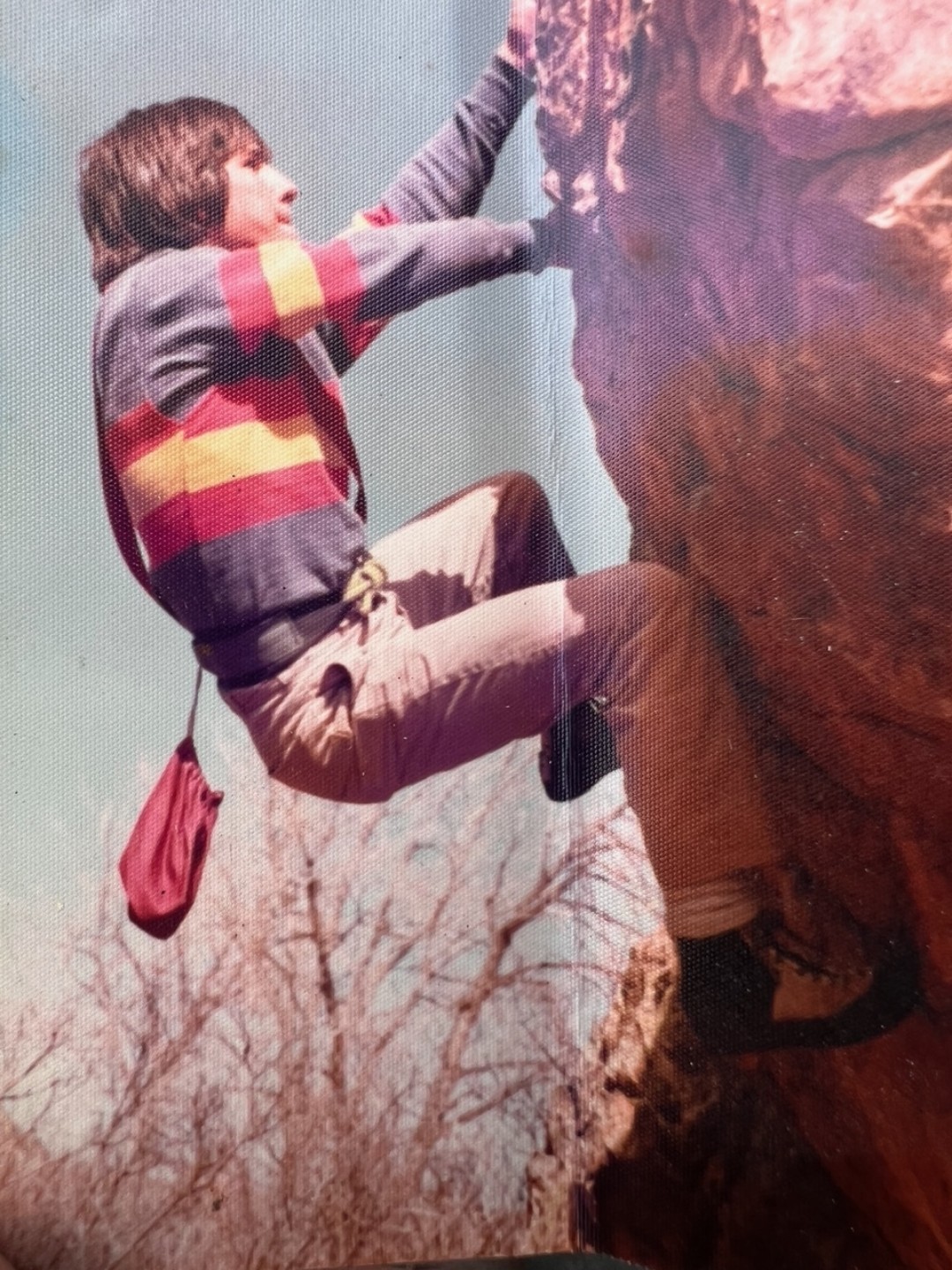

Astronaut John Herrington was clinging to the International Space Station 250 miles above the Earth when he realized that his days spent rock climbing in Colorado would come in handy.

“When you step out of the hatch for the first time, you hang on kind of tight,” he said, “You're in this constant free fall around the Earth, and you can't tell how fast you're going. And you realize the tighter you hang on, the more tired you're going to get. And so you hang on very lightly and you move around.”

“And so my rock climbing experience — climbing along the Font Range, climbing El Dorado, Boulder Canyon, climbing up in Turkey Rock, and those places — that rock climbing experience directly related to doing a spacewalk.”

Herrington, the first enrolled member of a Native American tribe to fly in space, spent his boyhood in Colorado Springs. Though his family moved to Wyoming after his 6th grade, he returned for college at the University of Colorado Colorado Springs, and in many ways considers Colorado home.

“I really consider Colorado a place I grew up, and I have a lot of friends and a deep tie to the state,” he said.

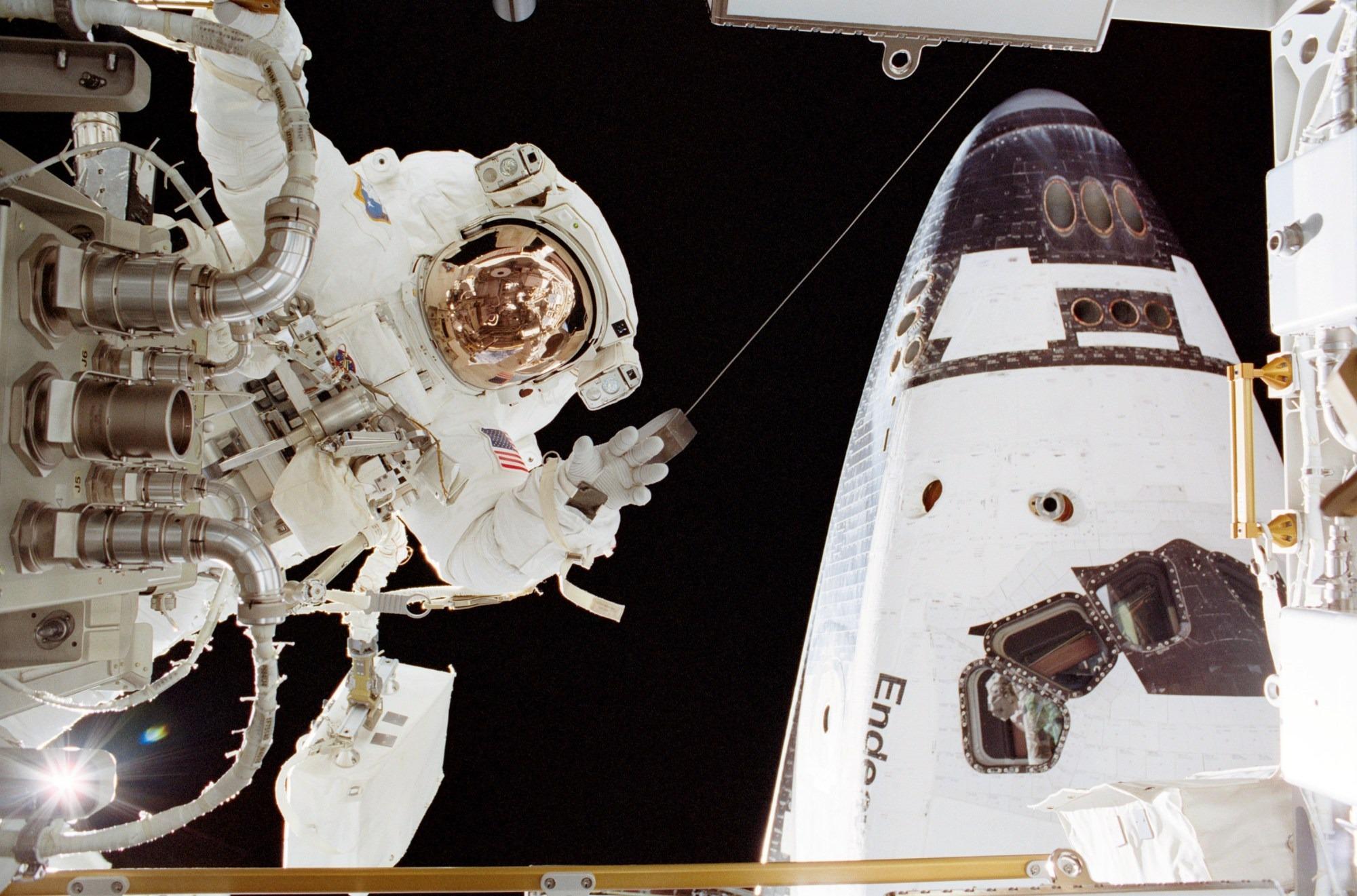

Herrington is a citizen of the Chickasaw Nation, which is headquartered in Oklahoma. After serving as a Navy test pilot, he went to space aboard the shuttle Endeavor in 2002, and later worked on the investigation of the shuttle Columbia disaster. After leaving NASA, he earned a doctorate in education, and now advocates encouraging Native youth to pursue science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) careers.

Remembering a boyhood in Colorado

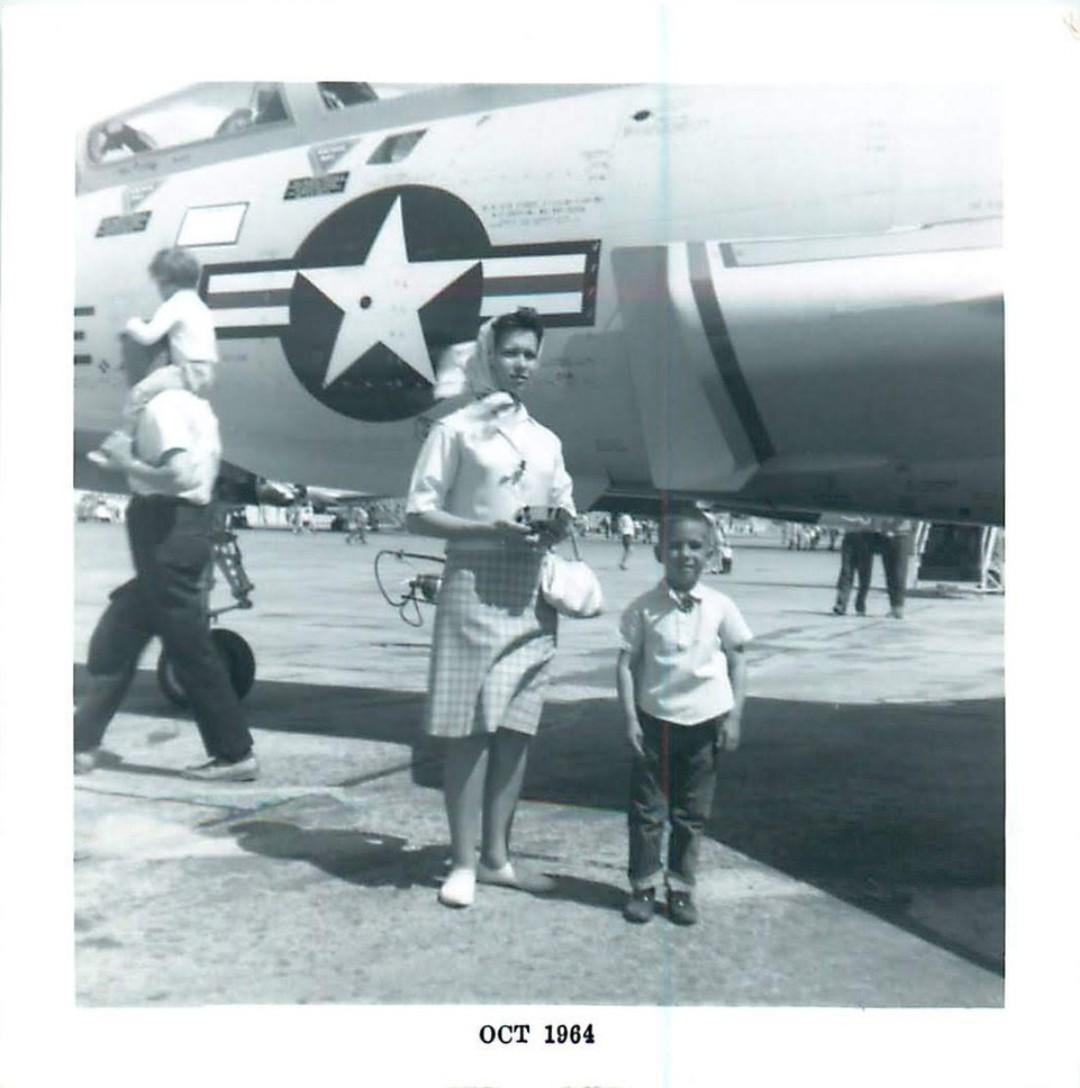

Herrington was born in Oklahoma, but his family moved to Colorado when he was about a year old.

“We did a lot of stuff in the mountains. Used to go four-wheeling up around Chalk Creek, Mount Princeton, Mount Antero. My dad belonged to the Colorado Springs Mineralogical Society. We used to hunt for crystals,” he said.

“My first ski lesson was at the Broadmoor back when I was about 10 years old,” he said.

After his family moved to Wyoming and then Texas, Herrington returned to Colorado and enrolled at UCCS for college. It was during that time that he took up rock climbing,

“I enjoyed rock climbing because there was always a goal,” he said. “And so I started climbing, and kind of quit studying. I put more effort into climbing than I did into education and got kicked out of school for low grades my second semester.”

Herrington even found work as a climber, surveying the cliffs for the construction of Interstate I-70 through Glenwood Canyon.

He eventually returned to UCCS, graduated with a degree in applied math, and joined the Navy, where he became a test pilot.

From building I-70 to building the ISS

Herrington blasted off aboard the space shuttle Endeavor in 2002, with the mission of building the International Space Station. As the first enrolled member of a Native American tribe to go to space, he brought along mementos to honor his heritage: an eagle feather that had been given to him by an elder with the American Indian Science and Engineering Society, as well as a flute made by a Cherokee flute maker.

Just two months after his safe return to Earth, the space shuttle Columbia broke up on re-entry over the skies of Texas. Herrington spent months working on debris recovery, an effort that was aided by Native American fire crews.

“They treated every piece of element they found from the shuttle as a living piece. Not an inanimate object, but something they held in great reverence. And I took great pride in working with those folks,” he said.

Thanking a Colorado teacher and refocusing on education

Herrington retired from NASA and turned his attention to education. He said he was inspired by the people who encouraged him along the way. In particular, he tells the story of a Colorado Springs teacher who made a lasting impression on him.

As Herrington’s 6th grade year was coming to an end, he said, his parents planned to move the family to Wyoming. His teacher gave him a going-away gift: a bracelet. The gesture meant so much to Herrington that he carried that bracelet with him through college, the Navy and even to NASA.

“And so when I flew in space, I took it with me,” he said.

Later, when he returned to UCCS to receive an honorary doctorate, he invited his former teacher and told the story to the crowd.

“And I said, some teachers really make an impression on a student and not because of the knowledge matter that they know, but the way they are, the person, how they care about people. And I said, ‘I had a person like that in my life and she's right here, Toodie Royer, and I flew this bracelet, 5.6 million miles in space and I want to give it back to you and thank you for being a good person and being a good teacher.’”

“Oh, I started crying. She was crying. Yeah. It's nice to thank people. Thank somebody that made a difference in your life. For sure,” he said.

Herrington’s doctoral dissertation studied how to inspire Native youth to become more involved in STEM.

“When I talk to native kids, I like to say that our ancestors were exactly that. They were engineers, they were botanists, they were chemists, they were astronomers. They knew the world around them intimately,” he said. “It's in your DNA. It may be a different way of learning, but if this is what you want to do, go down that path.”

His current mission brings him full circle, back to his elementary school days in Colorado. And the advice he gives to anyone, Native or other, is straightforward.

“Don't let anybody tell you you're not capable of doing something,” he said.

November is Native American Heritage Month, a time to celebrate the traditions and stories of Indigenous communities in the United States.