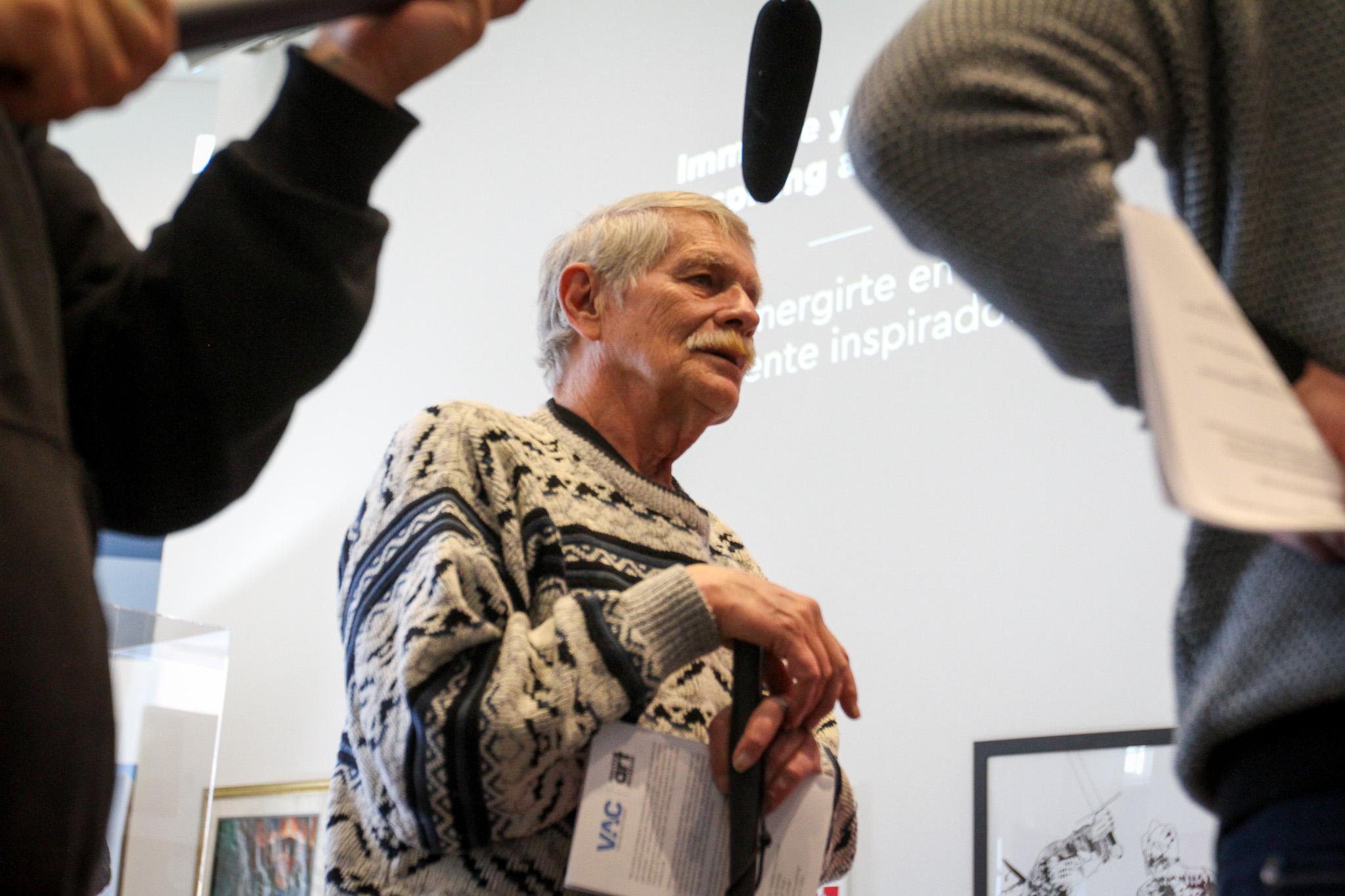

Artist and military veteran Jim Stevens was shot in the head in the Vietnam War. Bullet fragments remain inside his body, which have led to lifelong migraines. In 1993, the injury led to a stroke that made Stevens legally blind.

He has what he calls “pinhole vision,” viewing the world almost frame-by-frame.

"If you're three feet away from me, I can see one of your eyes. But I have to look up to find your eyebrow," he explained. "I have to look around your face to see what you look like."

Limited sight has taught him patience. Art has also been his teacher.

The carving of a virtue

"I didn't do anything for probably two years (after the stroke), except get divorced," Stevens said.

In the divorce, he gained custody of his two youngest daughters.

"After a couple years, they said, 'Dad, you know, you've always loved art. You should get back to it.' And my first response was, 'I can't see.'"

But Stevens' daughters were relentless. His youngest, Megghan, urged him to carve something for her.

"She wanted me to do a wizard head," he said, "out of ancient Mammoth ivory."

Before he lost his eyesight, he was a skilled scrimshander. With much encouragement, he decided to give carving another try.

"It took me over 900 hours, and I think about halfway through, I got frustrated. I threw it across the room," he recalled.

But his daughter wasn't going to let him off the hook.

"She walked over and picked it up, brought it back, set it down on the table in front of me and said, 'Daddy, you promised not to quit.' I felt about an inch tall and went back to work."

Now, nearly 30 years later, Stevens is a dedicated artist. He's even created two new painting techniques that earned him the Veterans Affairs’ National Gold Medals for Fine Art.

A work using one of these signature techniques now hangs at the Denver Art Museum. It's part of "Beyond the Military: From Combat to Canvas," a show Stevens helped organize.

The portrait of a jazz guitarist is painted on seemingly countless strands of monofilament, a medium Stevens invented after a backyard mishap.

"My 6-year-old grandson at the time, I heard a cry for help," Stevens said.

He remembers going outside, where he found his grandson with a toy fishing pole and a rat's nest of line.

"I thought, ‘Yeah, right. The blind guy's gonna try to help the 6-year-old untangle this,’" Stevens said. "But as I was trying to help him, the clouds went over, and I was looking at the monofilament on my fingers, and it just looked like it rippled and moved, even though it didn't. And I couldn't get that out of my head."

After months of trial and error, Stevens figured out how to use monofilament as a canvas.

From Combat to Canvas

Stevens is the director of Denver's Veterans Arts Council. He helped get over a dozen works by Colorado veterans into the Denver Art Museum.

It's part of the museum's Community Spotlights program, which showcases local art.

"There's so much incredible talent, and we're so lucky to be able to highlight the wealth of what we have here in Colorado," said Nistasha Perez, public engagement manager at the Denver Art Museum. "In this exhibition alone, we have everything from photography to leather purses, painting, embroidery. There's so much going on."

"85% of the artists that you're seeing here are disabled," Stevens added.

"They had a choice," Stevens said of the injured veterans. "You can curl up in a ball and just sit there and anguish, or you can do something. And they chose art."

"Every year I have (veterans') friends, or a family member, that comes up to me and says…if it weren't for the program, they're not sure if their loved one would still be around," he added.

"It makes me realize that, while we don't offer art therapy [commonplace now in the VA], we are the next step. We are that next level for our veteran artists."

But many of them struggled with their shifting identity. It wasn't necessarily easy for them to become creatives.

"We do have some of the toughest, orneriest, SOB veterans I have ever dealt with," Stevens said with a laugh.

But they've all landed in the same boat — as artists.

"They chose to do something creative, rather than let their disabilities impact them."

"Beyond the Military: From Combat to Canvas" is at the Denver Art Museum through February 2026. Museum hours are Thursday through Monday, 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. and Tuesday 10 a.m. to 8 p.m. Admission starts at $19 for adults 19 and older. There is a free admission day on Tuesday, Dec. 9.