Colorado’s path to statehood was anything but straightforward. The process stretched across nearly two decades, collided with national politics and reflected deep disagreements about power, representation and belonging.

That winding story anchors “38th Star: Colorado Becomes the Centennial State,” an exhibit at History Colorado in downtown Denver. As Colorado approaches its 150th anniversary in 2026, the exhibition examines how the territory finally became the 38th state, and why it almost didn’t.

Historian and exhibition developer Katherine Mercier, who curated the exhibit, says many visitors are surprised by how uncertain the outcome really was.

“We had to try very hard in many different ways over nearly 17 years to become a state,” Mercier says. “And even then, it almost didn’t happen.”

Shifting motivations

Colorado first pursued statehood in 1859. Each attempt that followed failed for different reasons, shaped by changing economic realities, population shifts and political priorities.

Early on, cost played a major role. Gold miners, some of the territory’s most influential residents, opposed statehood because it meant paying state taxes. Remaining a U.S. territory allowed Congress to fund the government instead.

Other tensions followed. Rivalries emerged between Denver elites and miners. Residents debated the promise of railroads. The population in Colorado fluctuated. National politics, including the Civil War and Reconstruction, repeatedly altered the odds.

At the federal level, support also shifted. President Abraham Lincoln backed Colorado’s bid for statehood. After his assassination, President Andrew Johnson vetoed it. Colorado leaned Republican, and Johnson opposed adding Republican votes to Congress.

Statehood became a tug-of-war — not only between Washington and the territory, but among Coloradans themselves.

Who was excluded, and who pushed back

The exhibit features groups often marginalized in statehood narratives: Indigenous tribes, Hispano residents of southern Colorado, Black Coloradans and women.

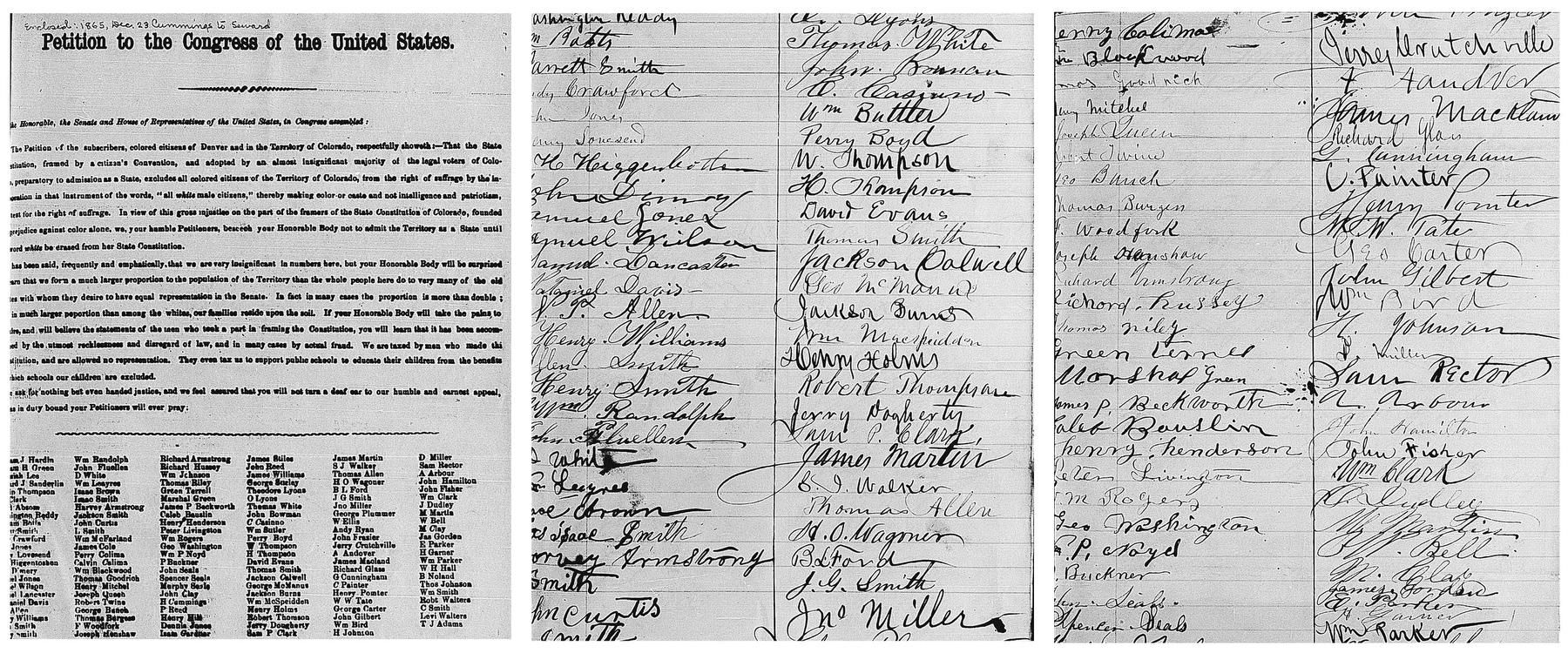

One of the clearest examples comes from 1865, when a proposed state constitution added the word white to voting eligibility. That single change stripped Black men of the voting rights they had previously held in the territory.

Black community leaders organized in response, with some businessmen circulating a petition demanding the word be removed. The exhibit displays all 137 signatures from Black men who signed it.

Their efforts delayed statehood once again, as Congress debated whether to admit a state that excluded Black men from the vote.

Objects that shaped Colorado — literally

Some of the exhibition’s most revealing moments come from physical objects rather than text.

A surveyor’s chain, used in 1861 to map parts of what would become Denver, shows how settlers translated land into measurements — and measurements into streets. Surveyors used the chain to establish grids that still define the city today.

That same process shaped Colorado itself. Although the state appears rectangular, Mercier notes that Colorado actually has 697 sides, the result of 19th-century surveying errors and the limits of the tools used at the time.

Another centerpiece is the original proclamation signed by President Ulysses S. Grant on Aug. 1, 1876, formally admitting Colorado as a state. Mercier points out that when Grant began writing the document, Colorado was still a territory — and by the time he finished, it was a state.

Treaties, displacement and survival

The exhibit also examines how Colorado’s creation affected Indigenous peoples.

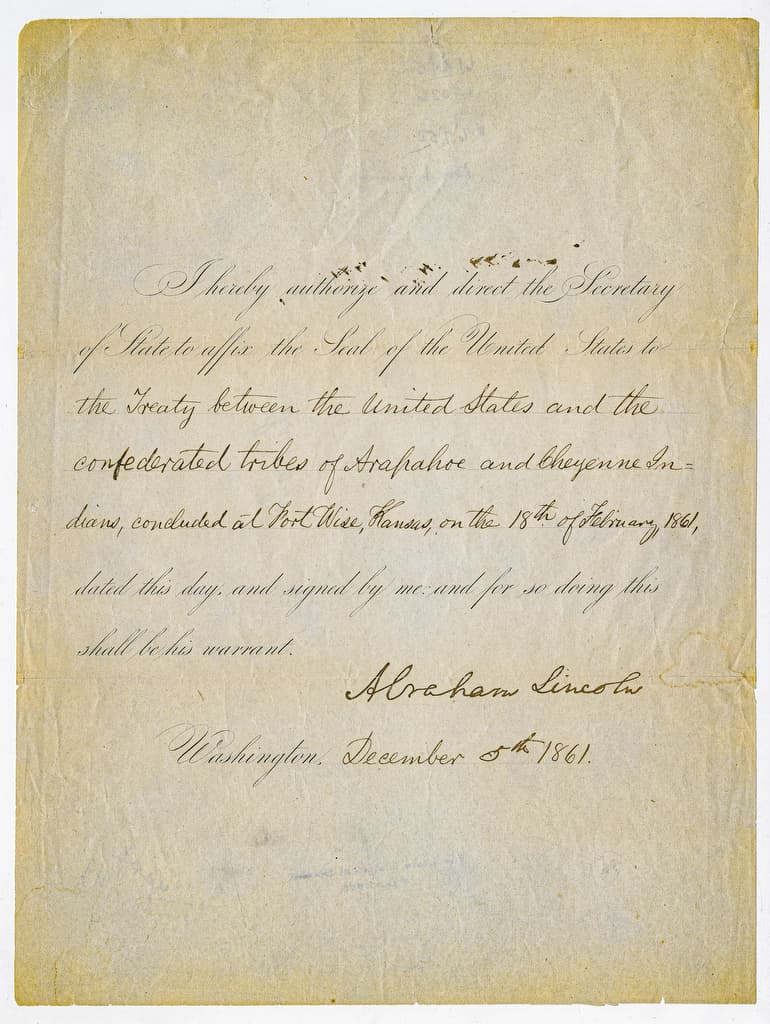

Documents such as the Treaty of Fort Wise, signed in 1861, show how land was taken from the Cheyenne and Arapaho, dramatically shrinking their homelands and restricting their movement. Mercier emphasizes that treaties often served as tools to remove Native people from land rather than to protect them.

The exhibition highlights Indigenous leaders who warned early Denver settlers about flooding along Cherry Creek — advice settlers ignored until floods devastated the area.

These stories run throughout the gallery, underscoring that Colorado’s path to statehood came at great cost to people who lived on the land long before it became a territory.

Celebration and reflection

Celebrations erupted even before Grant signed the proclamation declaring Colorado a state. Newspapers called it a victory. Parades filled Denver. Decorative bunting sold out across the city.

But Mercier hopes visitors leave with more than a date or a designation.

Colorado’s statehood, she says, “wasn’t inevitable.” It required persistence, conflict and people willing to push — or resist — change. Everyday decisions about rights, representation and belonging shaped the state that exists today.

At the end of the exhibit, visitors encounter a question: How can you make a difference in the next 150 years of Colorado statehood?

The debates that shaped Colorado in the 1860s — over land, resources, language and political power — still echo today.

In that way, “38th Star” is not only about how Colorado became a state. It’s about how the state continues to be shaped.