Rob Fisher is no longer surprised by the sight of moose near his house in Silverthorne.

Since moving to the community along Interstate 70, he’s caught the hulking deer relatives browsing foliage along bike trails and roads, plus his neighbor’s backyard and the local Target parking lot. It's common enough that he's careful to watch for moose around blind corners and walks with his dog.

Those encounters led him to delve into the natural history of the massive land mammals. That's how he learned that Colorado wildlife managers have spent decades engaged in a highly successful effort to boost moose. After multiple reintroductions, around 3,500 moose now wander every corner of the Colorado Rockies, from Steamboat Springs to the San Juan Mountains.

Moose are hungry herbivores known for eating more than 60 pounds of plant matter per day. Given those voracious appetites, Fisher wrote Colorado Wonders with an ecological inquiry: How are wetlands and other habitats handling all these ungainly ungulates?

“I’m curious as to what environmental impact moose might have made,” Fisher said.

Why Colorado reintroduced moose in the first place

Colorado wasn’t always so flush with moose.

Sightings were rare during most of the last two centuries. A recent survey of historical and archaeological records, however, found the mammals occupied Colorado and other parts of the southern Rocky Mountains before and during the arrival of European settlers. Those records include males, females and juvenile animals, suggesting Colorado once supported a viable moose population, not only isolated males wandering in from other states.

The research was led by William Taylor, an associate professor and curator of archeology at the University of Colorado Boulder. He took on the project after noticing multiple news articles and government websites claiming moose were “invasive” or “non-native” in Colorado. He turned to archives to prove the animals were, in fact, present before reintroduction.

“If we're building narratives around animals that are anchored in the past, I want those facts to be correct,” Taylor said.

By the 1970s, however, Colorado wildlife managers determined excessive hunting had eradicated the species. It launched a restoration effort in the winter of 1978, led by Dick Denney, the former big game manager for the Colorado Division of Wildlife, an agency now known as Colorado Parks and Wildlife.

A 56-page plan written by Denney claimed the project would provide residents with the “non-consumptive aesthetic values” of restoring a native species and let hunters eventually harvest animals with “unique trophy value and particularly good meat.”

It also proposed Colorado’s North Park region as an initial release area since it had ample willow and other potential food sources. The plan, however, declined to discuss any ecological risks, only mentioning relationships between moose and other species “may range from negative through neutral to positive.”

One of the initial capture operations was featured in an episode of “Mutual of Omaha’s Wild Kingdom,” a long-running nature and wildlife TV show. It follows Denney — clad in a green jacket and a Burt-Reynolds-calibre mustache — to the Uinta Mountains of northern Utah, where wildlife managers darted a cow moose from a helicopter. Another helicopter then lifted the sedated animal to the nearest road before it’s trucked 350 miles east to the release location.

At the end of the episode, Marlin Perkins, the original host of the program, triumphantly proclaims: “Moose have now been reintroduced to the wilds of Colorado!”

Judged by Denney’s original goals, moose reintroduction has been a wild success. After obtaining an initial batch of two dozen Shiras moose from Utah, Colorado wildlife managers brought additional batches into the state until 2010.

Colorado now has one of the few growing moose populations in the western U.S. The species has also continued to expand into new territories, providing ample wildlife viewing and allowing the state to sell roughly 670 moose hunting licenses in 2025. Each of those permits costs more than $2,750 for out-of-state residents.

“We’ve helped them along a little bit, but, generally speaking, they’ve expanded on their own and pioneered new habitats,” said Andy Holland, Colorado’s current statewide big game manager.

Overpopulation in Rocky Mountain National Park

There is at least one place where moose have likely had a less beneficial impact: the Kawuneeche Valley on the western side of Rocky Mountain National Park.

Since 1987, David Cooper, a senior researcher emeritus focused on wetland ecology at Colorado State University, has studied the valley, where the Colorado River snakes across a mostly flat, mountain clearing until it reaches Shadow Mountain Reservoir near Grand Lake.

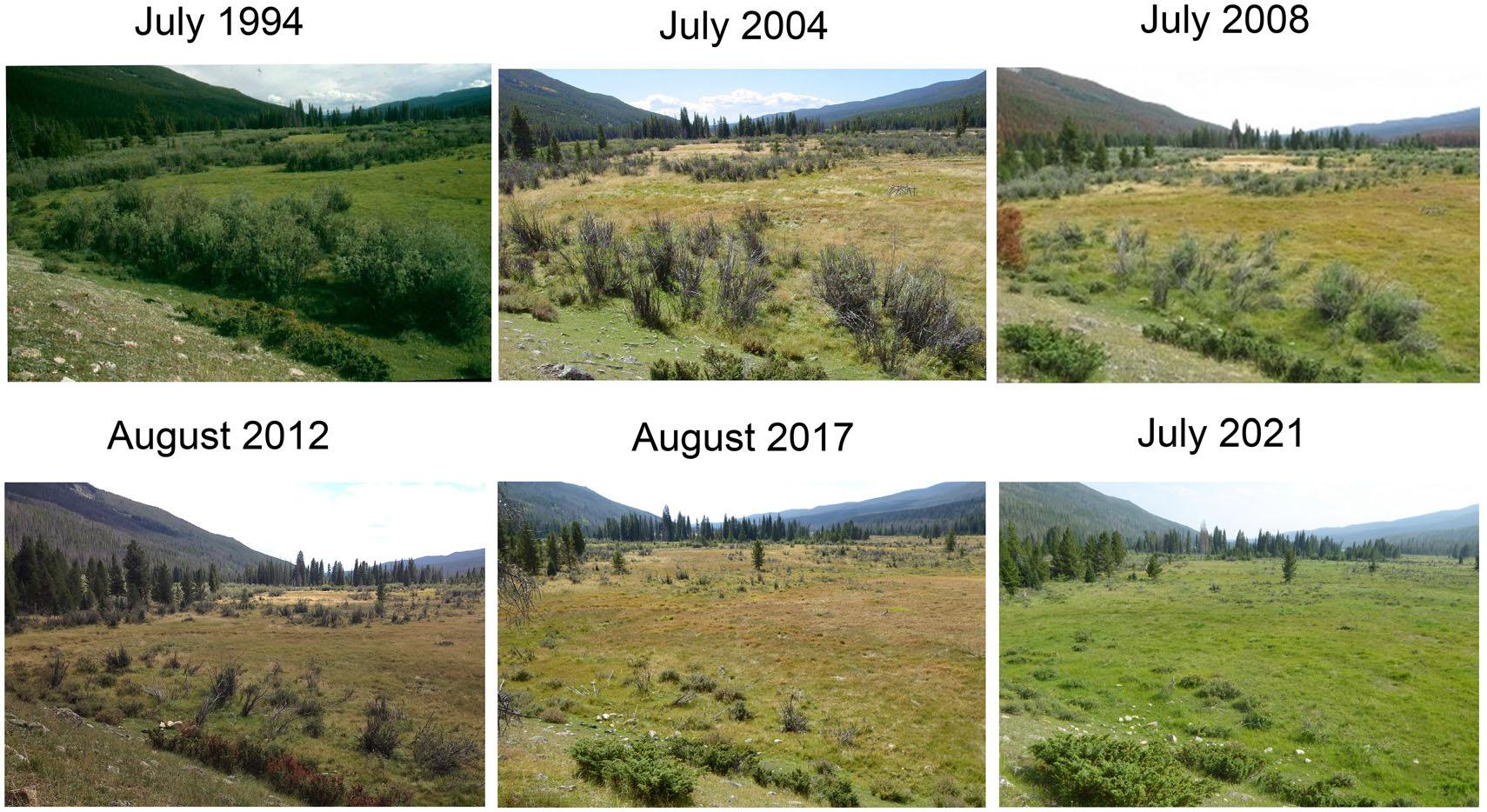

He remembers the area as a complex of interconnected beaver ponds. On a recent bitterly cold morning before Thanksgiving, it was clear the valley is now a lumpy grassland packed with the dry skeletons of once-abundant willow plants.

“If you look around, it’s like a willow graveyard,” Cooper said.

A recent paper co-authored by Cooper blames the collapse primarily on elk and moose, along with a drying climate and other factors. It notes the park’s moose population has exploded from a single known individual in 1980 to more than 140 three decades later, according to aerial surveys. As those animals have thrived, willows, their preferred summertime food source, have struggled to survive.

The older ecosystem remains intact within a handful of fenced areas built to exclude moose and elk. Inside one erected 14 years ago, a beaver dam spans the width of the Colorado River, pushing water out across the landscape. Revived willows also provide shelter for birds and other wildlife.

“I’ve seen river otters, fox, coyotes,” said Isabel de Silva Shewell, a wetland ecologist with Rocky Mountain National Park. “Great blue herons like to come here, too, and enjoy the pond. It’s pretty cool.”

Holland, Colorado’s big game manager, said other moose habitats across the state haven’t experienced such radical ecological collapses. Those moose populations, however, are also kept in check by hunting, which is strictly prohibited in national parks.

Cooper said moose once faced a range of threats in the park: wolves, grizzly bears and Native American hunters. Without those pressures, he said, their numbers have exploded, and he hopes the park acts quickly to save its rapidly declining willow habitats. He’s also not convinced Colorado’s recently reintroduced wolves will multiply quickly enough to offer a solution.

“It's just the worst-case scenario,” Cooper said. “People appreciate the animals, but the bigger story of the ecosystem decline and what’s gone along with it needs to be told more clearly.”

Rocky Mountain National Park is now developing a plan to manage its moose population and protect its wetland ecosystems. It plans to hold an informational session about those ideas on Dec. 8 at 6 p.m. after opening a web portal to gather public comments

The park has relied on culling to control its elk population. Park staff could kill moose, pushing back against a restoration that’s been so successful, people might have to step in to manage the impact.

Colorado Wonders

This story is part of our Colorado Wonders series, where we answer your burning questions about Colorado. Curious about something? Go to our Colorado Wonders page to ask your question or view other questions we've answered.