Part 1: Why is the federal government spending millions on aerial geological mapping in Southern Colorado?

“Ancient volcano guts that got heated and munched over billions of years.”

That’s how U.S. Geological Survey geophysicist Patricia MacQueen describes the geology of the Wet Mountains, along with other nearby parts of southeastern Colorado.

She’s one of many scientists working on the USGS’s Earth Mapping Resources Initiative or Earth MRI project. It’s a program aimed at mapping the planet’s surface and subterranean landscape, including in the Wet Mountains.

Right now China is the primary source for materials used in everything from cell phones to missile guidance systems. That means international politics could lead to glitches in the supply chain. So the federal government is pushing hard to pinpoint domestic sources of rare earth elements and critical minerals.

But those old rocks MacQueen talks about don’t always contain valuable minerals according to her USGS colleague, research geophysicist Tien Grauch.

“Having minerals that are economic in an ore deposit, for example, is a very unusual thing,” she says. “You have to have lots of geological processes come together right in one place and they're mostly unique. That's why they're hard to find.”

Searching for minerals from the air

Geophysicist Angela Farr uses a laptop inside a gleaming blue helicopter at the Salida Airport. She works for one of the contractors collecting data for Earth MRI. The computer’s screen glows with graphs.

“Basically, my job is to make sure that the equipment's set up and collecting good data,” she says. “And then to do a quick data check when it comes in, make sure it's complete and then send it off.”

She points to a large box behind the pilot seat.

“It has five crystals in it, four pointing down and one pointing upward,” she says. “That measures the radiation off the top couple of inches of the earth. And then what's coming from the sky.”

A long white boom called a stinger sticks out from the front of the helicopter. At its tip is a red bulb holding gadgetry to measure variations in the landscape’s magnetic fields. She says people always wonder what’s inside it, but, “they're always disappointed.”

She opens it up.

“One thing you'll notice is there's no metal,” she says. “It's all polyethylene screws and wood because we don't want to introduce a local field.”

Jennifer Hare is another contract geophysicist working on this study. She says that’s why the instrument that passively measures the earth’s magnetic field is out on the stinger

“You can't mount the magnetometer on the helicopter because the helicopter has metal,” she says. “You can't have metal objects near it because that creates noise in your sensed magnetic data.”

Speaking of noise, there’s plenty of the audio kind when the pilot takes off. The rotor spins making a loud racket and creating a whirlwind.

Hare explains the helicopter’s flight path.

“We're trying to stay at a constant height and we have laid out a grid of lines for him,” she says “So it's kind of like mowing the lawn. He's got a grid of lines he’s following.”

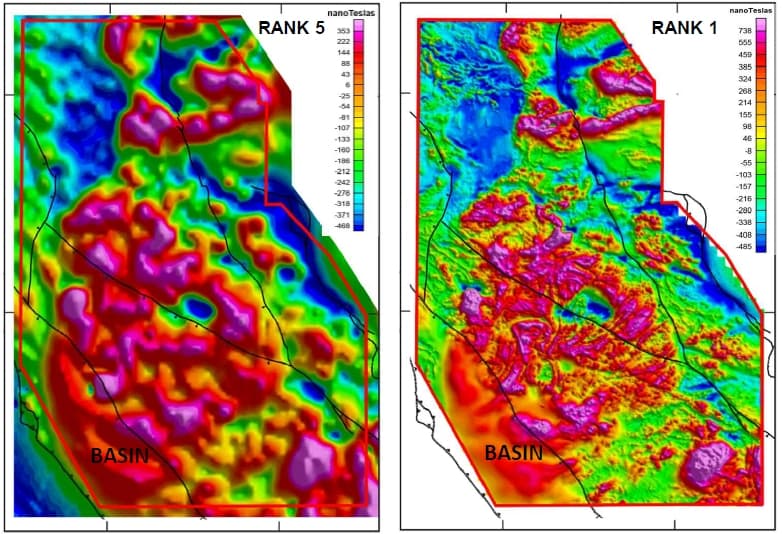

The pilot crisscrosses the survey area at a low altitude, flying east and west and then north to south, so the instruments pick up information on lines just 150 meters apart.

This kind of airborne data gathering isn’t new, Hare says. “It originated back in World War II, we used magnetometers to hunt for submarines.”

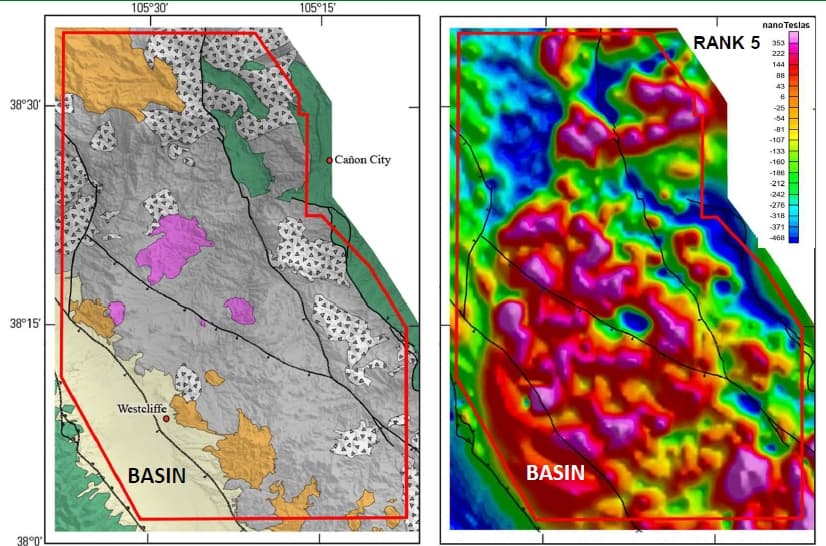

Maps created from older data are often lower resolution and don't always match up with each other though, according to Hare. That’s why this new data is so useful. She and other scientists get the information ready to send to the Earth MRI project team, where it will become part of maps for this area.

Grauch and MacQueen take the data from the helicopter surveys and prepare it for public use - including by industry and academia. MacQueen says it’s a long process - but’ll expand geological understanding.

“The great thing about this data is it's going to be around for many, many, many years,” MacQueen says.

Ground truthing involves actually looking at the rocks in real life

Then there’s the work of ground truthing, when geologists go into the field to verify what is on or in the ground by actually looking at the rocks. Geologist Ben Magnin, who worked for USGS at the time, takes out a small hammer to demonstrate this at a cliff face in a nearby canyon.

“The first thing the geologists will do will go up to the outcrop and they'll bang on the rock and try to pull off a sample,” he says. Then they'll look at it to determine what the rock type is and how it corresponds with the data.

Magnin follows up his low-tech rock hammer work with a pocket-sized box called a magnetic susceptibility meter to measure the properties of the rock. He places it against the outcrop, pushes a button and the instrument beeps.

“We just beep it once on the rock, once out in the air, and then it spits out a value,” he says.

The reading is low.

“This would not produce a magnetic anomaly in the airborne survey that we're flying,” he says.

If the data had shown a magnetic field in this spot, the researchers would know it’s from something underground and not from the surface. The ground truthing helps confirm what they found.

The scientists are processing data collected by the helicopter in Southern Colorado to prepare it for public release as soon as possible, but there's no anticipated date yet.

This kind of work including overflights and ground truthing and even a satellite partnership with NASA is happening across the country, from Alaska to Wisconsin and Florida to continue expanding and improving Earth MRI’s mapping and data.

- Finding underground water from 100 feet up in the air: How aerial sensing systems chart El Paso County's natural resources

- The Spanish Peaks in Southern Colorado are a piece of the geological puzzle of why the High Plains are so high

- Aquifers: The groundwater in Colorado’s wells and how it gets there

- Do you know where your well water comes from? A look into aquifers in Southern Colorado