager at Bent's Old Fort, contrasted it with the Oregon Trail, which was more focused on moving families out west.

Instead, Cook said, “Think of the Santa Fe Trail as nothing but a modern highway with nothing but semis going back and forth. This is all about commerce.”

Originally founded in 1833, the fort was like a 19th-century Tower of Babel where French Canadians, French Creoles, eastern settlers, and Spanish speakers from the south all mixed.

Tribes, too, became part of the international trade.

At the fort, tribes had access to guns, horses, alcohol and more available for trade. But to buy those, they needed to tap into their own resource — the buffalo.

“From the native perspective, there's millions of buffalo,” Cook said. “The idea that they might go away someday is just so out of this world.”

By selling the buffalo, tribes became more tethered to white settlers. White trappers brought guns and killed hundreds of thousands of buffalo to sustain the fur trade. They rarely used the whole animal.

The buffalo trade made tribes wealthy, but it whittled down a sacred source of food and it made the animal scarce.

“You have this kind of concept of economic imperialism kicking in where they get so tied into the trade goods and they're getting that it just drastically alters their way of life,” Cook said.

The US makes a play for the land

White settlers also destroyed the buffalo’s habitat with wagons and horses trampling on it, and they wanted the land on the Front Range. They drew up treaties to get it.

Williams and his group found that the deals signed with Indian tribes were often signed under duress.

“Hunger was a very important factor, because after all of everything is destroyed around here, the buffalo are gone, the deer are gone, the elk are gone, there's nothing to eat. And so people were starving,” Williams said.

By 1863, Indians had been in a starving condition for 10 years, especially during the winters, People of the Sacred Land wrote in their report, released in June 2024.

Once tribes did sign treaties, the U.S. government often didn’t live up to its half of the bargain. The U.S. was supposed to pay for damage caused to the land and the buffalo. Williams and his team found that it rarely did.

“The inability of the U.S. government to respond in meaningful time to the white invasion and conflicts on the Plains was a constant problem in this period.”

People of the Sacred Land

The settlers weren’t even supposed to be on Colorado’s Front Range at that time — they were illegally crossing a border into territory that was officially ceded to tribes by the U.S. government in 1834 and 1851.

Still, the Europeans came during the Gold Rush and created settlements like Denver, which was officially formed in 1858.

The U.S. government tried to formalize and legalize its encroachment. In 1861, it introduced the Fort Wise Treaty to take a majority of the Cheyenne and Arapaho land, including places now known as Fort Collins, Boulder, Denver, Colorado Springs and all the towns between them.

The US wanted to usher in a new era of growth in Colorado

“In 1862, the United States government passes the Settlement Act, which opened up land for everybody, millions of acres,” Williams said.

It also passed the Pacific Railway Act of 1862 and the Morrill Land-Grant Acts. These would designate land to railroad entities and higher education institutions, like Colorado State University, on land that belonged to Indians. CSU recently acknowledged that it still profits from the land it was granted, at the expense of Indian tribes.

To get the Fort Wise Treaty finalized, the U.S. government gathered leaders of the Southern Cheyenne and the Arapaho tribes near Lamar, Colorado, along the Santa Fe Trail. But Williams said they were practically forced to take an unfair deal.

“They were told that if they didn't do this, they wouldn't get annuities,” he said. “They wouldn't be able to survive or they would be exterminated. So they were forced to go there.”

Even so, at the treaty conference, only a handful of Cheyenne and Arapaho came. There weren't enough Cheyenne leaders present for the agreement to be legitimate under tribal law. But the 10 tribal signatures on the treaty were enough for the U.S. government to declare it owned most of Colorado.

In the aftermath, the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes were told or forced to move to reservation land outside of the state.

Williams contends that even if the Fort Wise Treaty is considered legitimate, it didn’t actually cede part of Denver. He also draws a direct line from the treaty to the state of Indigenous communities today — reservations are commonly afflicted with widespread poverty, a lack of public services and poor healthcare.

“It's tragic. It's really tragic,” Williams said. “And I think I wish people would understand, and I wish people would be more sympathetic and understanding about this being somebody's homeland.”

American entitlement to the land led to increased violence between settlers and Indians

In 1864, territorial governor John Evans issued the two proclamations that Williams discovered two centuries later: one required Indians to gather at specific camps and the other called for citizens to “kill and destroy” Native Americans deemed hostile to the state.

Using those proclamations to justify their actions, Colonel John Chivington and his soldiers spent hours slaughtering and mutilating hundreds of Cheyenne and Arapaho women, children and elders who had gathered to seek peace with the settlers.

Today, on the windy plains, that site still stands as the Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site.

Signs here outline a brutal hour-by-hour account of one of the darkest moments of Colorado history. But that could soon be erased. An executive order issued by President Donald Trump directs the Department of the Interior to remove monuments, statues and memorials that quote "contain descriptions, depictions, or other content that inappropriately disparage Americans past or living.”

Such an action would unwrite even a modest acknowledgment of the violence that took Indians off Colorado’s Front Range.

Descendants of the massacre have never been compensated, and Colorado and the tribes with ancestral ties to the land still grapple with the Sand Creek Massacre. Many of them have been pushed out of the state after the massacre, into reservation land. And on the smaller areas of land they were forced into, the U.S. put restrictions.

“We can't sell our land without permission of the United States government,” Williams said. “We can't build a home on our own land without permission of the United States government.”

People of the Sacred Land documented that in the decades after Sand Creek, the public discourse around Native people got even more aggressive. Newspapers printed a rallying cry of “Utes Must Go!”, and in Denver, residents were asked if Indians should be moved to reservations and taught to support themselves. The residents shouted back, “Exterminate them!”

A call for restoration

Williams and the People of the Sacred Land group have thought a lot about what it would mean to restore what’s been lost for tribes here. They asked themselves: For a population as large and as diverse as the Indigenous one, what does restoration look like for all of them? How could all this history possibly be made up for? And how can he get non-Native people to want to do something?

“We need to recognize that we did these things, these wrong things to Indian people,” he said. “We need to make amends. We need to do restorative justice, and we have every reason to be doing it because we're living in our land.”

Today, about 100,000 Coloradans identify entirely or in part as American Indian or Alaska Native, and many live in urban areas, mostly in metro Denver and Colorado Springs.

Only two of the tribes with historic ties here, the Ute Mountain Utes and Southern Utes, have reservations in the state, and they’re hundreds of miles from the Front Range.

Williams and thousands of Native people across the nation have been working on a bold concept — it's called land back.

The idea is that tribal entities across the US could reclaim control over some land they once had, and restore their ways of life

Williams is a leader of this movement in Colorado. He is trying to steward real land back, especially on the Front Range. But it isn’t his plan to kick people out of their homes.

“Well, I'm a pragmatic functionalist and I realize that this is never going to change,” he said, looking around downtown Denver. “This is going to be what it is. It's not practical, it's not feasible to displace everybody and everything here.”

Instead, Rick has been talking about the findings of People of the Sacred Land’s massive research project. On conference stages, at local government meetings, at community groups and even one-on-one. He spreads a truer history of Indians here and challenges people to question: What do Coloradans owe Indian people, and how can they help?

People of the Sacred Land have developed dozens of specific ideas about how to restore what was lost. They want the state to protect sacred sites; offer free tuition, room and board at universities built on property taken from tribes; and give tribal members hunting and fishing rights back on public lands, among other things.

But asking governments to deed land back to Indigenous peoples without anything in return has been a tall task.

Right now, they’re focused on one of the state’s most desirable locations

In the 1800s, Boulder was a popular hunting ground for the Arapaho and the Ute tribes. If you pay enough attention, you’ll notice a handful of reminders about their history — a couple of mountains, a handful of roads and the town of Niwot are all named after historic Indigenous tribes and figures.

But soon, Indian tribes that once roamed Boulder could return home.

Fred Mosqueda lives on the Cheyenne-Arapaho reservation in Oklahoma. He often makes the 10-hour drive to Colorado and feels a deep connection to Boulder.

Mosqueda works for the Cheyenne-Arapaho government. His main charge has been to find a way to bring them back to Colorado and steward the land like they did before settlers took it.

“It would be like coming home,” he said. “This was the perfect place to be, as far as wildlife and food. And so… we want to be here again, because it took care of us and we feel that it can still take care of us today.”

“Our ancestral home is here,” he said.

A return is closer than you might expect

Right off Ute Highway in Boulder County, between Longmont and Lyons, there’s a tract of land known as the Cottonwood House. There, an old farmhouse sits behind a peaceful grass meadow and a babbling brook.

Mosqueda has his sights set now on this piece of land, where he plans for Indian people to manage buffalo herds just like they used to.

He’s working with a Boulder County commissioner named Marta Loachamin. Together, they’re in the midst of brokering a deal to lease farmland and housing here at the Cottonwood House to the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma.

Mosqueda said it would bring the buffalo — a sacred source of food, clothing and tradition — back to Boulder County. Buffalo are relatively rare in modern Colorado; wild populations are scarce and domestic herds pale in comparison to the great herds that once roamed Colorado’s Plains.

“They have the land, we have the expertise, we have the animals,” he said. “So together we're going to put a buffalo project together there in Boulder County.”

The Boulder County buffalo project isn’t exactly “land back,” because the tribe will still have to pay to lease the land for buffalo to graze on and for the housing that tribal citizens will live in. But it does represent something greater. It represents a way that two governments — one from Colorado, and one from the tribes – can chart a path forward together.

Loachamin said the deal still has a long way to go before it’s done, and she hopes it’s just the beginning. She thinks that governments with the funds to do so can and should buy land for tribes that want to return to their ancestral homes.

“Just to say we're going to do something or think about it or just start conversation is, for me, not enough,” said Loachamin. “And I feel like now I know what I know now. And so what can I do to move a change forward? And again, to me it's funding and it's policy, otherwise it won't be permanent.”

A spider web of allies

Many people have gotten involved in the land back movement. Loachamin said she learned more about the history and struggles of Indian people through conversations with the First Nations Institute in Longmont and with elected officials in neighboring cities who shared her goal to advance Indigenous rights. Concerned citizens have gotten involved, too, like a group of Indigenous and non-Indigenous residents called Right Relationship Boulder, co-founded by Jerilyn Decoteau, a member of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa, and Paula Palmer, a white woman.

They began with the goal of helping the city of Boulder adopt an Indigenous Peoples’ Day resolution. They’ve become one of Williams’ closest allies in the land back campaign.

“So we have the Indigenous People's Day and they have all those nice ‘whereas’ clauses ‘where therefore’, ‘we shall, therefore we shall, therefore we shall,’” Decoteau said, poking fun at the language of government declarations. “Well, we wanted to make sure they did the Shalls Change signage, do something about education.”

Williams says the movement needs multiracial groups like Right Relationship to pressure governments and ally with Indigenous communities.

“Within the last maybe 10 years, the consciousness of the people in Colorado, they've become more aware of what happened, enough so that they're starting to create opportunities for Indian people to come back,” he said. “Boulder's got the Right Relationship group, and they're bringing Indian people back because they recognize that this is their homeland, but it's only happening in isolated places.”

Another is in Denver, where Williams and Mosqueda are part of talks about the prospect of a cultural embassy and political gathering place for tribes to be located near Denver International Airport. It would serve as a gathering space and cultural hub for people with ancestral ties to the Denver area, and allow for government-to-government relationships between the capital city and tribes like Mosqueda’s that are otherwise located out of state.

The next generation will choose how to continue the fight

Like Williams, Mosqueda is in his 70s. While they each spent their lives advocating for change, they know their efforts will primarily benefit the next generation.

“It is going to be the young people that live here,” Mosqueda said. “It is going to be the young people that's going to maybe actually get the rewards of what we're trying to begin here.”

The bureaucracy of the government moved quickly to take land from Indians. But, ironically, Williams knows that getting legislative action now is an uphill battle — especially in Colorado, a state that has no active Indigenous lawmakers among its 100-member body.

“I have to be patient. I think any kind of legislation or any kind of initiatives like that is going to take three years, probably before we even fully realize our work that we've started here,” he said. “It's going to be 20 years. I won't be around then, I hope.”

Even if tribes are given land back, Williams said it only covers a fraction of the atrocities committed against tribes native to Colorado. People of the Sacred Land have made 56 recommendations overall; the most controversial is probably the idea of a reparation fee on all future real estate deals in Colorado.

Williams recognizes that sheer power of will won’t achieve their goals.

“We have to have compassion from the state government and from the federal government to make it happen,” he said. “Without them supporting it, it ain't going to happen.”

And even more than that, he says he needs Coloradans — non-Native ones, especially — to understand the true history of tribes on this land, to care about what happened to them and want to make it right.

But now, seeing the work he’s helped start with People of the Sacred Land alongside his peers, and seeing the possibility of tribes returning to Colorado, a novel emotion has washed over Williams.

“For the first time in my life, I've seen positive things happening for Indian people, and that is a real joy for me,” he said. “Like I said, I've been in this struggle for a long time. I've been fighting for Indian rights from the time I was 19 years old, and I see the potential.”

Story by Paolo Zialcita

Produced by Shelby Filangi

Edited by Rachel Estabrook

Audio produced by Paolo Zialcita, Rachel Estabrook and Pedro Lumbraño

Photos by Hart Van Denburg