This is part of an occasional series looking at aspects of Colorado’s faltering economy.

At first glance, Columbine Place, an office tower in Denver, doesn’t look so bad.

The lobby isn’t grand, but it’s been updated — it’s clean and welcoming.

Still, it’s a building that no one wants.

The buyer defaulted, and the lender determined the building wasn’t worth taking. The maintenance on the 44-year-old tower is more than the property is worth. Ground-floor retail tenants have all left, leaving paper on the windows.

It is a microcosm of the challenges facing large sections of downtown Denver. There are many old office towers that aren’t appealing to businesses anymore and can’t easily be converted to apartments.

“So what do you do then? I don't know what the answer is,” said Alison Berry, a vice president of CBRE, a commercial real estate broker. “I think that it's going to be a long time until we figure out what to do with them.”

But at the other end of 16th Street, near the vibrant Union Station area, it’s a totally different dynamic. She doesn’t have enough space to lease.

To the southeast of downtown, Cherry Creek North is basically totally leased. Berry said it has the highest rents in the state, but the vacancy rate there is 0.5 percent. That’s not a typo.

“One of the lowest vacancy rates in the country, and that just shows that people are willing to pay up,” said Berry.

A tale of two downtowns

Interviews with elected officials, downtown businesses, and commercial brokers show that the economics of office and downtown are far more complex and nuanced than they appear on the surface. Denver is a tale of two downtowns: in lower downtown, or LoDo, there’s a vibrant economy, retail filling a lot (but not all) of the space, families, workers and travelers admiring the Christmas decorations along the newly opened 16th Street.

It’s the polar opposite of upper downtown, close to the state Capitol, where outdated, drab towers sit mostly empty or totally vacant, and millions in tax dollars are being invested to prop up properties, like the Pavilions mall. Even the most positive booster of Denver admits it will be a long time until the area recovers.

The vacancy rate in downtown Denver offices is 37.7 percent, per the latest report from CBRE. That’s roughly three times higher than pre-pandemic levels. But it feels emptier than that, as few people come into the office every day.

The struggle is national. Portland is investing $7 million on incentives to convert office-to-residential projects as the city deals with historically high office vacancy. In Austin, an estimated 25 percent of office buildings are vacant, and the private Downtown Austin Alliance is experimenting with giving artists and entrepreneurs cheap, temporary rent space to test new ideas.

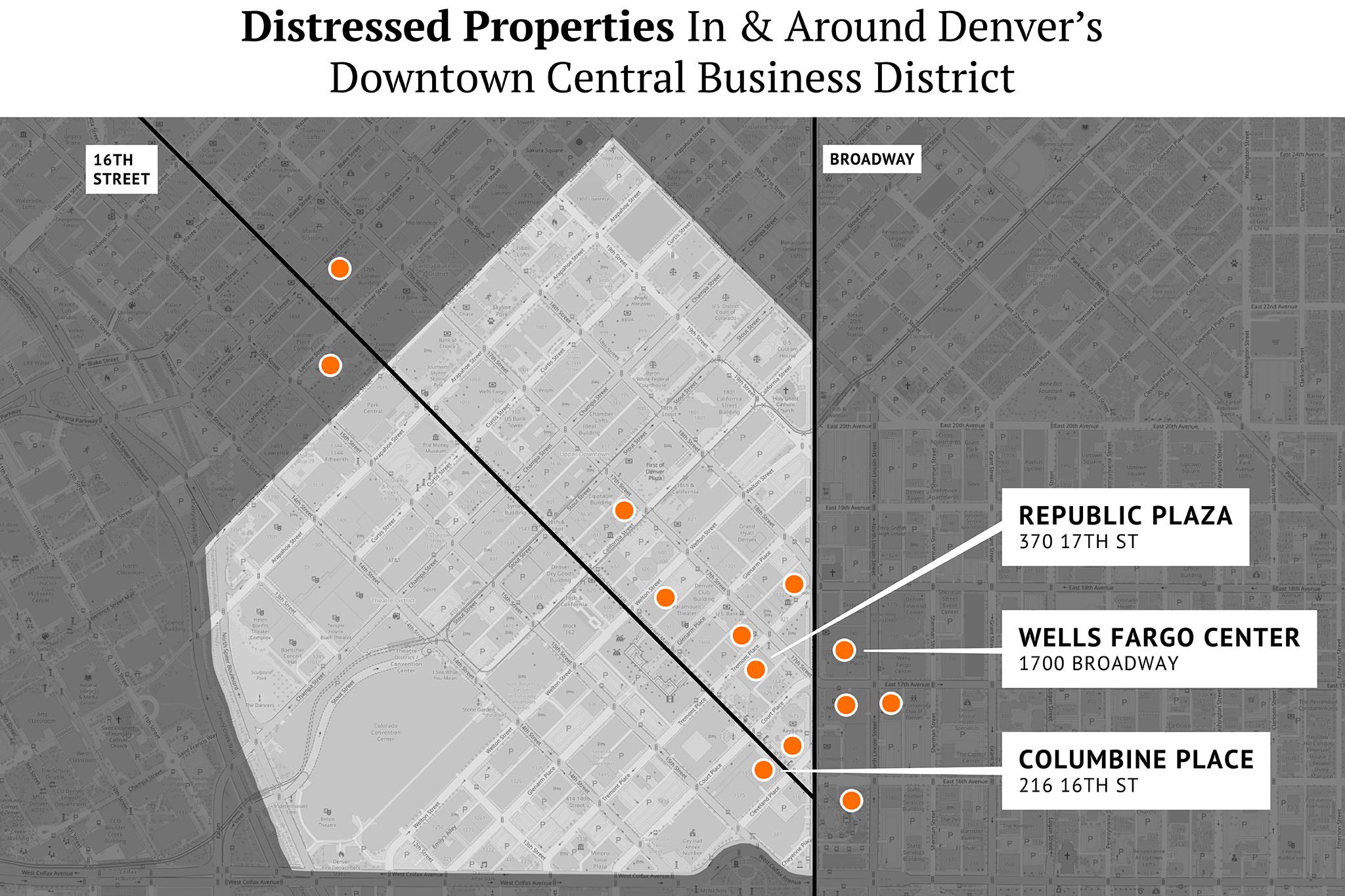

Back in Denver, more than 5 million square feet of office space in downtown is “distressed,” basically in some form of foreclosure, according to a count kept by Thomas Gounley, editor of the news site Business Den.

The problem has accelerated in recent years as businesses have allowed leases to expire. Some buildings are selling at an 80 percent discount from pre-pandemic prices.

“These last couple of years, we've seen a number of foreclosures downtown where it goes to auction, nobody else bids, so the lender takes it,” said Gounley. “This obviously doesn't exist in the abstract, so somebody has to be losing hundreds of millions of dollars on some of these transactions.”

Many of the investors are out-of-state companies based in places like Chicago or Los Angeles, as well as big banks like Wells Fargo, which are losing money on buildings they bought or financed before the pandemic.

It’s also a civic problem, what to do with all these buildings no one wants, that create a drag on the local economy with vacant ground floors and empty offices above.

LoDo, meanwhile, has a lot of new high-end offices around a revitalized Union Station, which connects directly to Denver International Airport. It also has old Denver charm and beautiful historic buildings.

“There is a flight to quality,” said Berry, the CBRE broker. “I lease a building right at Union Station. It's the highest gross rent downtown because our real estate taxes are on the high side, and we are 99 percent leased. And if I had five more floors, I could lease them.”

In the 1980s, it would have been unthinkable that LoDo would be more desirable than upper downtown. The towers around the Brown Palace Hotel were the center of oil and gas economic dominance in the city. LoDo was a collection of dilapidated brick industrial buildings that no one wanted.

Walter Isenberg is the CEO of Sage Hospitality Group. He had an office in LoDo in the 1980s.

“That was before it was LoDo; it was just low,” joked Isenberg.

Eventually, Isenberg moved up to upper downtown, 16th and Welton, but recently moved his offices back to LoDo, above the Milk Market. He credited Denver Mayor Mike Johnston for his focus on public safety, cleaning up encampments and assigning downtown-specific police officers.

“In order to get people to come to a city, it has to be clean and safe,” said Isenberg. “And I think that the feeling of safety is stronger in LoDo for a lot of reasons, not the least of which is we spend about $3 million a year on private security.”

The security investments are showing signs of paying off. Overall, crime downtown has dropped 27 percent since peaking in 2021. Violent and property crime, specifically, are down about 50 percent in 2025 compared to 2021, according to data from the Denver Police Department.

Isenberg said the retail and amenities and pro sports, and the A-line to the airport are a powerful draw for businesses in lower downtown.

“We have several office buildings, a part of our mixed-use projects. We're fully leased, effectively, fully leased.”

So what about the future of upper downtown?

Many of the towers were built in the 1970s and early 1980s — during a boom in mineral prices that led drillers to lease millions of square feet. They clustered around 16th and 17th Street near the Capitol and the Brown Palace Hotel.

The city had to essentially save the Pavilions mall, using tax dollars funneled through a nonprofit to buy the distressed property.

Ground-floor retail in many of the surrounding buildings is more often empty, making leasing the property much more difficult. The L-line RTD train that only circles upper downtown doesn’t connect to the airport, and is closed for renovations anyway. Crime and vagrancy are far more visible.

And the gray metal and glass buildings are ugly, to some anyway.

“Every generation hates the architecture of their grandparents,” joked U.S. Sen. John Hickenlooper.

Before he was mayor of Denver and governor of Colorado, he was an unemployed geologist turned real estate developer and restaurateur, converting dilapidated space in LoDo in the 1980s.

Hickenlooper sees parallels between Denver’s 1980s downturn and today. “History doesn't repeat itself, but it rhymes, as somebody said.”

His own mother wouldn’t invest in his brewpub in LoDo. He was rejected by dozens of banks before the city stepped in to help fund the conversions of empty brick buildings to lofts and restaurants and retail. Few at the time could see his vision for the area.

And now, businesses and the city must come up with creative solutions 10 blocks uptown. He praised the taxpayer-funded purchase of Pavilions mall and office conversions as an example of how cities can step in to help.

In his day, it was an extraordinary investment in sports stadiums and a new airport that set the foundation for what LoDo has become. But he said the things that made Denver attractive then are still true today. Proximity to the mountains, a great climate, an entrepreneurial economy.

The Denver Downtown Development Authority has approved more than a dozen projects, totaling $165 million, including a grant to convert the historic Petroleum Building, next to lowly Columbine Place — from 12 floors of office to 178 residences.

Some local investors are taking advantage of the rock-bottom deals in Denver. Last month, Westside Investment Partners purchased a 12-story office building at 15th and Curtis Street at an almost 70 percent discount from its 2019 sales price. And the company, based in Greenwood Village, announced plans to convert an upper downtown building into apartments.

But almost none of those have finished yet, and many offices are just not well-suited for such a conversion. Many don’t make financial sense without even more city investment.

While it may be difficult to envision what to do with vacant office buildings downtown, that doesn’t mean it’s doomed, according to Hickenlooper. Someone will find an idea for what he called “these big empty shells.”

"I hear these people saying that downtown's dead and it'll take 50 years to come back. That's nonsense.”

Colorado’s economy is flashing warning signs. Job growth has slowed to a trickle. Layoffs are inching up. The housing market is in a slump. Both the state and its biggest population center are struggling to plug massive budget holes. On top of all that, the longest government shutdown in history was weighing on the economy.

The big question, though, is whether all the bleak data points to something more serious: recession. And the answer is complicated.

Colorado Public Radio takes a look at what those warning signs might mean through the new series Silent Recession. Read more stories in the series here.