Lauren Zobec compared her kids’ first experience with a landline phone, a turquoise cylinder device that arrived at her east Denver home in December, to aliens learning how to talk.

“They were holding it way out here,” said Zobec, a nurse and the mother of two boys, gesturing with her hand in front of her. “They didn’t know how to talk. They didn’t know how to answer it. And then when they had a phone conversation going, they didn’t know what to say.”

Zobec, like thousands of other parents across the country and the globe, it turns out, is trying to delay the introduction of a cell phone to her kids for as long as possible.

A large and growing body of research shows that smartphones for early adolescents have been linked to higher rates of depression, obesity and poor sleep. Early kid access to social media alone has been linked to cyberbullying and bad behavior.

But that doesn’t mean parents don’t want their kids connected to their friends and family.

Hence, what’s old is now new again and skyrocketing in popularity across the country, particularly among parents seeking alternatives for kids.

Zobec spearheaded a neighborhood landline pod that has grown to more than 100 families — all from the same elementary school. She touched a nerve.

“When I started texting some friends that I wanted to get a phone, and my phone started blowing up from people I didn’t even know saying, oh I want in on this, I want in on this,” she said. “Clearly, people were looking for something.”

The founder of Tin Can, a landline phone company, went through a similar thing 14 months ago.

Chet Kittleson and a few friends had an idea to introduce landlines — well, landline phones connected by cords using the Internet — to kids around his Seattle neighborhood.

He didn’t know it at the time, but Kittleson was prototyping something that was about to explode.

“I would go to a house, I would set it up, I would meet the parents and I would tell them how it all works,” he said. “Oftentimes, when I was doing the install at a house, by the time I left, I would have five or six text messages from other people, and they’d say, ‘Hey, how can I get one of these?’”

That’s his company’s founding story. A little more than a year later, Kittleson said, Tin Can’s growth — in actual call volume — is “100 times” bigger now than it was in December, with a burgeoning backorder list and demand from people in all 50 states and across the world.

The company is now taking orders to have phones delivered in the late spring.

“When we were kids, our first social network was the landline. They (kids now) don’t have that,” said Kittleson, 38, and a father of three. “We're actively more aware of some of the challenges of cell phones and the Internet in the pocket of a kid. And so we're pushing that age back, and the more we do it, the more we create this sort of new problem where, okay, great, you don't have a cell phone, but now you have nothing and that's not good either. Now you feel isolated, and you're not learning how to use your voice and all of that.”

Plus, it’s a common gripe from parents, Kittleson said, that they get sick of being their kids’ executive assistants.

Arranging playdates, texting parents and organizing summer camps is exhausting. The ability for a kid to hop on the phone with another kid and ask them to hang out is liberating for parents, Kittleson said.

In these early weeks with a landline for both of her kids, Zobec agreed.

“It’s sweet that they’re having these connections and they’re feeling the independence,” she said. “Jake, when he first got it, was calling all of his friends and a couple of times they set up playdates … where like 10 of them would show up and play soccer. And that’s exactly what we wanted.”

Where did landlines go, anyway?

The departure of the landline started when people started buying cell phones in the early 2000s, and in 2007, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services started putting out reports on the percentages of American homes that lived with cell phone connections only.

A 2024 report, which technically was looking at the last half of 2023’s numbers, found 76 percent of American adults and 87 percent of American children lived in wireless-only households. Between 30-44 year-olds, that number was roughly 90 percent.

The precipitous ditching of the landline was so swift that there aren’t many official advocates for them left in the country.

Even many new homes aren’t equipped with the old copper wiring to have a landline jack, Kittleson said. A few lobbying groups, including the AARP, advocate for safety and access for vulnerable people in emergency situations, like the Los Angeles fires, and how landlines can be more reliable than an overloaded (or burned down) cell phone tower.

Even USTelecom, a broadband lobbying group based in Washington, D.C., didn’t have much to say about the trend of shifting from mobile to landlines among parents.

“No matter how people connect, what matters is that they have the best, most reliable, and most secure networks in the world to make that connection,” said Daniel Henderson, a spokesman for USTelecom. “Unlike the copper-based landlines from the 1900s, most landlines today are running on modern, IP-based networks, which means they’re more secure and have the added benefit of stronger protection from things like illegal scams and robocalls.”

Phones for a new generation

The Tin Can company caters to kids. Its multi-colored plastic phones, some in the shape of a tin can, come with phone numbers, but require adults to approve the numbers that can call and be called. Once the device is purchased, kids can call other kids with a Tin Can, as long as they’re approved, for free. For $10 a month, kids can call any number, including grandma, their parents’ cell phones or the fire department, but those numbers, too, have to be approved by the grown-up in the Tin Can app. Anyone can call 9-1-1 with or without a monthly subscription.

Kittleson said they designed it this way to thwart spammers or marketing people from reaching kids.

“People identified there was a real problem with the way that our kids are being raised right now, and we need a solution. And I think that this Tin Can style phone is currently being seen as one of the great things that you can say yes to,” he said. “I think it’s why we caught fire.”

Kittleson’s grand experiment hasn’t been without bumps. There were so many Tin Can phones that went online, literally, on Christmas Day that the call volume jumped 100 times from even the day before. And even though Kittleson hired support staff and prepared for it as much as they could, there were outages across the country.

He was opening presents with his family, and his phone went off, and he had to launch into software crisis management.

Sarah Sing, a Seattle mom of a 3rd grader, lives on a boat with her daughter and got a Tin Can phone that she’s able to carry around when they travel. During the holiday break, they brought the phone out of state to visit relatives and it allowed her daughter to continue to connect with friends.

“My kid’s in third grade, and she was asking for a phone this year,” Sing said. “It gives them a feel of how we grew up as kids. Really, it’s about keeping my daughter away from social media.”

Dr. Benjamin Mullin, a child psychiatrist at Children’s Hospital of Colorado who specializes in child anxiety, said he’s seen a surge in interest from parents about landlines in attempts to bolster friend and family connections for kids that studies show can directly thwart anxiety caused from too much time on the Internet.

Data show that anxiety among kids really spiked between 2019 and 2021 — during the COVID-19 pandemic. But Mullin points out that, perplexingly, those anxiety rates haven’t come down as the world has returned to normal.

“Anecdotally, running an anxiety program here at a large children’s hospital, the anxiety is more frequent and the severity of it is more intense than it was 10 years ago,” Mullin said. “If I had to guess, it was the social isolation, the lack of daily interactions, that help people feel comfortable and happier and less focused on the things that aren’t right in their lives.”

Mullin said specifically, there is data correlated directly with the amount of time young people spend on devices with their levels of anxiety, depression and behavior problems. The more time they’re on screens, the less life-satisfaction they have and the worse they function in school and in their social lives, he said.

Mullin said the lack of social experience and interaction in the younger years can linger like a hangover into the young adult ones.

“It’s like they often really struggle with how you even navigate the basic aspects of social interaction, how you start a conversation with someone you don’t know, how you end a conversation effectively,” he said. “Not to mention how you navigate day-to-day conflict with your peers, your friends. I think all of those things are harder when you haven’t had to practice them when your brain is really developing.”

Rosanna Breaux, a psychologist at Virginia Tech who specializes in children and adolescents, said that cell phones and social media, inherently, aren’t all bad for all kids. For some who feel particularly marginalized or lonely, they can find community, even if it’s not local.

But she noted it should be controlled and monitored, so that once those kids grow up, they can thrive.

“We see this clinically all of the time, from a social standpoint, a lot of the basic social skills are really lagging behind, those soft skills that end up being needed for occupational success, relationship success,” she said.

Breaux also said there are new data showing that even infants, when they see their parents on a screen, perceive it negatively because of the lack of engagement.

“It’s the resting scroll face,” she said.

A replacement for smartphones, for now

I’m in the east Denver pod of parents embarking on the Tin Can experiment. My kids, 6 and 9, have consistently used the phone most days since Christmas break. The older one is more adept already, but even the younger one will call his grandparents and loves to pick up the yellow cylinder when it rings — even if it does violently get jerked out of his hand by his older sister.

They are learning etiquette. They are learning how to ask questions and how to answer, how to wait for the social cue when someone needs to hang up and the niceties of saying goodbye — particularly to an adult.

Among the perks of listening to their real analog conversations is how they come up with things to say, without the wretched distractions of a FaceTime call, which can devolve into trying to make a grandparent’s face into an emoji or one of the kids amplifying the screen and staring at themselves in slackjawed wonder while grandpa is talking.

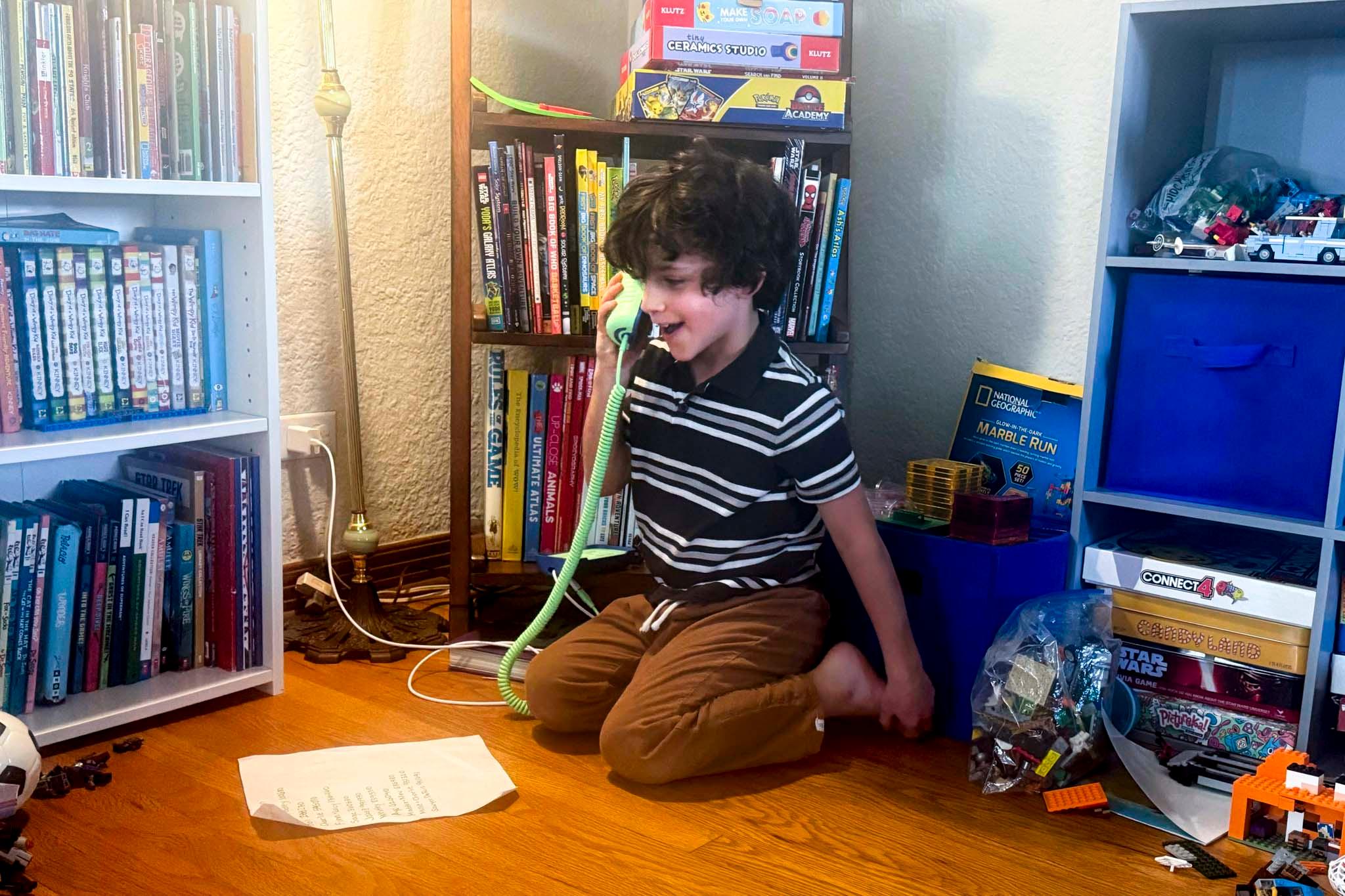

At the Wiseman house in east Denver, the kids’ phone is surrounded by piles of books and toys and games. The two boys, Miles and Jules, have numbers written out in scratchy kid scrawl and they have to take turns with the landline.

The father, Jordan Wiseman, whose inside sales job requires him to be on the phone all day long, said it’s kind of like watching baby giraffes learn how to walk.

Zobec is worried about the longer game. She wants this to be an actual replacement for a smartphone for as long as possible. She hopes other neighborhood parents, especially her kids’ friends’ parents, wait until the teenage years to introduce smartphones — and especially social media — to kids.

She hopes the landlines aren’t a blip, like a toy kids get for Christmas and then are sick of by the summer.

“All of us know the research, we know how detrimental cell phones can be and I think we can hopefully push it off until 16 and that’s the recommendation,” she said. “But it takes all of us because as soon as one person gets one, then it’s 'mom, everyone has a phone.’ We need to stick together as parents.”