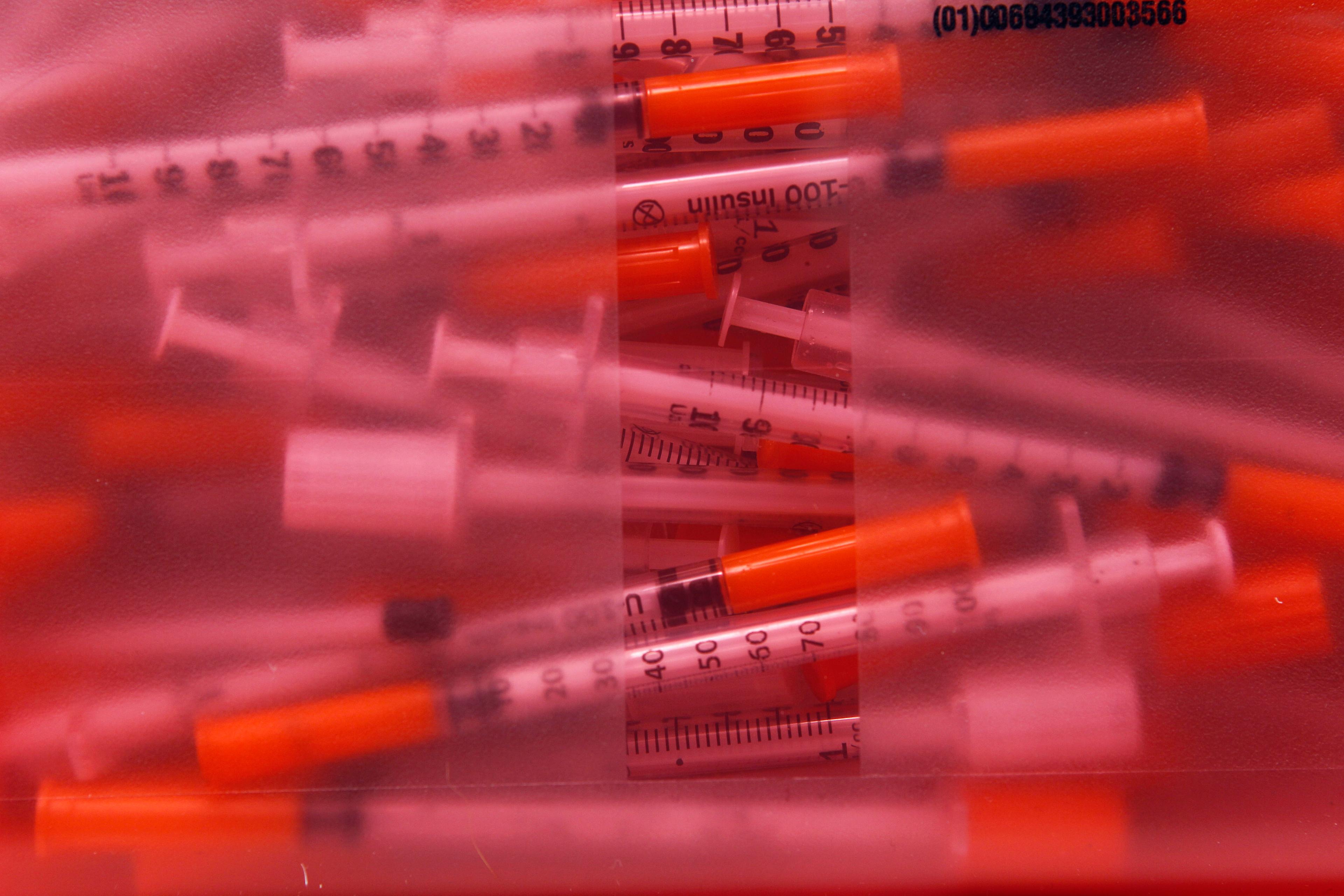

Pueblo’s City Council voted Monday to discontinue free syringe exchanges that have been in place for a decade. The decision comes on the heels of other U.S. cities reconsidering similar programs meant to slow the spread of communicable diseases amongst intravenous drug users.

Council members’ 5-2 vote on a new ordinance that bans the practice in the city. The majority argued the exchanges had littered the city’s public spaces with unreturned used needles, while the two minority members argued other methods should be explored to reduce dropped syringes before ending the program.

“Why do we have to sweep (Bradford Elementary School) every single morning and every single afternoon? Because there are used needles on the campus, where children are,” said council member Joe Latino. “I’m going to be very candid about it right now. I want needles out of Pueblo.”

Access Point Pueblo has operated an exchange since 2014, with the Southern Colorado Harm Reduction Association opening a second exchange in 2017. In addition to syringe exchange, the locations provide overdose prevention medication and training, STI testing, and other services.

Representatives from Access Point said their exchange had dispensed 345,000 syringes in the previous nine months. About 72,000 of those syringes were unaccounted for, meaning they were either not returned to local nonprofits or not placed into specialized disposal boxes located around the city.

Councilwoman Sarah Martinez, who voted against the ordinance with Councilman Dennis Flores, said she recognized the littered needles as a problem that needs to be addressed. But she “wholeheartedly” disagreed that ending the exchange would actually result in fewer needles.

“If we aren’t willing to listen to the experts and use data to make our decisions and instead make decisions based on our emotions or fear-mongering or just because we don’t like something, then I am fearful for the future of our community,” Martinez said.

Residents against the ban spoke for a combined total of more than two hours, compared to the less than 15 minutes of public comment in favor.

Several of those opposed to ending the needle exchange identified themselves as Pueblo-based medical professionals and pointed to research from organizations like the Centers for Disease Control and American Medical Association, which suggest that increased intravenous drug use resulting from the ongoing national opioid crisis has led to a widespread increase in infectious diseases like Hepatitis C and HIV.

Research shows syringe exchange programs can lower the transmission of such diseases by 50 percent, according to the CDC. Users of the exchanges are also five times more likely to enter drug treatment programs.

“I’m not disputing the science,” said Councilwoman Regina Maestri before she voted to end the exchange. “Nobody’s saying (Access Point) can’t put the overdose medications in place, the wound care and the mental health and all of those things. Nobody’s saying that. They’re just saying they’re tired of the needles.”

That echoed the concerns of citizens in support of the ban. Local business owner Sam Hernandez said he felt the exchange was enabling drug use in the community, with residents — particularly children — suffering the consequences.

“My son plays tee ball, we’ve got to watch for needles when they go to tee ball practice, soccer practice,” Hernandez said. “When are we going to stop thinking about these grown adults making poor decisions and think about the next generation.”

In a Facebook post, Access Point said the organization is “willing to work together to seek solutions that are based on best-practices and not driven by fear and stigma against some of the state’s most marginalized citizens.”

The organization operated its exchange as normal Tuesday, as it awaited the ordinance’s approval from Pueblo Mayor Heather Graham.

The Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment’s list of syringe access programs that remain in the state includes Denver, Boulder, Colorado Springs and Grand Junction.